Last week, I went over the extensive Delaware River defenses that continued to keep the British Army in Philadelphia from being able to connect with the British Navy still further downriver. Without control of the river, and with the Continentals cutting off access to food and supplies from the countryside, the British faced the possible danger of being starved out. As such, opening the Delaware River became a top priority.

|

| Fort Mifflin (Wikimedia) |

After the British took Fort Billingsport without much of a fight, as I discussed last week, the only real barrier between the navy and Philadelphia was Fort Mercer on the New Jersey side of the river, and Fort Mifflin, on an island just off the Pennsylvania side. Between the two forts, the Americans had placed several rows of underwater chevaux de frise, which as I explained last week, were really large pointy sticks, with metal tips and attached to the bottom of the river by boxes of rocks. These prevented any ships from moving upriver without being punctured. The fort cannons on both sides of the river prevented the British from trying to remove these underwater blockages.

After the Continental attack at Germantown, General Howe spent the next couple of weeks shoring up his land defenses. He pulled his army out of Germantown and moved them behind entrenched lines closer to Philadelphia. Once that was complete, he could turn his focus back to opening the river.

Carl Von Donop

On October 21, 1777 General Howe deployed a division of Hessians under Colonel Carl von Donop to capture Fort Mercer. The colonel swore he would take the fort or die trying.

|

| Carl von Donop (Wikimedia) |

Von Donop had a very traditional, and almost exaggerated attitude to the military command structure. He was always highly deferential and polite to his superiors, and rather short with those beneath him. He had a reputation for having a short temper. He very liberally used floggings to enforce his orders with his soldiers. He even had a standing order in America to take no prisoners. Soldiers under his command who brought back live prisoners could expect to be flogged.

Von Donop had served with distinction during the New York campaign. However, his reputation took a hit at Trenton. Von Donop commanded the outpost near Trenton, which should have been able to support his fellow Hessians on Christmas 1776. Instead, the Americans had lured him farther away from Trenton, down to Mount Holly, in order to isolate the Trenton outpost. After the Continentals captured Trenton, Von Donop had to retreat back toward New York to save his command. On the Philadelphia Campaign Von Donop sought to restore his reputation. His jaeger corps was conspicuously out in front, being as active as possible.

General Howe noticed Von Donop’s efforts and tasked him with the capture of Fort Mercer. This was another opportunity to prove himself. Von Donop crossed into New Jersey with about 2000 Hessians, including three brigades of grenadiers, and four companies of highly-valued jaegers. He also brought several pieces of field artillery to use against the fort.

Christopher Greene

Opposing Von Donop was the fort’s commander, Continental Colonel Christopher Greene of Rhode Island. Colonel Greene was a very distant cousin of General Nathanael Greene. Colonel Greene had entered the war as a major, when he led Rhode Island volunteers to Cambridge in May 1775. He served on Benedict Arnold’s wilderness march to Quebec and led troops under Arnold at the attack on Quebec on December 31.

|

| Col. Greene (Wikimedia) |

Greene commanded about 400 Continental soldiers. This included his regiment and the Second Rhode Island under the command of Colonel Israel Angell, who served as his second in command. Another maybe 200 New Jersey militia were also at Fort Mercer in October. Washington had only deployed the Continentals to Fort Mercer less than two weeks before the battle. Two days after deploying the two regiments, Washington recalled Angell’s regiment for service back in Pennsylvania. Washington then ordered Greene to deploy any members of his garrison with experience aboard ships to join Commodore Hazelwood’s fleet on the Delaware. He also sent orders to send more of his men over to Fort Mifflin, where intelligence indicated the attack might occur.

It was only a few days before the battle that Washington sent back Angell’s regiment to supplement the severely depleted garrison at Fort Mercer. Washington also sent a French officer Thomas Antoine Chevalier de Mauduit du Plessis, who had arrived in America and received a commission as captain of artillery. Du Plessis had engineering experience. Washington hoped he could be of assistance in last minute improvements to fort defenses.

Even with the last minute reinforcements, the defenders of Fort Mercer would be horribly outnumbered by the Hessian attackers. When du Plessis arrived, he immediately recognized that the garrison was far too small to defend a fort that was nearly 350 yards long and 100 yards wide. He suggested that they place the garrison in a small section at the southern end of the fort, and then build a wall between the two sections. Since the fort was made of earthen walls simply dug up and piled high, it was easy enough to create the interior wall.

