Last week, I discussed the Coercive Acts that Lord North and Parliament decided would finally cow the colonists into submission and show them who was boss. This week, we’ll take a look at how that worked in practice.

Gen. Gage replaces Hutchinson

While Lord North passed the Coercive Acts in the spring of 1774, he knew he would need a strong hand in the colonies to enforce them. He decided to replace Gov. Hutchinson. Gen. Gage, the military commander of North America, would be the new Governor of Massachusetts..

I have discussed Gage’s exploits in America in previous episodes and gave a background on him back in Episode 19 when he became succeeded Gen. Amherst as Military Commander of North America. But now might be a good time for a refresher. The second son of an English Viscount, Gage joined the army at age 20 to fight in the War of Austrian Succession. He came to North America with Gen. Braddock in 1754. In 1758, he found time to marry a Jersey Girl, Margaret Kemble, and start a family in America. He continued to serve throughout the French and Indian War, fighting under General Amherst when he defeated the French in Canada in 1760. He then became the military governor of Montreal. When Amherst returned to England in 1763, Gage became the North American Commander, just in time to clean up the mess of Pontiac’s Rebellion. He spent the next decade as Commander, much of it living in New York City.

|

| London Political Cartoon, 1774 showing Lord North forcing the Coercive Acts down the throat of America. (from Library of Congress) |

Gage supported the Coercive Acts and had even suggested similar measures in a letter to London four years earlier. He seemed like just the man to return to the colonies and bring order to Massachusetts. Lord North summoned him for discussion and decided he should return as the Governor of Massachusetts where his strong leadership and military bearing would force the colonists to accept the new laws.

Despite years as a military Governor in Canada, Gage would not really be described as a politician or diplomat. He was a military officer who obeyed orders from superiors and expected obedience from his subordinates. Of course, that is what officials London wanted - someone who would stand up to the locals and intimidate them into submission.

Gage left for Massachusetts in April 1774, just days after passage of the Port Act, and while debate on the Government Act and the Justice Act, or “Murder Act” as it would become known in the colonies, was still under debate. Gage knew a fight was coming. His job was to prepare to suppress any resistance, by fear and intimidation if possible, or with guns if necessary. He arrived in Boston on May 13, with news of the Port Act's closure of the Port of Boston and the unhappy news for Gov. Hutchinson that he was out of a job.

Gage told Hutchinson that his appointment as Governor was temporary, just until the colony calmed down and accepted British authority. After that, Hutchinson might return. The Ministry still approved of Hutchinson, but didn’t think he had the military bearing and forceful will to handle what was coming next. I think Michael Corleone expressed the sentiment best: “You're not a wartime consigliere, Tom. Things may get rough with the move we're trying… You’re Out Tom.”

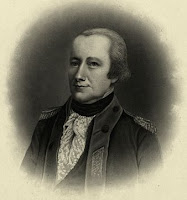

|

| Thomas Gage (from Wikimedia) |

There was no need to remove Lt. Gov. Oliver. He had died suddenly from an illness in March 1774. To give you some idea of how bitter things had gotten, the Sons of Liberty cheered at his burial.

The people of Boston seemed to welcome Gen. Gage at first. It was not the first time a military commander had served as their Governor. Gov. Shirley had also served as Commander in Chief of North America. They were so ready to be done with Gov. Hutchinson that they thought anyone would be an improvement. But as they would say in Massachusetts, the honeymoon period was wicked short.

Despite the cordial greeting, Gov. Gage immediately set about preparing to bring order to Massachusetts. In preparation for closing the Port of Boston on June 1, only two weeks after his arrival, he moved the Customs Office to Plymouth and the seat of government to Salem.

No Compromise

I mentioned a couple of episodes back that following the destruction of the tea in Boston, anti-tea hysteria struck most of the colonies, leading to even more destruction of tea and a complete boycott of all tea consumption. Bostonians had even tarred and feathered another customs official in January. The Tea party had ramped up radical zeal.

