We last left Nathanael Greene‘s, southern army at the battle of Guilford Courthouse in North Carolina in March 1781. After that battle, Greene had to decide what to do next. Although he technically lost the battle by withdrawing from the field, he had inflicted a grievous wound on General Cornwallis’ British army by taking so many British casualties.

General Cornwallis retreated eastward with his army to Wilmington, North Carolina. At first Greene shadowed Cornwallis. But as the British army got closer to the coast, Greene knew he was not going to pick a fight where the army had backup from the British Navy. He would only fight the British on ground that he chose.The North Carolina militia that was with Greene would see its enlistments end at the end of March. The men needed to get home and begin their planting season and were not inclined to stick with Greene. With that, Greene’s army shrank back mostly to its core of Continentals.

Greene decided to leave North Carolina again, this time moving southward to South Carolina. If he could get Cornwallis to follow him, he could draw the British out of North Carolina and back further south. That would be a strategic victory for the Continentals. If Cornwallis did not follow, Greene could pick off the British and loyalist outposts in the backcountry of South Carolina and Georgia.

In many ways, Greene’s decision to move south violated good military practice. He knew that forces were gathering in Virginia, and that by moving away from those armies, he was once again dividing Continental forces in the face of a larger enemy that was concentrating its army, for an obvious attack. Green also risked that Cornwallis would chase after him and attack him in his rear while he was focused on other targets.

Greene’s second in command, the Baron Von Steuben said as much in letters to Greene. Von Steuben hoped that Greene would provide him with some assistance in Virginia against the growing army under General William Phillips. Instead, Greene was running in the other direction. When Von Steuben asked Greene in letters about why he was headed away from the enemy. Greene responded in a letter. “don’t be surprised if my movements don’t correspond with your Ideas of military propriety. War is an intricate business and people are often [saved] by ways and means they least look for or expect.”

Green went on to explain in his letter that because his march southward made no military sense that it would confuse general Cornwallis. Perhaps it would make the enemy think that he had some secret reason for doing what he was doing. But, of course, he really didn’t have any secret reasons. He was just trying to confuse the enemy by violating some basic precepts of good military strategy.

Fort Watson

In South Carolina, the British still had thousands of soldiers. Most of them, however, were stationed around Charleston. They maintained several outposts to assert control of the entire state. One of the largest was at Camden, where the British defeated the Continentals a year earlier. If Greene could take Camden, it would be seen as a major victory.

In order to isolate and weaken Camden, Greene first tried to cut off the supply lines between Camden and Charleston. He gave that mission to his cavalry commander, Colonel Light Horse Harry Lee. He told Lee to link up with Colonel Francis Marion’s local militia.

The British had built a small fort along the Santee River between Camden and Charleston to facilitate supply lines. Fort Watson got its name from the British officer who ordered its construction: Lieutenant Colonel John Tadwell Watson. British Lieutenant James McKay commanded a garrison of 114 regulars and loyalists. Given the number of patriot raids in the region, it was designed to withstand a sizable attack. The defenders had set the fort on high ground, with a wall surrounded by three rows of abatis. They had cut down all trees within rifle range in order to deny cover to any attackers.

General Thomas Sumter had attacked the fort in February, but without success. However the attack caused Colonel Watson to pursue Sumter, which is why Lieutenant McKay commanded the fort with a reduced garrison.

Lee and Marion targeted the fort. Taking it would not only isolate Camden from Charleston. The attackers also wanted the food and ammunition stored at the fort. Lee had about 300 men under his command. Marion had another 80. The combined forces approached the fort on April 15, 1781 and demanded its surrender.

Although the British garrison was outnumbered nearly four to one, McKay was confident of his defenses and refused to surrender. Given the defenses, the attackers hoped to avoid a frontal attack and had no artillery to assault the fort. Instead, they settled in for a siege.

At the outset, things did not look good for the attackers. They tried to cut off the fort’s access to water, but the garrison had a well within the fort walls. Marion’s militia also faced an outbreak of smallpox, although fortunately the Continentals under Lee were inoculated. If the siege went on too long, a relief force from Charleston might chase off the Americans.