In the northern section that would be vacated, the garrison built abatis, which are basically pointed sticks placed in such a way to make it difficult to move quickly around the area. The garrison took the Whitall's fruit orchard to make the abatis. The defenders mounted all their cannons in the southern portion of the fort, but kept a few soldiers on the wall in the northern area so that the attackers would not realize that the northern portion had been abandoned.

Battle of Red Bank

On October 22, Hessian Colonel Von Donop organized his troops into two columns totaling about 1200 men. They broke camp before dawn around 3:00 a.m. to make the eight mile march to Fort Mercer. Because the locals had destroyed a bridge to get the fort, the columns had to make a detour and did not arrive until around 1:00 p.m. that afternoon. The Hessians made no attempt at surprise, but began to form lines just outside of rifle shot. They sent a messenger to demand surrender of the fort, which was refused.

|

| Hessians Attack Fort Mercer (Rev War Journal) |

The Hessians struggled to maneuver around the abatis, but could not move easily. Many fell. The few who reached the southern wall found they could not climb it without scaling ladders, which they did not have. Eventually, the survivors pulled back out of the fort.

Von Donop led his second column against the southern part of the fort. His approach also faced cannon and musket fire, as well as fire from American ships on the river. During this assault, Von Donop fell, hit in the leg. The remainder of his attackers withdrew. The entire attack had lasted only about forty minutes. The Hessians later reported a total of 371 casualties. However, American reports indicate the number was closer to 500. Among these, were more than 100 killed outright, and more than 80 captured. Among the captured were twenty Hessians found hiding under the southern wall. They did not want to risk retreating through the killing zone again, when the army withdrew and preferred to be taken prisoner.

|

| Sinking the Augusta (from Carpenter's Hall) |

With most of their officers killed, the surviving Hessians fled into the woods and made their way back toward the ferry to Philadelphia. The New Jersey militia under General Silas Newcomb was in position to run down most of the fleeing Hessians and capture them. However, lacking direct orders from Washington to attack the enemy, Newcomb opted to remain in position and do nothing. Criticism of his lack of action would lead to his resignation just over a month later.

Despite the lack of follow up, Fort Mercer proved a great American victory. The garrison reported only 14 killed and 23 wounded. To complement the Hessian land attack, the British had moved a fleet of five ships up the river to fire on the fort. Commodore Hazelwood sent his naval fleet against the British, combined with cannon fire from Fort Mifflin. The British ships were forced to retreat. One British vessel, the Merlin, ran aground and had to be burned and abandoned. A larger ship of the line, the Augusta, also ran aground but was able to escape after taking severe damage. The following day, fires still burning aboard the Augusta caused the ship to explode, with loss of crew and the abandonment of the ship.

Howe Resigns

The failure to take Fort Mercer made General Howe’s occupation of Philadelphia more tenuous. The British were concerned that if they failed to open up the Delaware before winter set in and the river froze, they could be without sufficient provisions until spring. There was even some discussion of abandoning the city and marching back to New York. The loss also came around the same time as news arrived of General Burgoyne’s surrender at Saratoga.

|

| Gen Howe (Wikimedia) |

Howe knew it would take months to receive a response to his request, and that he needed to take further action to secure Philadelphia for the winter. It was also about this time that Howe ordered General Henry Clinton in New York to send 2000 soldiers to Philadelphia as reinforcements. These orders are what forced Clinton to abandon his gains in the lower Hudson Valley and to return to his defensive posture around New York City.

Fort Mifflin

Since the attempt to capture Fort Mercer had been a bust, Howe focused his attentions on Fort Mifflin. As I said last week, Mifflin was a small fort on Mud Island, just off the coast of Pennsylvania on the Delaware River. It had a rather small garrison, which Washington had increased to about 400 just before the attack on Fort Mercer. Before Washington sent reinforcements in late September, the garrison consisted only of about 60 militia, many of whom were invalids, and none of whom were even trained to fire the artillery at the fort.

|

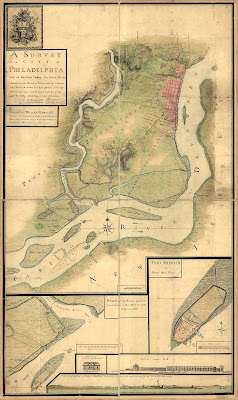

| Forts Mercer, Mifflin & Philadelphia (from Journal of Am. Rev.) |

While surveying the fort for the first time with Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Smith, and a French officer named du Fleury, The men entered a blockhouse that was mostly destroyed. When d’Arendt asked what had happened, Smith told him that the blockhouse was a regular target for the British Navy and that they had blown it up the day before. Upon hearing that d’Arendt fled out of the blockhouse, diving through two windows, which the others took as an act of unnecessary and extreme cowardice. After that, d’Arendt’s illness returned and Lieutenant Colonel Smith assumed practical command of the fort.