At the same time though, there were a number of moderate patriots, men like John Dickinson or George Washington who thought the destruction of the tea had gone too far. Washington commented on hearing of the events that he thought the Bostonians had gone mad. However, as news of the Port Act and other Coercive Acts arrived, most moderates thought that London had also overreacted to events. Word of the changes to the Massachusetts Charter and the military occupation of Boston made clear that everyone had to pick a side. This pushed a great many moderate leaders into the Patriot camp.

After Gage Arrived in Boston, a group of more than 100 merchants tried to petition him to let them pay off the damages from the destruction of the tea, in order to keep open the port. Merchants were going to lose far more than the £10,000 or so in tea costs than they would from an extended port closure. Some individual merchants offered to put up hundreds, even thousands of pounds individually in order to protect their business.

Gage, however, remained vague on exactly what it would take to reopen the port. He did not want a few loyal merchants paying a ransom to bring things back to normal. He wanted the colony as a whole to repent and show that everyone collectively was willing to repay for the harm and change their ways going forward. With no guarantee that coming up with £10,000 would reopen the Port, the private attempts to avert closure failed.

People instead had to hope that the Boston Town Meeting would look for a compromise solution with London, but that was not going to happen. The Boston Town meeting, headed by Samuel Adams, considered and rejected a proposal to pay any compensation for the destroyed tea. The radicals made clear that anyone looking for a moderate solution would be deemed a collaborator and treated as such. The battle lines were drawn on both sides. There was no room for middle ground.

Solemn League and Covenant

After receiving confirmation in May that Parliament would be closing Boston Harbor, the Boston Committee of Correspondence issued circular letters calling on all the colonies to refuse all trade with Britain until it reopened Boston Harbor. Radicals hoped that such a drastic measure would shock London officials into realizing they had come down too hard on Boston, that the resistance to the Tea tax was an issue that had strong support all across the continent.

The plan, known as the Solemn League and Covanent, the name of which was taken from an agreement between Scotland and England during the English Civil War, received mixed reviews. Some communities supported it strongly. Others had concerns. Banning all imports essentially killed the economy and put whole sectors of colonists out of business. I’m going to discuss the reactions of the other colonies to this in more detail in a few minutes. For now, I just want to say that right off the bat, Massachusetts was calling for the mother of all boycotts and asking the entire continent to get on board with the plan.

Gage Closes Boston

Over the summer of 1774, as the colonies talked about doing something, Boston deteriorated. By June 15, the last of the merchant vessels had cleared Boston Harbor. Only British naval vessels enforcing the blockade remained. Local ships carrying food and fuel to Boston could still enter, but had to be searched at a neighboring port prior to entry.

Gage enforced the restrictions with a ruthless zeal. He did not even allow smaller boats to move internally within the harbor. He required ships carrying food and fuel to Boston to be unloaded completely with all cargo searched thoroughly before being reloaded for final delivery, a costly and time consuming process. His clear goal was to isolate the city of Boston, make its people suffer, bring them to their knees and hold up their capitulation as an example to the rest of the colonies.

|

| London Cartoon, 1774 showing Bostonians suffering from the Port closure. (from Digital History) |

By late June and early July, the British shipped three regiments of soldiers to Boston to occupy the city. These were in addition to the regiment still deployed at Castle William. Several more large ships of the line arrived, with Admiral Samuel Graves replacing Admiral Montegu. Boston now existed under full armed military occupation.

Gage reinforced the defenses around Boston Neck and posted a 24 hour guard there. With the waterways closed, nothing came in or out of Boston without military approval. By August when the Government and Justice Acts took effect, Gage had six regiments of Infantry quartered in Boston, as well as the seventh in Castle William. He also had an artillery unit of 60 soldiers and eight cannon.

As I said, Gage’s strategy, approved if not directed by officials in London, seemed to be to isolate and punish Boston as an example to the rest of Massachusetts and other colonies. This is what happens if you cannot keep law and order. It seems, though, that officials believed what the colonial Governors had been telling them: that all these problems were the work of a bunch of radicals in Boston, the colonists overwhelmingly supported the King and would dutifully fall into line if pressed.

