In late 1776, British war plans seemed to be going reasonably well for the British. In Canada, General Carleton had destroyed General Arnold’s fleet on Lake Champlain, and opened up the path for a spring invasion from the north. General Howe had pushed General Washington out of New York and New Jersey and into Pennsylvania. The patriot cause seemed to be in trouble.

Fort Cumberland

Despite being on the ropes, many Patriots were still looking to take the fight to the British. Some still wanted to go on the offensive. A revolution is not controlled by a single authority. In many places, locals will take the initiative.

Back in March 1776, General Howe had evacuated Boston and moved his forces up to Halifax Nova Scotia before beginning the summer campaign in New York. After Howe’s army left Halifax for New York, there were few British soldiers left in the area. Recall that back at the beginning of the French and Indian war, Britain had removed most of the local French Acadians from the region and forced them to return to France. See, Episode 007. Thousands of colonists from New England moved into the area to take the farmland that the French Canadians had been forced to abandon. During the French and Indian war, it seemed like a good idea for Britain to populate the area with British colonists. But by 1776, those same New Englanders were at war with Britain. The New Englanders who had settled in Halifax shared the same political views as their friends and family in Massachusetts.

|

| Model of Ft Cumberland, Nova Scotia (from Johnwood1946) |

In February 1776, Eddy traveled to Cambridge to convince General Washington to send a contingent to Halifax to take control of the region. At the time, Washington was still besieging Boston and preparing his own offensive there. He did not want to deploy resources to begin another campaign. Eddy then traveled to Philadelphia to get the support of the Continental Congress for a campaign to take Halifax. Congress also rejected his proposals. Finally, he returned to Massachusetts to get the Provincial Congress to assist with his plans. Massachusetts refused to provide him with troops, but promised to provide arms and ammunition if he could raise enough men to attempt a takeover of Nova Scotia.

As I said,by the end of March, General Howe had moved the bulk of his army from Boston to Halifax. But everyone expected it would be leaving soon. Eddy spent most of the summer, attempting to raise a regiment. Despite aggressive recruiting among small villages in northern New England, Eddy could not raise even 100 men. Most men who wanted to fight for the patriot cause, had already left for Boston where they were fighting in the Continental Army.

Undeterred, Eddy took his small force back to Nova Scotia, where he was able to recruit more locals and a few Indians, bringing his force to around 180.

After Howe had departed for New York, there were few British soldiers in the region. Eddy’s force targeted Fort Cumberland, which fell under the Command of British Lt. Col. Joseph Gorham. Like Eddy, Gorham had served as an officer during the French and Indian war, and had settled in Halifax. He received an appointment as Deputy Agent for Indian Affairs. At the same time Eddy tried to recruit a patriot corps, Gorham attempted to recruit a loyalist corps. He also toured much of New England, mostly before the fighting at Lexington and Concord, to put together a fighting force to support the King. Gorham did not have much luck with recruitment either. He ended up with a total command of about 190 men.

|

| Jonathan Eddy |

In early November, Eddy’s forces moved into the area. He recruited more locals, including several members of local tribes as well as some French speaking Acadians who remained in the area. The force captured a small contingent of Loyalist militia under Captain Walker. The patriots also captured a small sloop under Gorham’s command, the Polly along with its crew. Eddy’s forces then began to lay siege to Fort Cumberland. By some accounts, Eddy’s forces had grown to over 500 men, though this seems exaggerated. Gorham had less than 200 in his garrison. Eddy had already taken about 60 men prisoner. However, Eddy had no cannons to use against the fort, while Gorham had three mounted cannons to put into use against the attackers.

On November 10, Eddy sent a letter to Gorham, calling for his surrender. In response, Gorham suggested that Eddy surrender. Two days later, Eddy attempted a night attack against the fort, hoping that surprise and confusion would allow his men to get inside the fort and take the garrison. Gorham’s men, however, repulsed the attack.

|

| Joseph Gorham at Fort Cumberland (from Wikimedia) |

On November 27, a British relief force arrived aboard the ship Vulture. The ship carried 200 reinforcements, mostly Royal Marines under the command of Major Thomas Batt. Two days later, Batt led a counterattack on the patriot lines outside the fort. The British killed or wounded an unknown number of patriots while taking five casualties, two dead and three wounded, themselves.

The patriot forces scattered. Most of the men simply left the fight and went home. The British spent the next few days trying to chase down patriots, but with little luck. They scoured the countryside and captured a few suspected rebels. They also burned farms of those suspected of participating in the attack on the fort or other supporters of the rebellion.

The locals protested the destruction of property. Colonel Gorham offered a full pardon to anyone who surrendered and agreed to take an oath of allegiance, with the exception of Eddy and a few other leaders. This upset Major Batt, who charged Gorham with neglect of duty. Gorham later received exoneration of the charges. The pardon seemed to return the area to loyal obedience and ended the patriot movement there. Eddy, and a few others unwilling to submit, left for Massachusetts.