On November 9th, General Howe tasked Lieutenant Colonel George Osborn with taking Fort Mifflin for the British. The following day, Osborn’s men occupied Providence Island, just to the north of Mud Island, and installed several large cannons. They also brought a floating battery of cannons, bringing a total of several dozen 24 and 32 pound cannons designed to reduce the fort to rubble. The British unleashed a near continuous bombardment on the fort which lasted for five days. The Americans returned fire, but were vastly outgunned Most of the garrison spent days and nights hunkered down right behind the fort walls. They quickly discovered that moving in the interior of the fort made one a target for the many shells that the British lobbed into the fort’s center.

On the second day, a British shot hit a brick chimney, which collapsed onto Colonel Smith. His injuries required that he be evacuated to Fort Mercer, leaving Major Simeon Thayer in command. The Americans continued to resist the onslaught, taking casualties each day. On November 15, the British Navy brought up several more large ships, and managed to get one of the smaller ones into the shallows between Mud island and the Pennsylvania coast. From there, British cannons could fire almost at point blank into the fort. The Americans lost their large cannon, destroyed by enemy fire. They were also reduced to running through the courtyard to grab British cannonballs to fire back at the enemy.

Commodore Hazelwood attempted to use his Pennsylvania fleet to support Fort Mifflin. However, the British Navy forced him to withdraw.

Osborn had planned to launch an assault that same day, November 15, to capture the fort. However, General Howe declined to approve the attack. On the night of the 15th, the American commander, Thayer, realized that the fort was lost. He moved the surviving garrison across the river in the dark to Fort Mercer. With about 40 men, Thayer then burned what was left of the fort, spiked the cannons, and moved his forces across to Fort Mercer.

On the morning of the 16th Osborn landed on Mud Island to find the fort abandoned. He found only one American deserter who had remained behind and gave him a report of the casualties and the retreat. That man said the garrison has suffered about 50 killed and 70-80 wounded, although other estimates put the total casualty rates closer to 250.

British marines lowered the American flag, which the garrison had left flying, and took possession of the fort ruins. The British reported only 13 dead and 24 wounded.

British Control the River

With the fall of Fort Mifflin, General Howe dispatched General Lord Cornwallis with 2000-3000 British regulars to capture Fort Mercer. Cornwallis landed his force south of the fort and marched north. Inside Mercer, Colonel Greene also received reports of 2000 British approaching from the north as well.

|

| Hessian assault on Fort Mercer |

On November 20, Colonel Greene opted to burn Fort Mercer, evacuate the garrison, and destroy whatever the army could not carry away. The garrison marched north, along the New Jersey side, to join up with other American forces. Cornwallis’ army marched on the fort to find it abandoned. The British occupied the fort, rebuilt the defenses and installed their own garrison.

With both forts taken, the British set about removing the chevaux de frise that still blocked the river from ship traffic. Hazelwood realized that his small fleet would be no match for the British fleet soon headed his way. He burned his remaining ships and marched his crews north to link up with Washington’s Continentals. With the river cleared, Admiral Howe sailed up to join his brother in Philadelphia.

Battle of Gloucester

The Howes had achieved their goal of taking control of the Delaware River and restoring access between the army and navy. But, that did not mean an end to the fighting.

|

| Lafayette |

Greene was joined by the Marquis de Lafayette, who had mostly recovered from his wounds at Brandywine two months earlier. On the night of November 25, Lafayette led an advance force of around 350 soldiers against a force of about 400 Hessians camped at Gloucester, just north of Cornwallis’ main army around Fort Mercer.

