For the last few weeks I’ve been talking about how all the colonies rose up almost simultaneously after the battles of Lexington and Concord, threw out the royal governors, and took over their colonies. Officials in London observed the events of 1775 with increasing astonishment and frustration.

|

| Lord North (from Wikipedia) |

There were, of course, some radical whigs in Britain who supported the colonies and said that military force was folly. You may recall John Wilkes from Episode 31. He was the expelled member of Parliament who went to jail for criticizing the King. By 1775, Wilkes was the elected Lord Mayor of London. His council sent a petition to the King calling for reconciliation and an end to the military occupation in America. The King, of course, responded with disapproval. It would be unfair to the law abiding members of his Empire to compromise with the poorly behaved American colonists. The overwhelming consensus in the government was that they could not allow the colonies to get their way by firing on regulars. That sort of opposition had to be met with punishing military force. Otherwise colonies all over the world would start demanding more rights and privileges of their own.

So if the answer was military crackdown, the ministry needed to spend the fall and winter putting the necessary changes in place for a spring offensive.

Gage Gets the Boot

The only significant military actions of 1775 were Lexington & Concord, and Bunker Hill. In both battles, Gen. Gage had achieved his nominal objectives, but at an unacceptable cost. Further, he did not seem to be doing anything to take decisive military action against the rebels. He was supposed to have spent 1775 crushing dissent in Massachusetts and the rest of New England, and arresting the most troublesome leaders of the opposition. Instead, he sat in Boston, crying over his difficult situation and demanding more and more soldiers. Meanwhile sedition spread through all the colonies as political protest turned to armed warfare.

Bunker Hill was the final straw for the ministry. On August 2, three days after receiving Gen. Gage’s report on Bunker Hill, Lord Dartmouth ordered his recall to London and put Gen. Howe in charge of the army at Boston. The language for the recall was a return for consultation. Conceivably they might have considered sending him back. But that was not going to happen. Howe’s command would become permanent the following spring. Gage would never have a field command again. He would remain Governor of Massachusetts, though that was mostly because there was no point in appointing a replacement until Britain had restored control of the colony. Gage would later receive a promotion to full general, so officials did not consider his service a disgrace. But it was time to give another general a chance to resolve this crisis. Gen. Gage was done.

Preparing for a Larger War

Bunker Hill, also made it increasingly clear that the regulars in Boston were not going to be able to break out of the city, at least at current strength. The ministry officials had to choose whether they would consider a political compromise, or up their military game to crush the rebellion. The King clearly favored the latter. In July, the King wrote a letter to Lord Sandwich, the First Lord of the Admiralty: "I am of the opinion that when once these rebels have felt a smart blow, they will submit; and no situation can ever change my fixed resolution, either to bring the colonies to due obedience to the legislature of the mother country or to cast them off!" Lord North and the rest of the ministry seemed to agree.

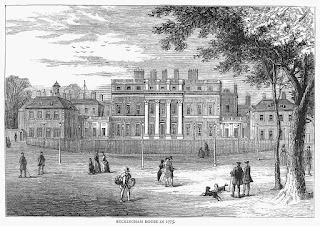

|

| Buckingham House (later Buckingham Palace) purchased by George III in 1761. (from Fine Arts America) |

The British navy began raising and renovating ships for large numbers of troop transports and for sending supplies across the Atlantic to support the larger army they would have in 1776. Military recruiters also spread over England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, raising new regiments and training them for the following year.

Throughout the fall, the Ministry took additional steps to get on a war footing with America. It ordered Admiral Graves to search all ships coming to America for flintstones, commonly used for ballast. It ordered the navy to dump any flintstones in deep water to prevent their use in flintlock muskets. They did not want the colonists to be with the Flintstones, and have a gay old time. Sorry, showing my age with that joke. Kids, ask your grandparents to explain it.

Less than a year earlier, Secretary of State Dartmouth had pretty much laughed at Gage’s request for 20,000 soldiers. Now the ministry was gearing up to send well over 30,000. They all accepted the premise that they needed to hit the colonists with overwhelming force, or this fight could go on for years.

The plans went through several tweaks over the course of the fall but generally, they planned to send two-thirds of the troops to New England and one-third to control the colonies to the south. On September 24, the Ministry announced its intention to "carry on the war against America with the utmost vigour; and to begin the next campaign as early as possible in the spring. The outlines of the plan to be pursued, are, an army of eighteen thousand men to be employed in New-England, and another army of twelve thousand men are to act in Virginia and the middle Provinces."

King Declares Colonies in Rebellion

As part of London’s attempt to ratchet up the war efforts, On August 23, the King issued a Royal Proclamation declaring the colonies in rebellion. The King accused colonists of disturbing the peace, obstruction of lawful commerce, oppressing their fellow subjects and now levying war against the British government.

The proclamation made clear to the colonies that the King was not ignoring out of control Ministers. The King backed the actions of his government and would not tolerate the continued colonial attempts to resist government policy. The proclamation also declared it unlawful for loyal subjects to communicate with the rebels, thus outlawing any backchannel correspondence between the colonies and Britain.

