The British southern command had burst into new activity beginning with the capture of Savannah, Georgia in December, 1778. After Colonel Archibald Campbell captured Savannah, General Augustine Prévost marched a larger force up from St. Augustine Florida to occupy the area around Savannah.

The British offensive began just as American General Robert Howe was turning over command to General Benjamin Lincoln. General Lincoln had only reached Charleston by the time the British attacked Savannah. Lincoln then moved to the Georgia-South Carolina border to confront the enemy. This led to a stand off, and kept the British penned up in and around Savannah. That is where I left things a few weeks ago in Episode 208. In the following weeks and months, the British attempted to expand on their victory at Savannah and the Americans tried to stop them.

Battle of Beaufort

Eager to maintain the offensive, General Prévost ordered an attack on Port Royal, South Carolina, about forty miles from Savannah. This, he hoped, would be the beginning of a British toe-hold in a second rebellious colony. He also hoped the action would distract the Americans under General Lincoln from the British occupation of Georgia and get the Continentals to deploy more of their forces to the South Carolina coast.

|

| William Moultrie |

Port Royal was an island on the coast, meaning it would be more easily defensible, and could be backed up by the British Navy if needed. Local intelligence also indicated that there were many loyalists in the area who would support the British liberation of the region.

The British at Savannah had a ship, the Vigilant. This was a smaller 6th rate ship with about 20 cannons on it. The ship had been damaged months earlier in the same storm that dispersed the French and British fleets off of Newport, Rhode Island. By the time the Vigilant reached Savannah, Georgia, it was deemed “unseaworthy” and incapable of sailing on its own. It was still capable of floating and housing its artillery. The British towed the ship to the waters off Port Royal Island to serve as a floating battery to back up the soldiers as they landed on shore.

Aboard several smaller ships, about 200 regulars under the command of Major William Gardner moved set sail for Port Royal in late January. However, since they had to tow the Vigilant with rowed longboats, the move took several days.

The island’s defenses consisted of a small defensive area at the town of Beaufort, known as Fort Lyttelton. There were a few dozen Continentals at the fort under the command of Captain John DeTreville. When Captain DeTreville learned of the approaching British, he knew he could not withstand an assault or siege. In order to avoid capture and deny the fort to the enemy, Captain DeTreville spiked the fort’s cannons and blew up the main bastion. He then evacuated his men back to the mainland before the British arrived on the island.

General Lincoln, however, did not want to cede any South Carolina territory to the enemy. By the time the British landed on Port Royal, Lincoln had already dispatched a 300 man force under the command of Continental General William Moultrie, the same officer who had defended Fort Sullivan in Charleston Harbor back in 1776. Most of the men under Moultrie were South Carolina militia, who Moultrie himself noted, were ill-trained and ill-disciplined. A few Continental soldiers accompanied the brigade, as did two local artillery companies from Charleston, headed by former Congressmen Edward Rutledge and Thomas Heyward. Moultrie’s force crossed onto the other end of the island on February 1, a day before the British landing.

|

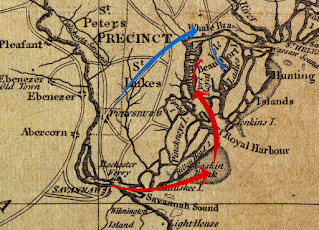

| Beaufort, Troop Movements |

The two forces met near the middle of the island. Major Gardner advanced to the top of a hill and had his men fix bayonets inside a tree line. General Moultrie formed his men in a line in a nearby field, in sight of the enemy. To supplement his lines, he deployed his two six-pound field cannon in the middle of his line and a smaller two-pound cannon on the right flank. General Moultrie noted later that the armies reversed their usual operations, with the Americans out in the open field and the British using the forest as cover.

The Americans outnumbered the British and also had the advantage of field artillery, while the British had none. The Americans opened fire, but were out of musket range and did little damage. After about 45 minutes, the Americans were beginning to run low on ammunition. Moultrie began preparations to withdraw when he realized that the British were also beginning to withdraw.

Major Gardner opted not to charge a superior force with cannon and decided to march back to the coast where the British would have the cover of the cannons from the Vigilant. Seeing the retreat, Moultrie ordered a company of militia cavalry to cut off the British. The cavalry managed to get behind the British retreat and captured a wounded captain and 25 other enemy soldiers. However, there were not enough cavalry to contain them. The prisoners made a break for it, with about half of them escaping back to the British lines.