After about a week, the Americans decided on a new plan. The fort was built on a mound of about 22 feet. On that was a seven foot wall. The attackers needed a way to get over that wall.

|

| Maham Tower at Ft. Watson |

The men dragged out their parts and assembled the fort overnight on April 22. The tower stood over forty feet tall and allowed riflemen to fire through loopholes cut into wooden defenses that were built into the tower. The riflemen had a clear shot over the wall at anyone inside the fort.

The next morning several riflemen climbed into the tower, supported by a larger detachment of soldiers behind man-made defenses at its base.

The British fired on the tower, killing two Americans. Inside the fort, several men were hit, including Lieutenant McKay, who was wounded. The riflemen in the tower forced everyone in the fort to take cover, meaning they could not provide much defensive fire. The attackers used this opportunity to disassemble the abatis and prepare for an all out attack on the fort walls.

Lieutenant McKay, seeing preparations for a final assault, surrendered the fort and its garrison. The Americans captured the fort supplies, and then destroyed the fort. Under the terms of the surrender, the Americans allowed the surrendering officers to keep their swords and baggage, and return to Charleston under parole. The enlisted regulars, about two-thirds of those captured, were also permitted to return to Charleston and await exchange. The thirty-six loyalists, however, were taken as prisoners.

All of the supplies in the fort went to Lee’s Continentals, except for the ammunition, which Marion’s men desperately needed to continue to fight. After removing the supplies from the fort, Marion ordered it burned so that the British could not come back and occupy it again after they left.

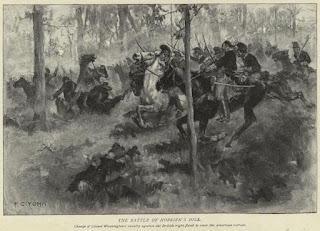

Hobkirk Hill

Even before the Siege at Fort Watson had ended, General Greene moved his main army closer to Camden in hopes of taking that outpost. Rather than a direct attack, Greene set up a defensive position just north of Camden at a place known as Hobkirk Hill.

Camden, at the time, was only a small village of twenty one houses. But the British had built defenses all around the town that would make any direct attack costly. There were eight earthen redoubts, surrounded by ditches and abatis.

|

| Nathanael Greene |

Hobkirk Hill offered the Americans the high ground. The position gave them a good view of an approaching enemy with a forest on one side and a swamp on the other, thus preventing a surprise attack on their flanks.

On the night of April 24, an American deserter entered the British lines at Camden. He told the commander, Lieutenant Colonel Francis Rawdon, that Greene was still awaiting reinforcements and that he did not yet have his artillery. If the British launched a surprise attack, they could be victorious.

Lord Rawdon was only twenty six years old at the time, but was an experienced officer. He had been fighting in the Revolution since he had led his regiment at Bunker Hill, six years earlier. Cornwallis had left Rawdon in full command of the South Carolina frontier, which included pretty much everything outside of the greater Charleston area.

Rawdon figured that an attack would be his best opportunity, and prepared to march out to the enemy the following morning. If Greene did not have his artillery yet, and could link up with Lee and Marion after a few days, attacking now was Rawdon’s best option.

At around 9:00 on the morning of April 25, Rawdon marched out of Camden with 900 soldiers. These included several regiments of regulars, several provincial regiments with considerable battlefield experience, and two field cannon. He did not know that Greene’s force was considerably larger than his, and did have its artillery in place.

Greene had sent some of his artillery away, after hearing a rumor that reinforcements were on their way to Camden to support Rawdon. But when those rumors proved false, the artillery returned to Hobkirk Hill, and was in place by the morning of the battle. At around 11:00 the British column ran into the American pickets, Delaware Continentals under the command of Captain Robert Kirkwood. The skirmishing that took place gave the Americans time to form up their lines on the hill.