Colonies Unite

Other colonies were not happy about what happened to Boston, but also did not want to see their own colonies shut down, either by order from London or by agreeing to the Solemn League to end all trade with Britain.

In New York, Radicals Isaac Sears and Alexander McDougall called a meeting of local merchants to discuss their response to the Boston Port Act. Conservatives and moderates flooded the meeting, making sure that the colony did not jump into some radical plan to cut off all trade with Britain. Cutting off the tea trade was one thing. There was plenty of smuggled Dutch tea to replace it. Cutting off all trade would cut off the colony from the necessities of life.

Still, New Yorkers did not want to leave Boston out on its own either. They decided to form a Committee of 51, because it had 51 members on it. The committee headed by a moderate named Isaac Low, included radicals like Sears and McDougall, but it also included conservatives like Benjamin Booth, a recent failed consignee for the East India Company.

|

| Alexander Mcdougall (from Wikimedia) |

Unlike the Massachusetts plan for a Continental Congress that would coordinate opposition to Britain, New York’s idea of a Congress seemed to be a way of putting off any immediate boycotts and give time for tensions to calm. Some conservatives saw it as a way of advising Boston on how to resolve its dispute with Parliament peacefully, and without any further rash behavior.

In Philadelphia, radicals called for a meeting on May 20th. Radicals, Thomas Mifflin, Charles Thomson, and Joseph Reed met with John Dickinson beforehand to get him on board. Dickinson still had strong patriot cred because of his Letters from a Pennsylvania Farmer, that had spurred the Townshend Act protests. He had continue to write some protest articles since then. But Dickinson was a pretty moderate guy who did not want to see any rash action. A continental boycott right away seemed like too much.

Instead, they concocted a plan for the May 20 meeting. Radicals would demand an immediate non-importation agreement, after which, Dickinson would suggest instead calling on the Governor to call the Assembly into session to discuss possible solutions. Coming as an alternative to the immediate non-importation plan, Dickinson’s proposal would seem moderate and get the support of the conservatives. They also agreed to suspend all port activity for one day on June 1, in solidarity with Boston.

Conservatives considered this a victory. They had prevented a non-importation agreement and just called for future meetings. In reality though, the plan got the colonial legislature back in session in time to vote to participate in the Continental Congress and move the colonies farther along toward the ultimate break with Britain.

In Annapolis, the Maryland radicals got control of their meeting on May 25 and agreed to an immediate cessation of all commerce with Britain until repeal of the Port Act. They even added another measure, asking colonial attorneys not to file any suits for debts on behalf of English merchants until Parliament repealed the Port Act. Several other local town meetings agreed to stop imports, including the important port city of Baltimore. They also agreed that a Continental Congress to discuss matters further made sense.

|

| Raleigh Tavern: Williamsburg, VA (from: Wikimedia) |

South Carolina was one of the last colonies to get word of the port closure. The people of Charleston voted to send assistance to Boston: food and money to help the victims, and also agreed to attend the Continental Congress. As I’ve discussed before, South Carolina’s patriot leaning legislature and its royalist governor had been at a standoff for years, unable to pass any legislation at all. South Carolina radicals held an illegal convention in July to select representatives to the Continental Congress. They also created a committee to run colonial affairs in the absence of a functioning legislature. This committee served as the first provisional government in the colonies, operating outside the authority of the governor.

So even before June 1 when the Boston Port closed, most colonies had adopted a response to what they saw as an act of tyranny and despotism. Months earlier, proposals to hold a Continental Congress had been considered radical. At this point, they seemed to be the moderate response by the colonies.

In the end 12 of the 13 colonies agreed to attend the Continental Congress. Only Georgia failed to send delegates. Some saw the convention as a way to unite the colonies in opposition. Others saw it as a way to slow down radical reactions and possibly prevent harmful trade sanctions.