The British had taken substantial casualties from the American artillery, reporting at least 40 killed or wounded. The Americans reported 7 killed and 18 wounded.

The Americans declared victory for the battle, as the British had retreated back to their boats and returned to Savannah. British regulars rarely backed down against militia, even if the militia has superior numbers. After the return to Savannah, General Prévost criticized Gardner for moving his troops too far in advance of the ships and the protection of the cannons. The men had to fight their way back to the ships in some of the bloodiest fighting of the day. But if the Americans had failed to bring up artillery, the battle might have gone very differently.

So, by the second week of February, the British found themselves back in Savannah and still facing the danger from General Lincoln’s forces only a few miles away in Purrysburg.

Kettle Creek

Recall that Colonel Archibald Campbell had captured Savannah in late December, 1778. He then turned over command to General Augustine Prévost in January, 1779, after Prévost marched an army up from St. Augustine, Florida. After that, Campbell took an expedition up to take control of Augusta at the end of January, about the same time Major Gardner was moving to take Port Royal.

|

| Kettle Creek |

In taking Augusta, the British saw the local militia flee the town with no real resistance. Colonel Archibald Campbell then began taking loyalty oaths and trying to establish loyalist militia in the backcountry in order to secure Georgia and with plans to take an invasion force into South Carolina.

To assist in recruitment, Campbell had brought with him a prominent colonist from the Carolinas named John Boyd. As a loyalist, Boyd had made his way to British occupied New York where he assured General Clinton that he could raise a loyalist army in the Carolina backcountry if Clinton could get some regulars down there for the men to rally around. Boyd received a militia commission as a lieutenant colonel and joined Colonel Campbell for the invasion of Savannah. Boyd then made his way through the Carolina backcountry, recruiting his loyalist army, well into North Carolina.

These were the same Scotch-Irish Loyalists who had risen up to support the British when they first tried to land at Cape Fear in 1776. The patriots had decimated and scattered them at Moore’s Creek Bridge, something I discussed back in Episode 82. After that, the loyalists had mostly laid low and accepted patriot rule. With the British back in Georgia, this was the opportunity for the loyalists to rise up once again and help the regulars put down this rebellion.

The problem was that the patriots had controlled the Carolinas for three years. The loyalists knew that taking up arms against the patriots would mean that their properties could be confiscated or destroyed. Many of those who did join Boyd saw their homes burned while they were away. These volunteers could also be hanged as traitors to the state. Many of the more prominent loyalists took the safest option and did not join Colonel Boyd. They stayed on their plantations and remained neutral.

While recruiting was not as fruitful as hoped, Boyd did manage to recruit several hundred men in North Carolina, and then added to his recruits as his new loyalist militia army marched south to join with the British at Augusta. As Boyd approached Augusta, his army had reached somewhere between 600-800 men.

|

| Andrew Pickens |

Campbell had deployed Captain John Hamilton with about 300 Tories to secure various outposts around Augusta. He divided his forces to take control of more area. Pickens’ patriots came after Hamilton who had about 100 men with him at the time. The loyalists took refuge in a small redoubt known as Carr’s Fort. There, the Americans began a siege, hoping to capture the loyalists before Campbell could send out a relief force from Augusta.

Just as the siege was getting started, Pickens received word that Boyd’s loyalist army was in the area, and trying to get to Augusta. Pickens gave up on the smaller force in hopes of intercepting Boyd’s militia.

The loyalists under Boyd were still in South Carolina, near the Georgia border. On February 11, they approached an area known as Vann’s Creek, where a patriot blockhouse guarded the ford. There were only eight patriots guarding the ford when confronted by up to 800 loyalists. However, the patriots had a defensive wall backed by two swivel guns. They opened fire on the loyalists. Another 40 patriots quickly crossed the river in canoes, to supplement the defense.

Boyd was not looking for an encounter at this time. It is possible that many of his men did not even have arms, something they would receive when they reached Augusta. There is also some evidence that many of the loyalists under Boyd’s command had come under pressure to do so and were looking for an opportunity to desert.

As a result, Boyd opted to avoid having to storm the blockhouse and moved his men to a point about ten miles upstream where they could cross unimpeded into Georgia. After that, Colonel Boyd rested easy. He was inside British lines and only a few miles from a loyalist militia camp. Boyd awaited word from Augusta about connecting his militia with the British regulars there. His army set up camp to rest from its long march near a small stream known as Kettle Creek.

