The Americans were feeling pretty good about themselves in the spring and summer of 1776. They had chased the British Army out of Boston in March, and then declared independence in July. For the patriots, there was no more bickering over taxing authority in London. The United States were now separate from the British Empire.

Britain, though, had no intent of letting this relationship go that easily. After all, you don’t build a world empire by giving away an entire continent just because some rebels kill a few hundred of your soldiers. King George and Lord North had spent the winter assembling the largest military force the Empire had ever sent overseas.

|

| Adm Richard Howe (fromWikimedia) |

Another reason for delay was the assembly of the army and a fleet to carry them. Carrying tens of thousands of troops across the Atlantic was no easy task in 1776. It would require hundreds of transport ships which the government needed to build, buy, or lease. Producing or acquiring all the arms and equipment took time as well. Britain wanted all of this to arrive at once. They wanted shock and awe, not some slow military build up over time.

Finally, even after London had its army and navy ready to go, along with all the equipment, it faced a series of storms in the Atlantic that spring, that delayed passage of most of the fleet for several months. As a result, the British would not be ready to do much of anything before mid summer.

By June, General William Howe in Halifax was itching to go. It had been three months since he evacuated Boston and he was ready to redeem himself. On June 29, 1776 most of General Howe’s fleet reached the waters just off Sandy Hook, NJ, just south of New York City. He had more than 100 ships carrying around 10,000 soldiers. This looked pretty intimidating to the continentals and militia preparing to defend the city. But it was only the first phase. General Howe would await the arrival of his brother Admiral Howe, with a larger fleet, as well as General Henry Clinton and his army returning from the Carolinas. Over the next month, the patriots in New York would simply watch the enemy fleet grow and grow and grow.

Staten Island

Howe was not yet ready to engage the enemy, but he also did not plan to leave his men stuck in ships for weeks while the awaited the remainder of the invasion force. He landed his force on Staten Island, where his men could camp and forage for fresh food.

At the time, Staten Island was lightly populated, with less than 3000 people, and ruled by a handful of prominent families. It tended to be loyalist. While the patriots had been trying to round up loyalists in much of the region, as well as build defenses to oppose a British landing, they had pretty much left Staten Island alone. Most of the islands had been under the guns of the small British fleet that had been in New York’s harbor for the previous couple of years.

On July 2, General Howe began to disembark his troops on Staten Island, facing no military resistance, only a miserable rain storm. The army set up camp and waited. Almost all of the 500 adult males on the island signed oaths of loyalty to the King. The locals happily sold food to the hungry army.

After a few weeks, one officer commented that the good food and comforts of the island had a noticeably good effect on the soldiers. They seemed more energetic and in high morale. According to the officer, one measure of this improvement was the increased number of rapes reported by locals against soldiers. He noted that because the locals failed to bear these attacks with resignation, he got to hear quite a few interesting court martials. Yes, comments like this would probably get any officer kicked out of the army today, but the army of the 1770’s still had a long way to go in sensitivity towards women’s issues.

In any event, the army was regaining its strength and vigor, and the rapes did not seem to create too much ill will among the locals, at least not any that would induce them to change sides. Staten Island became a comfortable base of operations for the British.

Admiral Howe Arrives

About the same time General Howe was approaching New York, his brother Admiral Howe arrived in Halifax. Having found that the General had already departed, Admiral Howe immediately set sail down the coast toward New York.

While en route, Admiral Howe attempted to work out a proclamation to encourage the patriots to surrender, accept a pardon and return to British authority. Although he had no political concessions to offer, Howe relied on the threat of his military force to convince the rebels to give up their cause. If one is faced with the destruction and confiscation of all property, the rape of one’s family, and possibly being hanged, accepting that Parliament can levy a three cent tax on a pound of tea does not seem that outrageous an alternative.

|

| 1776 Map of NY Harbor |

Howe had prepared not only a public proclamation, but wrote letters to the colonial governors (the Royal Governors, not these provincial leaders pretending to be governors), as well as to his friend Benjamin Franklin. You may recall that Howe and Franklin had spent months trying to work out a peace deal in 1774 and 1775 before Franklin finally left England to returned to Pennsylvania. Howe hoped his old friend would assist in bringing the conflict to a peaceful conclusion.

