We last left Canada back in Episode 90 with the arrival of the first British reinforcements arriving in Quebec in May 1776. Even before the main force arrived, the Continentals, then under the command of General John Thomas, began their retreat up the St. Lawrence River to Sorel. There, the St. Lawrence River meets with the Richelieu River, providing a water route back to Lake Champlain and New York.

General Thomas had just arrived in Canada himself, bringing reinforcements. But Thomas, and most of his reinforcements quickly contracted smallpox. By mid-May, Thomas himself was incapacitated and blinded by the disease. General David Wooster resumed command of Continental forces.

Burgoyne’s Relief Force

As the Continentals retreated, the British relief force continued to arrive in Quebec. London had sent General Johnny Burgoyne, the general we met back in Boston when he served as fourth in command behind Generals Gage, Howe, and Clinton. Burgoyne had returned to London in late 1775 because Boston was miserable, he had nothing to do there, and he wanted to return to take care of his sick wife in London.

|

| Gen. John Burgoyne (from Wikimedia) |

The first relief ships began to arrive in Quebec in early May, but the bulk of the force did not arrive with Burgoyne until early June. Once they arrived, the more senior General Guy Carleton assumed overall command, with Burgoyne serving as second in command. Secretary of State George Germain had intended that Burgoyne lead the army, but his letter to Carleton on this point never arrived.

With the 8000 reinforcements, along with the militia and others already defending Quebec, the combined British force reached between 11,000 and 12,000 men. The sight of an overwhelming number of British inspired many local Indian tribes to mobilize in support of the British, as well as many French Canadians to join local militias also backing the British authorities. By some estimates, when you add in sailors, Indian allies, and other support, the entire body reached nearly 20,000.

Even before all the reinforcements arrived, Carlton began to deploy his forces up the St. Lawrence River.

Sullivan’s Relief Force

To contest the British, Washington sent another 3000 Continentals under the command of General John Sullivan. General Thomas finally died from smallpox on June 2 near Fort Chambly on the Richelieu River, the same day General Sullivan arrived. Because Thomas had been too sick too command for weeks, General Wooster had overall command, which he now turned over to Sullivan.

Wooster had been annoyed since he first got his commission as a brigadier general, thinking he should have been a major general. Now, after being replaced a second time as commander in Canada, Wooster decided to call it quits. In July, he resigned his commission and returned to Connecticut. There, he would resume his role as a major general in the Connecticut Militia.

John Sullivan

The new commander, General Sullivan had to contend with more than just an overwhelming enemy. Most of his army was dying of smallpox and most of his officers hated each other.

|

| Gen. John Sullivan (From Wikimedia) |

Mostly because of his wealth and prominence in the community, and a friendship with Royal Governor John Wentworth, Sullivan received a commission as a major in the New Hampshire militia and served in the New Hampshire Assembly. He soon sided with the patriots though and served as a delegate to the First Continental Congress.

In December 1774, Sullivan participated in the raid on Fort William and Mary that I discussed way back in Episode 51. This helped give him credibility as a soldier when he returned to the Second Continental Congress. When it came time to pick Generals, Sullivan became part of the first group of brigadier generals in the new Continental Army.

Sullivan served unremarkably, but also without embarrassing himself, during the Siege of Boston. Now Washington gave him his first real test by trusting him with an independent command in Canada.

Thompson Advances on Three Rivers

Sullivan did not know just how large a force he was facing in Canada. Even if his entire army had been fit for duty, the 5000-6000 men faced a force more than double their size. The fact was though, that more than half of his force was unfit for duty, mostly thanks to smallpox, which continued to ravage the army.

Undeterred, Sullivan committed a large portion of his army to Trois-Rivières, which I am going to call Three Rivers, its English name. Three Rivers sat on the St. Lawrence River, between Quebec where the British were still landing, and Sorel, from which the Continentals were still retreating down toward New York.

Sullivan did not anticipate a simple holding action though. His letters from the time indicate he planned to defeat the British at Three Rivers, then move his invasion force back down the river to Quebec where he would finally capture the city for the Continental Army.