The battle at Fort Cumberland, also sometimes called Eddy’s Rebellion, ended up being a relatively minor affair involving mostly militia. While some historians argue that a patriot victory there might have brought Nova Scotia over to the patriot side and made it the 14th State, it seems unlikely that the patriots would have been able to hold the territory against an almost certain British counterattack from Halifax. In any event, the British, despite a victory, did not consider it terribly significant.

Occupation of Newport

All of this fighting in Halifax was happening while the British under General William Howe were pushing the Continental Army out of New York and across New Jersey, still moving slowly toward Philadelphia. As I said, General Howe had joined General Cornwallis in New Jersey, slowly pushing Washington’s army into Pennsylvania.

|

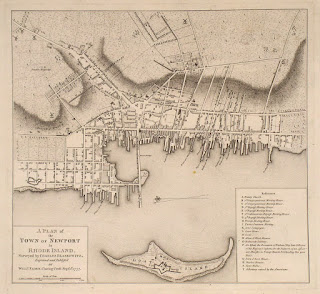

| Newport Map, 1777 (from Boston Rare Maps) |

As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, during the New York campaign, Howe and Clinton’s relationship, which had never been particularly good, grew even more strained. Clinton attempted to push beyond Howe’s orders on several occasions only to receive a reprimand from the commander. During the battle of White Plains, a frustrated Clinton spoke openly of his frustration about serving under Howe to Cornwallis. When Cornwallis passed along these comments to Howe, the commander decided to leave Clinton completely out of any combat plans under his command.

As the British and Hessians pushed the Continental Army across New Jersey, Clinton once again proposed taking a fleet up the Delaware while another army pushed Washington back to the river. Washington’s army would be trapped and forced to surrender. But Howe once again said no, and allowed Clinton’s subordinate, Cornwallis, to lead the British Army attacking Washington in New Jersey.

Still, Howe needed to give Clinton something to do other than sitting in New York writing letters to London about how badly Howe was performing. Howe deployed Clinton to capture Rhode Island, or in particular the island and harbor areas around Newport. General Howe’s brother, Admiral Howe needed a winter port for the Royal Navy. The fresh water areas around New York might freeze up for the winter, thus trapping the navy and possibly damaging the ships. The salt water port at Newport, Rhode Island would be a much safer nearby location to host the Royal Navy for the winter. Newport would also once again give the British a toe hold in New England and would also serve as a good post to block New England privateers from coming and going. Newport was thought to have one of the largest percentages of loyalist populations in New England, thus minimizing the dangers from local militia.

Clinton received a force of about six or seven thousand regulars and Hessians and took General Lord Percy as his second in command. Some sources say the force was larger, but that may have been counting the thousands of sailors aboard ships carrying the army to Rhode Island. Howe had originally promised Clinton a force of 10,000 soldiers, but reduced that number shortly before Clinton set sail.

A fleet of 83 ships under the command of Commodore Peter Parker carried Clinton and his forces troops from New York to Rhode Island. You may recall that Parker had carried Clinton to the Carolinas where they faced the embarrassing loss at Fort Sullivan in Charleston Harbor. See, Episode 96. Clinton certainly had not forgotten about it. He took this opportunity to bicker with Parker again over the incident. He demanded that Parker take the blame for the failure at Charleston and clear the cloud over Clinton’s good name. Parker was pretty conciliatory and wanted to put the issue behind them. But making a fuss about it now only made the situation between the two commanders worse.

Even so, the landing at Newport on December 8, 1776 turned out to be a nonevent. There were no Continental soldiers prepared to oppose the landing. Washington’s army was in New Jersey, fleeing toward Philadelphia. Charles Lee’s army was in southern New York, but seemed more interested in what was happening in New Jersey than attempting to oppose the British in Rhode Island. Before the British fleet arrived, the local patriot militia had abandoned the defensive works along the shore and had already removed their cannons.

|

| Sir Henry Clinton, 1777 (from Wikimedia) |

For the last year, Clinton had constantly recommended to General Howe that he should use forces to envelope the enemy and surround them so that the British could capture the enemy. Instead, Howe just pushed the enemy further back, allowing them an avenue of retreat. Now, Clinton in his first independent command, did exactly the same as Howe. He landed his forces at Newport and simply allowed the enemy militia to flee. Clinton was not interested in taking prisoners. He simply wanted to take Newport as ordered and move on to other things.

The Continental Navy was still hanging around Rhode Island at this time. Most of it remained bottled up near Providence. It did not confront the British or attempt to oppose the landing. In fact, after a British ship, the HMS Diamond, ran aground in January 1777, the Continentals were still unable to capture or destroy it. After the better part of a day, the tide came in and the British sailed on their way. Shortly after that incident, Congress suspended Commodore Esek Hopkins from command of the Continental Navy. The navy remained a nonentity of little concern to the British.

General Clinton was wary about spreading his forces to thinly. He did not attempt to occupy the whole colony but kept his forces in and around Newport. Clinton’s goal was not to occupy large portions of New England. It was to secure a good salt water port for the navy to use over the winter. From there, the Navy could protect its occupation of New York as well as harass patriot shipping all along the New England coast. It also proved once again that the British could take control of any town they wished. The Continental army or militia was not going to stop them. Receiving word of Washington’s attack on Trenton, reinforced Clinton's view that he should not spread his troops too thinly, where small outposts would be vulnerable to a similar attack.