Admiral Howe’s fleet encountered several patriot ships along the way. His fleet captured a Nantucket whaler. Howe released the ship and gave the captain a bottle of brandy to show his good intentions. A day later, he encountered a ship smuggling goods in violation of the Prohibitory Act. Again, Howe released the ship and allowed it to keep its cargo. Howe attempted to give these captains copies of his proclamations to spread among the colonies. However, no one wanted to take them. They feared they might be prosecuted for collaborating with the enemy.

Unfavorable winds and poor weather slowed Admiral Howe’s approach to New York. It also didn’t help that his navigator mistook Nantucket Island for Long Island, taking the fleet off course. Finally on July 12, the first of Admiral Howe’s fleet would arrive at Staten Island. Ships would continue to dribble in over the next few weeks. But even with over 21,000 soldiers now, the Howe brothers continued to wait. They were still expecting nearly 3000 more soldiers from General Clinton’s mission in the Carolinas as well as about 8000 Hessian mercenaries still on their way from Europe. So the Howe Brothers sat and waited.

This also began a pretty familiar theme for the Howe offensives. Neither Admiral Howe nor General Howe seemed in any hurry to defeat the rebels. They moved slowly and methodically, to win their battles. They never moved quickly or rashly to take advantage of surprise or confusion. Remember, General Howe commanded the British attack at Bunker Hill. He was not inclined to charge his men into an entrenched enemy and face another slaughter. He preferred to move on the enemy using care to protect his advancing forces. Moving slowly against the enemy on their own terms meant that the British could be assured of victory. It also usually meant that while they could win a battle, they could not capture the enemy.

Many have argued that the Howes did not want to win. They generally favored the American cause and did not want to crush the colonists. I don’t think they deliberately set out to lose the war, but they also did not seem intent on crushing the enemy either. They seemed to think that, at some point, the rebellion would fall apart on its own after a series of battlefield losses. They did not want a massacre that would create decades of resentment in the colonies. Rather, if they could simply show the colonists that defeat was inevitable, and the terms of surrender were not so bad, that most of them would voluntarily return to the fold. In hindsight, it was a poor strategy. But at the time, it seemed reasonable to many.

Elizabeth Loring

Some have attributed another reason to General Howe’s slow pace to another reason. While in Boston, Howe had met Elizabeth Loring. Elizabeth or “Betsey” had married Joshua Loring, Jr., the son of a British naval officer. By most accounts, Joshua Jr. was a dirt bag. He had held a number of minor positions in the Massachusetts Government and had left Boston with the other Tories in the evacuation to Halifax. Before the war, he had served as Sheriff in Massachusetts, during which time he got a reputation for ripping off suspected criminals and enriching himself. During the British occupation of Boston and in Halifax, he made money supplying liquor to the British Army. As a military contractor he had great incentive to ingratiate himself with General Howe.

|

| Elizabeth Loring (from Geni) |

Whatever her background, it seems that she began an affair with General Howe that became pretty open and notorious. Her husband Joshua seemed to tolerate the affair, eventually being compensated with an appointment as Commissary of Prisoners. The job had decent pay, but Loring enriched himself even more by embezzling money allocated for the feeding and care of American prisoners of war. Loring grew rich while hundreds of prisoners literally starved to death. General Howe, in turn, seemed willing to overlook these crimes against humanity as long as Loring let him enjoy sexual favors with his wife.

Partly, as the result of all this was that General Howe was in no hurry to see the war come to an end, when he would have to return home to his older wife. Instead, he enjoyed long nights of attending shows, drinking, gambling, and sex.

Up the Hudson River

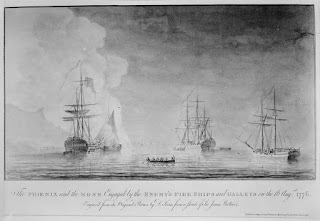

While the Howe brothers seemed in no real hurry to do much of anything, some of their junior officers were chomping at the bit. On July 12, only a few hours before Admiral Howe arrived, the 44 gun Phoenix, the 20 gun Rose and three smaller British ships, caught a favorable wind and sailed up the Hudson River, past Fort Washington and Fort Independence. The Continentals had built these two forts with the specific intent of preventing the British from sailing up the river.