Sullivan deployed General William Thompson with most of his recently arrived reinforcements to retake Three Rivers from the British.

Thompson is someone else I’ve mostly ignored up until now. He had joined the fight at Cambridge a year earlier as the head of a Pennsylvania rifle company. Thompson had not really impressed Washington, since control of the rifle companies became one of his main discipline headaches.

Even so, Thompson’s riflemen successfully fended off a very minor British attack in November 1775, which brought him to the notice of Congress. Pennsylvania’s Quaker tradition left it with few leaders suited for military command. But Congress hoped to represent all the colonies and Pennsylvania was by far the largest State without a general in the army. In March 1776, despite Washington’s reservations, Congress Commissioned Thompson as a brigadier general. Two months later, Washington deployed Thompson along with Gen. Sullivan to help retake Canada.

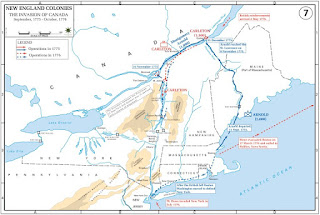

|

| Map of Quebec Campaign (from The History Junkie) |

Tasked to take Three Rivers, on the night of June 7, Gen. Thompson took a force of nearly 2000 Continentals on a night march designed to surprise the relatively small British force there. His forces would arrive at the town the following morning. There, Lt. Colonel Simon Frasier commanded about 1000 regulars, with another 1000 in reserve, mostly still aboard ships in the river.

Thompson and his Pennsylvania soldiers were new to the area and really did not know the land. They hired a local French Canadian guide who was either highly incompetent, or more likely deliberately trying to sabotage their attack. The men had planned to take a trail through the forest where their presence would be hidden from any British ships moving along the river. Instead, the guide convinced them to take the road along the river to clear a house that he claimed contained an enemy outpost. When they arrived, the house was empty.

Rather than track back for several miles to take the trail they wanted, the guide suggested they cut through the forest and connect up with the trail. General Thompson’s force set off, only to find themselves getting stuck in a swamp. Thompson began to question his faith in his guide, and decided to turn around and go back to the river. At the river, an enemy ship spotted them. It opened fire, and then moved down river to alert the main British forces.

The Continental battalion continued to struggle forward, despite losing the element of surprise. They waded through a swamp, sometimes waist deep before finally arriving on the outskirts of Three Rivers.

There, they found a relatively small detachment British waiting for them, already lined up for battle, supported by field artillery, and supplemented with Indian warriors.

|

| Anthony Wayne (from US History) |

Continental Colonel Wayne immediately launched an attack against both flanks of the enemy lines. His attack against the smaller British advance force caused them to break and run. But the British reserves, counterattacked and pushed back Wayne’s regiment. By this time, other Continental regiments had emerged from the swamp and joined the attack. Both sides fought furiously, but the British had the better ground, and were supported by artillery on ships in the river.

Wayne attempted to rally his soldiers, only to find that most had already abandoned him. He had only about twenty soldiers as he finally decided to retreat back into the swamp. Wayne then maintained a rear guard action, firing on the enemy before falling back in order to give time for the main body of Continentals to escape. If Wayne’s bravery sounds impressive, you have to remember that our records of this battle come mostly from Wayne’s own reports. So while he probably did perform well that day, he also had every incentive to make himself sound every bit hero and put all of his actions in the best possible light.

On the field, the Continentals had lost between 30 and 50 dead, we only have a British estimate to go on, and another 30 or so wounded. The British only lost eight dead and nine wounded. Over the rest of the day, the British attempted to capture the scattered retreating Continentals, taking over 200 prisoners, including General Thompson.

Most of the force made its way back to General Sullivan and the main army at Sorel. Many of them staggered in after days in the woods and swamps.

British commander General Carleton arrived at Three Rivers that evening to congratulate his officers and men on their victory. To the disappointment of many, Carleton ordered his army not to pursue the retreating enemy. It’s not entirely clear why, but one officer noted that Carleton commented that he did not want to feed that many prisoners, that he did not want to see them starve in a Quebec prison, and that their arrival back at the Continental Army would only demoralize the enemy.