New England militia mobilized about 6000 soldiers in the area around Rhode Island to oppose any attempts to move inland. General Howe, instead of providing reinforcements for an offensive, recalled many of the soldiers under Clinton’s command, for use in New Jersey. As a result the British occupation would remain strictly on the defensive.

Clinton Goes Home

In January, 1777, Clinton turned over command to Lord Percy and returned home to Britain. Clinton was frustrated at not getting any real command opportunity and still felt the need to clear his name over the failure to take Charleston. He also wanted to express his frustration over Howe’s go-slow strategy and refusal to take any advice that might result in the capture and destruction of the Continental Army. Further, Clinton felt slighted by the fact that General John Burgoyne, a more junior general, had been given an independent command in Canada.

Clinton had planned to resign his commission once he returned. As we’ll see in future episodes, the King would not accept his resignation and still had other plans for him. But for the winter of 1777, once Newport was secure, Clinton hopped on a ship and went home to England, expecting that would be the end of his military career.

Percy Goes Home

After Clinton’s departure, General Lord Percy took command for a few months. Then, he too decided to return to London. Percy, who had saved the British during the retreat from Concord, and had led divisions in the Battle of Long Island and the assault on Fort Washington, had also regularly clashed with General Howe. He had proven himself a highly capable officer on the battlefield, and also had the respect of the officers and men who had served under him.

|

| Lord Percy (from Wikimedia) |

Since Percy had followed orders, and since Howe’s attempts in New Jersey to occupy more territory that winter had ended in disaster, it’s hard to say or certain why Howe was so critical. It appears that Howe saw Percy as a Clinton ally and therefore a political threat to Howe’s leadership. By putting Percy in a theater where he would not see much action, and then generally criticizing his failure to impress, Howe seemed to be trying to diminish Percy’s reputation among leaders back in London.

Officials in London seemed perfectly happy with Percy. They even promoted him to Lieutenant General. Despite the promotion, Percy decided to return home in the spring of 1777 and resign his commission. Unlike Clinton, the King accepted Percy’s resignation, ending his military career. General Richard Prescott assumed command of the British forces in Rhode Island. I’ll have more to say about Prescott in a future episode.

Percy seemed content to retire and live out his life in wealth and comfort. He divorced his wife, who had been cheating on him while he was away. He then remarried. He had nine children with his new wife. In 1786 his father died. Percy inherited the family estates and the title of Duke of Northumberland.

Ironically, Americans probably remember Percy’s illegitimate half brother, James Smithson, better than Percy. Many years after Percy’s death, Smithson, who never visited America, left a large bequest in his will which formed the foundation of the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC.

Next week: Thomas Paine will attempt to reinvigorate the Army with his publication of The American Crisis.

- - -

Next Episode 120: The American Crisis

Previous Episode 118 British Capture Stockton and Lee

|

| Click here to donate |

Thanks,

Mike Troy

|

| Click here to see my Patreon Page |

Further Reading

Websites

Jonathan Eddy: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/eddy_jonathan_5E.html

Joseph Gorham: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/goreham_joseph_4E.html

Eddy Rebellion at Cumberland: http://www.blupete.com/Hist/NovaScotiaBk2/Part2/Ch12.htm

The Eddy Rebellion: https://www.albertcountymuseum.com/the-eddy-rebellion

Jonathan Eddy's Account of the Attack on Fort Cumberland:

https://johnwood1946.wordpress.com/2014/10/01/jonathan-eddys-account-of-the-attack-on-fort-cumberland-november-1776

Cumberland Planters and the Aftermath of the Attack on Fort Cumberland, by Earnest Clark:

https://journals.lib.unb.ca/static_content/ACAD/acadpress/theyplantedwell/042-060Clarke.pdf

British and Hessian Forces Occupy Newport and Aquidneck Island in 1776, by Fred Zilian: http://smallstatebighistory.com/british-hessian-forces-occupy-newport-aquidneck-island-1776

Lord Percy: http://www.oshermaps.org/special-map-exhibits/percy-map/percy-biography

Free eBooks

(from archive.org unless noted)

The Detail and Conduct of the American War, under Generals Gage, Howe, Burgoyne, and Vice Admiral Lord Howe, (original reports and letters) The Royal Exchange, 1780.

Field, Edward Revolutionary Defences in Rhode Island, Preston & Rounds, 1896.

Force, Peter American Archives, Series 5, Vol 3, Washington: St. Claire Clarke, 1837.

Kidder, Frederick Military Operations in Eastern Maine and Nova Scotia During the Revolution, Joel Munrell, 1867.

Porter, Joseph Memoir of Col. Jonathan Eddy of Eddington, Me, Sprague, Owen & Nase, 1877.

Books Worth Buying

(links to Amazon.com unless otherwise noted)*

Clarke, Ernest The Siege of Fort Cumberland, 1776: An Episode in the American Revolution, McGill-Queen's University Press, 1995.

McCullough, David 1776, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005.

Willcox, William Portrait of a General: Sir Henry Clinton in the War of Independence, Knopf, 1964.

* As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

No comments:

Post a Comment