Boyd had not heard that Campbell had decided to abandon Augusta and had put his men on the march back to Savannah. His camp was more isolated than he knew. The patriots under Pickens had not given up the chase. Pickens marched his patriot militia back across the Savannah River into Georgia.

On the morning of February 14, Pickens divided his patriots into three columns and attacked the Loyalist camp under Boyd. The loyalists probably had close to twice as many men as the attacking patriots. But they were taken by surprise. Boyd had failed to put out sufficient pickets or patrols to keep watch for any enemy. As I said, it is also possible that many of the loyalists still did not have muskets.Boyd quickly organized a defensive barrier where he and about one hundred of his men confronted the attackers, while the bulk of the patriots moved to higher ground in their rear. The defense was fairly effective, with the battle raging for more than 90 minutes. Eventually, the larger patriot force managed to outflank the loyalist line and force the defenders to retreat back to the main British line to the rear. During the retreat, Colonel Boyd received a mortal wound and would die later that evening.

The patriots continued their assault, up the heights against the main loyalist force. Boyd’s second in command, Lieutenant Colonel John Moore was also killed or wounded. Third in command, Major William Albertus Spurgeon Jr., attempted to rally the loyalists but failed. The terrified loyalists broke and ran, leaving behind their horses, supplies and tents, fleeing into the swamps. The patriots overran their lines in a complete route.

The loyalists suffered between 40 and 70 killed, another 75 or so were captured, many of whom were also wounded. Most significantly, many of the loyalists used the opportunity to flee and return home. Some of these men surrendered later while trying to get away. As a result, only 270 loyalists made it to Augusta, far less than half of those recruited. The patriots suffered only 7-9 killed and 14-23 wounded or missing. They also managed to free 33 patriots who the loyalists had taken prisoner during their march from North Carolina.

Trials

The loyalists who became prisoners at Kettle Creek had to suffer the wrath of their patriot neighbors. Even before the battle, North Carolina patriots reported burning the homes of many of the men who had left with Colonel Boyd’s army. Those taken prisoner were not treated as prisoners of war. Rather, they were prosecuted as criminals who had committed treason by taking up arms against the state government. These men had also incurred the wrath of locals by looting and pillaging homes during their march from North Carolina to Georgia.

At first, Colonel Pickens occupied Augusta following the British withdrawal. He took about 75 prisoners captured at Kettle Creek and put them under guard in Augusta. He also put out the word that any other loyalists who had escaped Kettle Creek should turn themselves in. They would have to post bond and then would be released. Another 75 or so loyalists took advantage of this offer and turned themselves in. It turned out though, that the offer was a lie. Pickens threw these men into the prison with the men who had been captured on the battlefield.

|

| Fort 96 Stockade |

The prisoners arrived on March 10. The trials had been scheduled to begin the day before, but had been postponed. The trials finally began on March 22. It took about three weeks to try all the prisoners, which were concluded by April 12. There are no surviving records of the trial, but we know the prisoners’ fates were decided by a jury selected by the local Sheriff, William Moore.

Of the 150 or so prisoners, roughly half of them were released without being found guilty. Since there are no court records, it is not clear why. Another 50 or so prisoners were found guilty of treason, but were granted reprieves. Many of the prisoners had argued that they had been forced into joining Boyd’s army either by pretense or threats. For whatever reason, only twenty-two of the men received death sentences. The court scheduled the hanging for April 17. According to one of the condemned prisoners, the gallows were constructed in the site of the jail

Five of the prisoners Charles Draper, John Anderson, James Lindley, Samuel Clegg, and Aquilla Hall went to the gallows that morning and were hanged. We don’t have details on all the condemned men, but for those for whom we do have details, it appears that those condemned had held positions of prominence in the colonies before the war, and may have served officers under Colonel Boyd. Clegg, for example, had served as a tax collector in South Carolina and had served in the colonial assembly. Hall had been a wealthy plantation owner and had actively recruited for Colonel Boyd. Lindley had served as a justice of the peace in North Carolina, and had been a captain in the provincial militia. He had also been captured and released by the patriots on one prior occasion.