Two Maryland regiments, under the overall command of Colonel Otho Holland Williams, made up the American left flank. Two Virginia Regiments under General Isaac Huger made up the right flank. The British came through the woods, formed ranks and began a slow advance toward the Americans.

|

| Hobkirk Hill |

Even so, Rawdon had only about 900 soldiers against nearly 1500 under Greene. As the two lines advanced, things began to break down.

On the left flank, after Captain William Beaty was shot dead, the Maryland line began to collapse. The regiment’s Colonel John Gunby ordered his men to pull back and reform. But his second in command did not get the orders and continued to advance with only part of the regiment. The other Maryland regiment’s commander, Colonel Benjamin Ford, also fell leading to even more confusion.

On the right flank the First Virginia Regiment took heavy fire and also pulled back, leaving the Second Virginia to take the full brunt of the British advance.

Green had sent his cavalry under William Washington on a long ride to get around the British rear and attack them from behind. But before Washington could get to the battlefield, it was over.

With his lines descending into chaos, Greene ordered a retreat and abandoned Hobkirk Hill.

Despite the battlefield confusion, the lines managed to withdraw without collapsing in a panicked run. Greene was even able to withdraw his cannons, although he personally had to get off his horse and help push the cannons off the field.

The Americans fell back about six miles. The British did not pursue. Rawdon was already out numbered. He did not want to get too far from his base at Camden, especially if the Americans might soon receive reinforcements. Rawdon pulled back to Camden.

The fight had been a brutal one. The British lost over 200 killed and wounded, and another 50 captured. The Americans took 270 casualties, about half of those being captured. Among the prisoners captured by the Americans were perhaps two dozen who were believed to be American deserters. Greene held court martials and hanged at least five of them

Following the battle Greene was depressed. He outnumbered the enemy, even without having to rely on militia, and still lost the battle. He blamed his field officers for the loss, particularly Colonel Gunby. He even called a court in inquiry into Gunby’s actions during the battle. Greene also expressed a concern to other officers that they might be pushed back into the mountains and have to cede South Carolina to the British, even without Cornwallis to defend the state.

A few days later though, his mood brightened. Lord Rawdon, following the bloody battle, and after hearing about the fall of Fort Watson, decided that his outpost at Camden was too much of a risk. On May 10, the British evacuated Camden and marched back to Charleston.

Fort Motte

Even before the British withdrew from Camden, Greene continued his efforts to take out smaller British outposts wherever possible. Following the fall of Fort Watson, Green ordered Lee and Marion to take Fort Motte, a supply depot on the Congaree River.

Although Lee and Marion had fought well together at Fort Watson, there were divisions between Marion’s militia and the Continentals. One flash point at this time was over horses. Marion had been confiscating horses from locals that he believed to be loyalists. It was how he kept his militia mounted and on the move. Greene, who was trying to improve public opinion toward the patriots, told Marion to stop doing this.

|

| Mrs. Motte directs officers to burn Fort Motte |

Fort Motte was set on a plantation. Its owner was a widow named Rebecca Brewton Motte. Her husband, Jabo Motte had fought for the patriots at Fort Moultrie in 1776, but had died of an illness in 1780. The British took over the plantation in early 1781, allowing Rebecca and her family to reside in an old farmhouse.

The Motte plantation proved to be in a valuable position, near McCord’s Ferry, and along a route used to ship supplies from Charleston to Camden. The British garrisoned the plantation with 80 regulars, 59 Hessians, and 45 loyalist militia, along with a single field cannon. Command fell to British Lieutenant Donald McPherson. The garrison occupied the plantation’s mansion, which sat at the top of a hill. They build defenses, including abatis, a ditch, several palisades and a wooden parapet, along with two block houses to cover the flanks. It was used primarily as a supply depot for goods shipped to the British garrison at Camden.

Before the British evacuated Camden, Greene viewed the capture of Fort Motte as yet another way to isolate the Camden outpost. Lee’s legion, along with Marion’s militia, arrived at Fort Motte on May 7.