Those who thought that the Congress would cool passions and allow for moderation did not count on the fact that over the summer, even worse news from London would continually arrive. Most first reactions came only after word of the Port Act. When word of the Government Act, Justice Act, Quartering Act, and Quebec act arrived over the summer, colonial tempers only worsened. They also did not count on the violent resistance that Massachusetts would show to the new laws. We will get into more of that in a couple of weeks.

By early September when the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia, the mood for opposition had risen measurably. The Continental Congress would allow colonial leaders to express their dissatisfaction in a more unified way than ever before.

Next week: Virginia Governor Dunmore starts a war with the Indians in an attempt to secure more western lands for his colony.

Next Episode 44: Governing from Salem

Previous Episode 42: The Coercive Acts

Visit the American Revolution Podcast (https://amrev.podbean.com) for free downloads of all podcast episodes.

Further Reading:

Web Sites:

John Malcom tarred and feathered, Jan. 1775: http://common-place.org/book/impressions-of-tar-and-feathers-the-new-american-suit-in-mezzotint-1774-84

Letter from George Washington to George Fairfax, June 1774, discussing Virginia’s response to the Port Act: http://founders.archives.gov/GEWN-02-10-02-0067

Summary View of the Rights of British America, by Thomas Jefferson: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/jeffsumm.asp

Letter from Gov. Gage to Lord Dartmouth, Aug. 27, 1774: http://amarch.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A93419

Free eBooks

(from archive.org unless noted)

Bolton, Charles (ed) Letters of Hugh, Earl Percy, from Boston and New York, 1774-1776, Boston: Charles E. Goodspeed, 1902.

Cushing, Harry (ed) The writings of Samuel Adams, Vol. 3, New York: G.P. Putnum's Sons, 1907.

Dickinson, John An Essay on the Constitutional Power of Great Britain Over the Colonies in America, Philadelphia, 1774.

Erlanger, Steven, The Colonial Worker in Boston, 1775, US Dept. of Labor, 1975.

Ford, Paul L. (ed) The Writings of John Dickinson, Philadelphia: The Historical Society of Philadelphia, 1895.

French, Allen The Siege of Boston, New York: Macmillan, 1911.

Frothingham, Richard History of the Siege of Boston, Boston C.C. Little and J. Brown, 1851.

Frothingham, Richard Life and times of Joseph Warren, Boston:Little, Brown & Co. 1865.

Hoyt, Albert Donations to the people of Boston suffering under the Port Bill 1774-1777, Boston, 1876.

Miller, John Origins of the American Revolution, Stanford, Stanford University Press 1943 (Based on date, I am not sure about the copyright status of this book. Since it may get pulled, I have also included a link to Amazon below).

Quincy, Josiah Memoir of the life of Josiah Quincy, Jun., of Massachusetts, Boston: Cummings, Hilliard & Co. 1825 (written by the son of the subject).

Books Worth Buying

(links to Amazon.com unless otherwise noted)*

Beck, Derek Igniting the American Revolution 1773-1775, Naperville, Ill: Sourcebooks, 2015.

Bunker, Nick An Empire on the Edge, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014.

Carp, Benjamin Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

Knollenberg, Bernhard Growth of the American Revolution 1766-1775, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund 1975.

Labaree, Benjamin W. The Boston Tea Party, Oxford University Press, 1964.

Smith, Page A New Age Now Begins, Vol. 1, New York: McGraw-Hill 1976.

Miller, John Origins of the American Revolution, Stanford, Stanford University Press (1943) (also available as a free eBook, see above).

Raphael, Ray & Marie The Spirit of ‘74: How the American Revolution Began, New York: The New Press, 2015.

Unger, Harlow American Tempest: How the Boston Tea Party Sparked a Revolution, Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 2011.

* (Book links to Amazon.com are for convenience. They are not an endorsement of Amazon, nor does this site receive any compensation for any links).

No comments:

Post a Comment