After the hanging of the first five men, a message arrived from Governor Rutledge of South Carolina with a writ of habeas corpus ordering the condemned men to be moved to Orangeburg. The remaining 17 condemned prisoners escaped the hangman’s noose and were sent off as prisoners. The reprieve may have been the result of British threats to begin hanging American prisoners in retaliation. In any event none of the other 17 men were ever executed and eventually were exchanged or released.

I’ll get into those details more next week, when we cover the continuing fighting between Georgia and South Carolina at the Battle of Brier Creek.

- - -

|

| Click here to donate |

|

| Click here to see my Patreon Page |

An alternative to Patreon is SubscribeStar. For anyone who has problems with Patreon, you can get the same benefits by subscribing at SubscribeStar.

| Help Support this podcast on "BuyMeACoffee.com" |

Signup for the AmRev Podcast Mail List

Further reading

Websites

Encounter at Vann’s Creek (archived brochure): https://web.archive.org/web/20170211081717/http://gassar.org/revtrail/pdf/brochure_vannscreek.pdf

Battle of Kettle Creek: https://kettlecreekbattlefield.com/the-battle-of-kettle-creek

Battle of Kettle Creek https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/kettle-creek

Henry, William An Unfortunate Affair: The Battle of Brier Creek and the Aftermath in Georgia, Georgia Southern University, 2021: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1914&context=etd

Chained and Tried: The Fate of the Loyalist Prisoners from Kettle Creek https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/chained-and-tried-fate-loyalist-prisoners-kettle-creek

Davis, Robert Scott. “The Loyalist Trials at Ninety Six in 1779.” The South Carolina Historical Magazine, vol. 80, no. 2, 1979, pp. 172–181. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27567552

Zachariah Gibbs http://sc_tories.tripod.com/zachariah_gibbs.htm

John Ashe: https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/ashe-john

General John Ashe: https://ashefamily.info/people/born-in-the-18th-century/major-general-john-ashe-1720-1781

Andrew Williamson: https://www.carolana.com/SC/Revolution/patriot_leaders_sc_andrew_williamson.html

Ashmore, Otis, and Charles H. Olmstead. “The Battles of Kettle Creek and Brier Creek” The Georgia Historical Quarterly, vol. 10, no. 2, 1926, pp. 85–125. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40575848

Heidler, David S. “The American Defeat at Briar Creek, 3 March 1779.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly, vol. 66, no. 3, 1982, pp. 317–331. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40580932

Cox, William E. “Brigadier-General John Ashe’s Defeat in the Battle of Brier Creek.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly, vol. 57, no. 2, 1973, pp. 295–302. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40579524

Searcy, Martha Condray. “1779: The First Year of the British Occupation of Georgia.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly, vol. 67, no. 2, 1983, pp. 168–188. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40581049

Free eBooks

(from archive.org unless noted)

Jones, Charles C. The History of Georgia Vol. 2, Boston: Houghton & Mifflin Co. 1883:

McCall, Hugh The History of Georgia, containing brief sketches of the most remarkable events up to the present day, (1784), Atlanta: A.H. Caldwell, 1909 reprint.:

Peck, John Mason Lives of Daniel Boone and Benjamin Lincoln, Boston : C.C. Little and J. Brown, 1847.

Books Worth Buying

(links to Amazon.com unless otherwise noted)*

Campbell, Archibald Journal of an expedition against the rebels of Georgia in North America under the orders of Archibald Campbell, Esquire, Lieut. Colol. of His Majesty's 71st Regimt., 1778, Ashantilly Press, 1981.

Cashin, Edward The King's Ranger: Thomas Brown and the American Revolution on the Southern Frontier, New York: Fordham University Press, 1999.

Coleman, Kenneth The American Revolution in Georgia, 1763–1789, Univ. of Ga Press, 1958.

Hall, Leslie, Land and Allegiance in Revolutionary Georgia, Univ. of Ga Press, 2001.

Martin, Scott Savannah 1779: The British Turn South, Osprey Publishing, 2017.

Mattern, David B. Benjamin Lincoln and the American Revolution, Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1998:

Piecuch, Jim Three Peoples, One King: Loyalists, Indians, and Slaves in the Revolutionary South, 1775-1782, Columbia: Univ. of South Carolina Press, 2008.

Russell, David Lee. The American Revolution in the Southern Colonies. McFarland & Company, 2000.

Wilson, David K. The Southern Strategy: Britain’s Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia 1775-1780, Univ. of S.C. Press, 2005.

* As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

No comments:

Post a Comment