The British would soon parole General Thompson, but under the terms of his parole, he could not returned to duty until exchanged for a British officer of equal rank. Thompson would spend the next four years in Pennsylvania complaining to anyone who would listen about how Congress was dragging its feet on exchanging him. His complaining eventually led to Congress issuing him a letter of censure as well a successful libel suit from a delegate.

I’ve never seen any documentation on this point, but I suspect that Washington did not want the General back and was happy to keep him sidelined on parole. Finally, in 1780 Thompson would be exchanged for a German officer who had been captured at Saratoga in 1777 and who had also been on parole for several years. Even then, he would never return to active duty and would die a year later in 1781 from natural causes, still living at home in Pennsylvania.

Sullivan Retreats From Canada

Despite the loss of Three Rivers and General Thompson, General Sullivan remained committed to holding Sorel and attempting some sort of counterattack. Meanwhile, General Benedict Arnold had seen the writing on the wall and had been planning to evacuate Montreal since early May. General Arnold realized, even if his commander did not, that there was no realistic chance of holding Canada. The Continentals would have to retreat back into New York and try to prevent the British from establishing a hold on Lake Champlain.

Arnold realized that his small force in Montreal would be cut off from New York if the British seized Sorel. He meant not to get trapped there just because the new commander had some delusion that he was going to recapture Canada.

To assist with the retreat, Arnold had confiscated clothing, supplies, and just about anything else of value to the army from the merchants in Montreal. He promised them that they would be repaid and marked all the goods he packed up with each merchant’s name. He then order an officer named Major Scott to oversee the transfer of the supplies to Fort Chambly. There, the commander Colonel Moses Hazen refused to accept receipt of the goods. It is not clear exactly why. It could be that he objected to the confiscation of goods from his fellow Canadians. It could also be because he just hated Arnold and wanted to annoy him.

|

| Fort Chambly (from Wikimedia) |

British Lt. Colonel Frasier, fresh off his victory against the Continentals at Three Rivers, continued to move his brigade up the St. Lawrence toward Sorel in mid June. Sullivan remained firm that he would defend Sorel or die trying. Meanwhile Arnold was busy moving troops up the Richelieu River toward Lake Champlain where his fleet still on the lake could transport everyone back down to Crown Point and Ticonderoga. He did a great job of transporting all the sick and wounded, as well as military supplies back to safety. Arnold even had the partially built British ship still in dock at Chambly, disassembled and shipped south.

While Sullivan worked on his plan to defeat the British, Arnold saw that the enemy could bypass Sorell, and march overland to capture Fort Chambly, thus cutting off Sullivan’s line of retreat. Finally, on June 13, Sullivan sighted Lt. Colonel Frasier’s advance forces moving on his lines at Sorel. Sullivan held a Council of War at which everyone pretty much said he was an idiot if he planned to stay and fight. Reluctantly, Sullivan approved a withdrawal, and moved his army south in the face of the enemy back to Fort Chambly.

The next day, Gen. Burgoyne landed 4000 regulars and field cannon at Sorel. Another 4000 were on their way up the St. Lawrence River. Somehow, Arnold was back in Montreal when the British took Sorel. Carleton took part of the fleet upriver toward Montreal. But unfavorable winds slowed his approach, giving Arnold time to escape and make his way back overland through Indian infested forests to reach Fort St. Jean.

At St. Jean, Arnold reconnected with Sullivan, who had destroyed Fort Chambly on his way south. The British moved slowly and deliberately, retaking ground, but avoiding any possible ambush. As a result, the Continentals had time to remove or destroy just about anything of value. Among other things, Arnold burned Hazen’s house, which Hazen agreed was the proper course of action. Still, Arnold must have secretly enjoyed that.

Sullivan again called a Council to discuss forming a last stand at St. Jean, but again his officers voted him down. They were in no condition to fight. The army moved further south to Isle Aux Noix near the New York border. There, Sullivan said he would retreat no further without orders from a superior.