The Marquis launched a surprise night raid against the Hessians, driving them back to the main camp. The attack resulted in little more than a skirmish, with the Americans killing or wounding about 40 Hessians, and capturing another 20. The Americans lost one dead and five wounded. Lafayette’s gallantry in the fight, combined with his performance at Brandywine, led Washington to recommend he be put in command of an entire division. General Adam Stephen, who was accused of drunkenness at the battle of Germantown, lost his commend and left the army. Lafayette would replace him as a division commander.

Meanwhile, General Cornwallis resolved not to leave smaller units garrisoned around southern New Jersey. Other than the garrison at Fort Mercer, Cornwallis returned his force to Philadelphia.

Next week, as the war rages around Philadelphia, the Continental Congress finally gets around to finishing the Articles of Confederation.

Next Episode 169 Articles of Confederation

|

| Click here to donate |

|

| Click here to see my Patreon Page |

An alternative to Patreon is SubscribeStar. For anyone who has problems with Patreon, you can get the same benefits by subscribing at SubscribeStar.

Click here to go to my SubscribeStar Page

Further Reading

Websites

Red Bank Battlefield Park: https://www.revolutionarywarnewjersey.com/new_jersey_revolutionary_war_sites/towns/national_park_nj_revolutionary_war_sites.htm

Coudray, Du. “Du Coudray's ‘Observations on the Forts Intended for the Defense of the Two Passages of the River Delaware’, July, 1777.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 24, no. 3, 1900, pp. 343–347. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20085927 or on archive.org: https://archive.org/details/jstor-20085927

Howe, and Marion Balderston. “Lord Howe Clears the Delaware.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 96, no. 3, 1972, pp. 326–345. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20090651

Leach, Josiah Granville. “Commodore John Hazlewood, Commander of the Pennsylvania Navy in the Revolution.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 26, no. 1, 1902, pp. 1–6. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20086007

Mervine, William M. “Excerpts from the Master's Log of His Majesty's Ship ‘Eagle," Lord Howe's Flagship, 1776-1777.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 38, no. 2, 1914, pp. 211–226. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20086167

Syrett, David “H.M. Armed Ship Vigilant, 1777-1780” The Mariner's Mirror Volume 64 Issue 1, 1978, pages 57-62 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00253359.1978.10659065

“Instructions to Colonel Christopher Greene, 8 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0453

“From George Washington to Colonel Christopher Greene, 14 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0511

“From Alexander Hamilton to Colonel Christopher Greene, 15 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-01-02-0312

“From George Washington to Colonel Christopher Greene, 15 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0525

Free eBooks

(from archive.org unless noted)

Adolphus, John The History of England, from the Accession to the Decease of King George the Third, Vol. 2, London: J. Lee, 1840 (p. 457-59).

Ford, Worthington C. Defences of Philadelphia in 1777, Brooklyn: Historical Printing Club, 1897.

McGeorge, Isabella C & McGeorge, Wallace Ann C. Whitall, the heroine of Red Bank, Gloucester County Historical Society (N.J.) 1917.

McGeorge, Wallace The Battle of Red Bank, resulting in the defeat of the Hessians and the destruction of the British frigate Augusta, Oct. 22 and 23, 1777, Camden: Sinnickson Chew, 1905.

Books Worth Buying

(links to Amazon.com unless otherwise noted)*

Anderson, Lee Patrick Forty Minutes by the Delaware: The story of the Whitalls, Red Bank Plantation, and the battle for Fort Mercer, Universal Publishers, 1999.

Dorwart, Jeffery, M. Fort Mifflin of Philadelphia: An Illustrated History, Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 1998.

Jackson John W. The Pennsylvania Navy, 1775-1781: The Defense of the Delaware, Rutgers Univ. Press, 1974.

McGrath, Tim John Barry: An American Hero in the Age of Sail, Westholme Publishing, 2010.

McGuire, Thomas J. The Philadelphia Campaign, Vol. 2, Stackpole Books, 2007.

Reed, John Ford Campaign to Valley Forge, July 1, 1777-December 19, 1777, Pioneer Press, 1980 (orig. Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 1965).

Smith, Samuel Steele Fight for the Delaware, 1777, Phillip Freneau Press, 1970 (book recommendation of the week).

Taaffe, Stephen R. The Philadelphia Campaign, 1777-1778, Univ. Press of Kansas, 2003

Ward, Christopher The War of the Revolution, Macmillan, 1952.

* As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

No comments:

Post a Comment