The patriot batteries fired on the ships, but inflicted only minimal damage to the rigging. One sailor had to have a leg amputated. The patriots did more damage to themselves. The inexperienced artillery crews managed to blow up at least one gun. They tried to load a powder charge without first swabbing the barrel. As a result, the powder ignited from a spark still in the barrel from the previous shot, killing six members of the crew and seriously wounding several others.

|

| Phoenix and Rose up the Hudson, 1776 (from Wikimedia) |

For Washington, this was not only a huge embarrassment. It proved that his defenses were worthless against the British Navy. They could sail up behind his forces and cut off his line of retreat whenever they wanted. He also had no idea what those ships planned to do. Some rumors suggested they might be arming Tory regiments to launch an attack on Washington’s rear. Others suggested they might be on a mission to destroy some American ships under construction further up river. They might also be trying to open up lines of communication with General John Burgoyne’s forces who could be moving south over Lake Champlain to complete the British plan of sealing off New England from the rest of the colonies.

If fact, they had no real plans at all other than to test the American defenses. The ship remained upriver for a few weeks, The patriots maintained men along shore to oppose any attempts at landing. After facing a failed patriot raid against the ships and a failed attempt at sending fire ships at them, the ships sailed back down the Hudson, leading to another minor firefight with the Continental artillery, before rejoining the main fleet off Sandy Hook. They did succeed though, in proving to everyone that the American defenses were useless against the British naval domination of the rivers around New York.

Peace Negotiations

The day after Admiral Howe arrived in Staten Island, he began distributing his proclamations as a Peace Commissioner, promising pardons for all who would swear allegiance to the King and making vague and exaggerated claims that he could negotiate a peace and bring the violence to an end. Howe was disappointed to hear the Americans had just declared independence, but still pushed forward with his plans to settle the dispute without further bloodshed.

General Washington used the opportunity to send General Howe a letter, objecting to the treatment of American prisoners, primarily those held in Canada. These men were now prisoners of war of the independent United States, not criminals.

Admiral Howe then decided to send a letter under a flag of truce to “George Washington, Esq.” Washington’s personal aid, Colonel Joseph Reed refused to accept the letter because it was not addressed to General Washington. The British refused to recognize Washington’s commission and could not put his title on the message without tacitly accepting that he was a legitimate commander of a legitimate army.

|

| Joseph Reed (from Geni) |

There, Patterson attempted, once again, to hand deliver Howe’s letter, now addressed to George Washington, Esq, & etc. & etc. This time, Washington himself refused to accept the letter without the proper title. Patterson insisted the Admiral met no disrespect, and that the et ceteras were there to imply all appropriate titles. Washington said that yes, they could mean anything and everything, but he would not even consider a negotiation until they recognized his proper title, which would implicitly mean recognizing American independence as well.

Washington went on to tell Patterson that he understood the Admiral’s only real power was to grant pardons. No one wanted his pardons because they had not done anything wrong. Also, if the British wanted to negotiate any sort of political solution, they needed to do that with the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, not a military general. The meeting lasted several hours, and was apparently reasonably cordial. But neither side seemed to be willing to do anything that would even begin any sort of peace talks. By late afternoon, Patterson put on his blindfolded and was led back to the British ship waiting to carry him back to the fleet.

Howe did get his messages to Congress as well. But they also seemed to fall on deaf ears. Having committed to independence and with Howe having no real authority to offer any political reforms, Congress seemed in no mood to talk. Benjamin Franklin received a private letter from Howe, which he had published in the newspapers along with his reply. In his reply, Franklin noted that the relations had grown so poisoned between the British and Americans that neither could ever trust the other again as fellow subjects. The only way the British could hope to govern America was to break the spirit of the people with the “severest tyranny”. Clearly Franklin’s message was aimed more at Americans who were considering the negotiation option more than it was to Admiral Howe. But it did make clear that the time for talk was over. Only force of arms would decide anything going forward.

More Forces Arrive

With talks going nowhere, the Howes awaited the arrival of their remaining troops. On July 31 and August 1, the fleet arrived from South Carolina with Admiral Peter Parker, General Clinton, and General Lord Cornwallis and 3000 regulars, following their defeat at Fort Sullivan in South Carolina. On August 14 the fleet carrying 8000 Hessians arrived. The soldiers disembarked at Staten Island following a long and difficult crossing.