Arnold held the rear of the escaping army at St. Jean. He remained on horseback until he could see the enemy approaching. He removed his saddle, and shot his horse to deny it to the enemy. He then boarded the last boat south, back to Isle Aux Noix.

|

| Fort St. Jean (from Wikimedia) |

There was no way to sail ships up the Richelieu River rapids, so British General Carleton would have to disassemble ships, carry the parts to St. Jean, and reassemble them there. That would take months. During that time, Arnold would build up his own navy on the Lake so that he could prevent Carleton’s march south to retake Crown Point and Ticonderoga.

Schuyler also received word that Congress had already decided to relieve Sullivan of command. Sullivan would return to New York, and Gen. Horatio Gates would take command of the Northern Army. This was good news for Arnold. He actually still liked Gates at this point. But Gates and Schuyler disliked each other, leading to more conflict and infighting that the Army really didn’t need. Sullivan attempted to resign his commission, but was persuaded to stay and serve Washington at the Battle of Long Island.

The Continental Army moved back to Crown Point and Ticonderoga. As expected, Carleton did not pursue immediately, but took slow and decisive action to capture Lake Champlain. Both armies would have several months to prepare for the next offensive.

Next Week: The British suffer a surprising defeat in South Carolina at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island.

- - -

Next Episode 96: The Battle of Sullivan's Island

Previous Episode 94: War at Sea, Battle of Turtle Gut Inlet

|

| Click here to donate |

Thanks,

Mike Troy

|

| Click here to see my Patreon Page |

Further Reading

Websites

Gen. John Sullivan: http://www.nndb.com/people/063/000049913

Gen. William Thompson: http://www.aohcumberland2.org/about-us/general-william-thompson

Battle of Three Rivers: http://www.heritage-history.com/?c=read&author=barnes&book=stony&story=trois

Battle of Three Rivers: http://www.revolutionarywar101.com/battles/760608-three-rivers

Free eBooks

(from archive.org unless noted)

Amory, Thomas C. The Military Services and Public Life of Major-General John Sullivan, J. Munsell, 1868.

Carrington, Henry B. Battles of the American Revolution, 1775-1781, A.S. Barnes & Co, 1876.

Coffin, Charles The Life and Services of Major General John Thomas, New York: Egbert, Hovey & King, 1844.

Hill, George Benedict Arnold: A Biography, Boston: E.O. Libby & Co. 1858.

Kingsford, William The History of Canada, Vol. 6, Toronto: Roswell & Hutchinson, 1887.

Smith, Justin Our Struggle for the Fourteenth Colony: Canada, and the American Revolution, Vol. 2, New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1907.

Sparks, Jared (ed) The Library of American Biography, Vol. 3, Little & Brown, 1844 - Includes The Life of John Sullivan, by Oliver Peabody.

Winsor, Justin (ed) Arnold's expedition against Quebec. 1775-1776: The Diary of Ebenezer Wild, Cambridge: John Wilson & Son, 1886.

Withington, Lothrop (ed) Caleb Haskell's diary. May 5, 1775-May 30, 1776. A revolutionary soldier's record before Boston and with Arnold's Quebec expedition, Newburyport: W.H. Huse, 1881.

Würtele, Fred C. Blockade of Quebec in 1775-1776 by the American revolutionists (les Bastonnais) Vol 1) Quebec: Daily Telegraph Job Printing House, 1905.

(links to Amazon.com unless otherwise noted)

Anderson, Mark The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony: America’s War of Liberation in Canada, 1774–1776, University Press of New England, 2013.

Cubbison, Douglas R. The American Northern Theater Army in 1776, Jefferson, NC: Macfarland & Co. 2010.

Fleming, Thomas 1776: Year of Illusions, New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1975.

Martin, James Benedict Arnold: Revolutionary Hero, New York: NYU Press, 1997.

Randall, Willard Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor, William Morrow & Co. 1990.

No comments:

Post a Comment