Fearing that frontal assault against the defenses would prove too costly, Lee opted for a siege. He had a single field cannon, which he positioned to fire at the mansion. He then used his soldiers, supplemented by local slaves, to dig a zig zag trench toward the enemy lines.

|

| Lord Rawdon |

By May 10, the trenches were complete. Lee called for Lieutenant McPherson to surrender the fort. Although heavily outnumbered, McPherson still hoped that a relief force from Camden would come to his rescue. Although Lord Rawdon evacuated Camden that night, his army would march past Fort Motte on its way to Charleston and could relieve the garrison.

On the night of May 11, both the attackers and defenders saw British campfires in the distance, and anticipated the relief force would arrive within two days.

Lee decided the only way to win would be to set the mansion on fire and burn the fort. He obtained Mrs. Motte’s consent to burn the home. According to some accounts, he used flaming arrows. Other evidence suggests the men fired ramrods with combustibles attached onto the wooden roof.

British soldiers scrambled onto the roof to douse the fires, but Lee fired grapeshot from his cannon to keep them away. With the house now on fire, McPherson surrendered the fort. Both sides then struggled to put out the fire and save the mansion.

The British garrison was taken prisoner, and the Americans managed to capture a canon, 140 muskets, and a great many supplies being held at the depot.

Following the fort’s surrender, another fight erupted. General Greene arrived at Fort Motte just after the British surrender, and just in time to enjoy a dinner with the officers of both sides in the dining room of the widow Motte’s farmhouse. It was the first time Greene and Marion had met in person. Also at the table was British Lieutenant McPherson, and several other captured officers who were now American prisoners.

As the officers enjoyed a dinner together, one of Lee’s officers, allegedly on Lee’s orders, hanged three of the captured loyalists. These were men identified by the Americans as having burned patriot houses in earlier actions.

Upon hearing the news, Marion dashed out of the house to find two of the loyalists already dead, and a third dangling from a noose slowly suffocating. He cut down the man and told the Continentals that he would personally kill any man who tried to hang any more of his prisoners.

Civil Authority

Tensions between militia and Continentals was nothing new. While Greene struggled to smooth over their differences, he had other concerns. With Rawdon’s evacuation of Camden and the fall of key outposts, the patriots were re-asserting control of South Carolina.

Greene wrote to Governor John Rutledge, by this time in Philadelphia, to urge him to return to South Carolina and restore civil authority. With British forces bottled up around Charleston, Greene wanted to establish that the rest of South Carolina was once again under patriot control.

Next week: we continue the battle for South Carolina as the fights continue over the last of the British outposts along the frontier.

- - -

Previous Episode 284 Pensacola

|

| Click here to donate |

|

| Click here to see my Patreon Page |

An alternative to Patreon is SubscribeStar. For anyone who has problems with Patreon, you can get the same benefits by subscribing at SubscribeStar.

| Help Support this podcast on "BuyMeACoffee.com" |

Signup for the AmRev Podcast Mail List

Further Reading

Websites

Free eBooks

(from archive.org unless noted)

Books Worth Buying

(links to Amazon.com unless otherwise noted)*

Carbone, Gerald Nathanael Greene: A Biography of the American Revolution, St. Martin’s Griffin, 2010 (borrow on Archive.org).

Ferling, John Winning Independence: The Decisive Years of the Revolutionary War, 1778-1781, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021.

Golway, Terry Washington's General : Nathanael Greene and the triumph of the American Revolution, H. Holt, 2006. (borrow on Archive.org)

Lumpkin, Henry From Savannah to Yorktown: the American Revolution in the South, Univ of SC Press, 1981 (borrow on archive.org).

Murphy, Daniel William Washington, American Light Dragoon: A Continental Cavalry Leader in the War of Independence, Westholme Publishing, 2014.

Nelson, Paul D. Francis Rawdon-Hastings, Marquess of Hastings, Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press, 2005.

Tonsetic, Robert L. 1781: The Decisive Year of the Revolutionary War, Casemate, 2011 (borrow on archive.org).

* As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

No comments:

Post a Comment