By this time, the Howes had about 32,000 soldiers, 10,000 sailors and more than 400 ships already to attack New York and begin the reconquest of America. With peaceful negotiations at an impasse, the Howes decided it was time to use their army.

Next Week: before we get to the invasion of Long Island, I want to move south again. The British had failed to establish a base along the Carolina coast, but they had stirred up the Cherokee in the west to fight the patriots. We will take a look at patriot attempts to crush the Cherokee uprising.

- - -

Next Episode 102: Cherokee War in the South

Previous Episode 100 The Declaration of Independence

|

| Click here to donate |

Thanks,

Mike Troy

|

| Click here to see my Patreon Page |

Further Reading

Websites

British Forces Land at Staten Island, the New York Campaign Begins: http://www.revwartalk.com/Battles-1776/07-02-1776-battles-british-forces-land-at-staten-island-new-york-the-new-york-campaign-begins.html

Joshua Loring, Jr - American Revolution’s Public Enemy Number One:

http://tidewaterhistorian.blogspot.com/2010/09/american-revolutions-public-enemy.html

Washington Plays Hardball With the Howes, by John L. Smith, Jr. (JAR) (2015)

https://allthingsliberty.com/2015/11/washington-plays-hardball-with-the-howes

The Enigma Of General Howe, by Thomas Fleming, American Heritage, Vol. 15, Issue 2 (Feb. 1964): http://www.americanheritage.com/content/enigma-general-howe

Journal of HMS Phoenix, July-Aug 1776: http://revwar75.com/battles/primarydocs/phoenix.htm

Journal of HMS Rose, July-Aug 1776: http://revwar75.com/battles/primarydocs/rose.htm

Washington, George Memorandum of an Interview with Lieutenant Colonel James Paterson, July 20, 1776, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0295

Letter from Lord Howe to Benjamin Franklin, June 20, 1776:

https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-22-02-0282

Letter from Benjamin Franklin to Lord Howe, July 20, 1776: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-22-02-0307

Free eBooks

(from archive.org unless noted)

Bouton, Nathaniel (ed) State Papers: Documents and Records Related to the State of New Hampshire, Vol. 8, NH Legislature, 1874.

Carrington, Henry Battles of the American Revolution, 1775-1781, A.S. Barnes & Co. 1876.

Flick, Alexander C. Loyalism in New York During the American Revolution, New York, The Columbia University Press, 1901.

Force, Peter American Archives, Fifth Series, Vol 1, M. St. Claire Clarks, 1837.

Force, Peter American Archives, Series 5, Vol 2, M. St. Claire Clarks, 1837.

Johnston, Henry The Campaign of 1776 Around New York and Brooklyn, Long Island Historical Society, 1878.

Mather, Frederic The Refugees of 1776 from Long Island to Connecticut, 1913.

Tomlinson, Abraham; Dawson, Henry B. New York city during the American revolution : Being a collection of original papers (now first published) from the manuscripts in the possession of the Mercantile library association, of New York city by New York (N.Y.). Mercantile Library Association;

Privately printed for the Association, 1861.

Books Worth Buying

(links to Amazon.com unless otherwise noted)*

Bliven, Bruce Under the Guns: New York, 1775-1776, New York: Harper & Rowe, 1972.

Daughan, George C. Revolution on the Hudson: New York City and the Hudson River Valley in the American War of Independence, New York: W.W. Norton & Co. 2016.

Ellis, Joseph Revolutionary Summer: The Birth of American Independence, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013.

Fleming, Thomas 1776: Year of Illusions, New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1975.

Gallagher, John J. Battle Of Brooklyn, 1776, Da Capo Press, 1995.

Golway, Terry Washington's General: Nathanael Greene and the Triumph of the American Revolution, Henry Hold & Co. 2004.

McCullough, David 1776, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005.

Schecter, Barnet The Battle for New York, New York: Walker Publishing, 2002.

Wheeler, Richard Voices of 1776: The Story of the American Revolution in the Words of Those Who Were There, 1997.

* As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

No comments:

Post a Comment