Olive Branch Rejected

About a week later, Pennsylvania Gov. Richard Penn on behalf of the Continental Congress, and Arthur Lee, the colonial agent in London, presented Lord Dartmouth with Congress’ Olive Branch Petition. You remember, the one I discussed a couple of weeks ago where Congress told the King he certainly could not be supporting the violations of rights and liberties perpetrated by the current ministry, and could he please set things right.

Since the King had proclaimed the week before that he was in full support of the ministry’s actions, the success of the petition did not look good. Of course, it did not even get as far as a rejection on the merits. The King refused even to receive the petition, not recognizing the legitimacy of the Continental Congress as a legal body that could petition the King.

|

| London 1775 political cartoon critical of the King. (from Education Library of Virginia) |

On October 27, the King reaffirmed this view in an address to the new session of Parliament. He noted that, despite vague expressions of loyalty to the King, the colonies had created an army and navy and formed their own colonial government independent of royal authority. Their clear intent was to create an “independent empire.” That was unacceptable. The King noted the “moderation and forbearance” of Parliament to resolve ongoing disputes and the colonial refusal to accept reasonable compromises. He would now use “decisive force” against the colonies until the “unhappy and deluded multitude, against whom this force will be directed, shall become sensible of their error.”

In other words, the gloves were coming off. If the colonies wanted a war, they would get a war. No more discussion. No tolerating colonial defiance of the King or Parliament’s authority.

British Support for the Colonies Falters

With the King publicly in favor of war, most British subjects supported their King. In earlier disputes with the colonies, many British manufacturers and workers sided with the colonies if only to end trade stoppages that were putting people out of work. The patriots were counting particularly on the working people of England to stand with them once again, if only for their own economic self-interest.

In the intervening years, though, the economics had changed. In 1774, the Russo-Turkish War ended, opening a huge market for British manufactured goods in eastern Europe. As a result, British workers were not feeling the pain of colonial boycotts against British products. Added to that was the fact that many in Britain were simply tired of colonial complaints. Tories had done a better job in recent years of painting the colonists as spoiled babies who actually had it better than most British commoners. Support for the colonial cause among the British people plummeted as a result.

Germain Replaces Dartmouth

A large majority of Parliament supported the plan to take decisive action against the colonies, especially now that the King and spoken directly and unequivocally on the matter. Still, a significant minority thought this plan was the wrong way to go. Among this minority was Lord Dartmouth, who as Secretary of State for the American Department, would be a key minister in implementing the new policy. Dartmouth decided he could not do this and resigned his post on November 10. In the typical British way, Dartmouth would not be shunted out of power entirely. Rather he received a new position as Lord Privy Seal, which was still in the cabinet but not directly involved in the war with the colonies.

|

| George Germain (from Wikimedia) |

Although passed over for command in North America, Germain served as a general in the European theater. During the Battle of Minden, Gen. Germain refused the orders of the allied commander, the Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick, to send his cavalry to attack the retreating French. The allegation is that Germain did not want the cavalry commander to gain glory for winning the battle. Although the Allies won the battle and protected Hanover from French invasion, Germain’s refusal to obey orders in battle resulted in him being cashiered and sent home in disgrace.

If he had been more astute, he probably would have let the matter drop and begin trying to rebuild his reputation in other ways. But Germain could not let the matter go and demanded a court martial. The court not only affirmed his dismissal, but declared he was "unfit to serve his Majesty in any military capacity whatsoever." To really bury his reputation, the Court then ordered its verdict to be read to every regiment in the army. King George II struck Germain’s name from the Privy Council.

That could have ended his public life forever. Fortunately, when George II died the following year, his successor George III tended to like anyone that his grandfather disliked. Germain, still serving as a member of Parliament slowly built favor with the new King and his ministers, including Lord North. In 1769, a distant relative died and left Germain some land. This was when he changed his name from Lord Sackville to Lord Germain.

Germain’s positions in Parliament consistently favored taking a harder line against the colonies. Now that the North Ministry was ready to take a very hard line, Germain seemed like a good candidate to oversee the Ministry’s war in America as Secretary of State for Colonial Affairs.

Renting an Army - the Hessians

With Germain now in place as Secretary of State, the Ministry pushed forward with its plans to raise and deploy 30,000 soldiers in America.

The wealthy aristocrats running the government were ready to compel obedience whatever the cost, but the British people were in no mood to pay higher taxes to build the necessary army. High debt from the last war would make loans more difficult and more expensive. Even so, it had to be done. In August, King George began looking at the option of hiring German armies to supplement recruiting from home. Renting German troops would actually be cheaper than raising British troops since German soldiers received even lower pay than the poorly paid British soldiers. German princes, eager to raise cash and give their armies something to do in peacetime, were willing to make a deal. The King began negotiations in Europe for a rented army.

|

| Hessian Soldier (from Kokomo Herald) |

During the late summer and early fall of 1775, the King reached out to Russia, but Empress Catherine would not assist him. The King finally struck a deal with the German State of Hesse-Kassel. Hesse-Kassel was a neighbor of King George, who was still the Elector of Hanover. The Prince of Hesse-Kassel was a son-in-law of King George II, although his wife, George III’s Aunt Mary, had died a couple of years earlier. Hesse-Kassel was a small but heavily militarized state. All boys had to register for service, beginning at age seven, and could be drafted as early as age 16. All males had to serve in the military and drill a few weeks each year, unless they received an exemption from the Prince. If you were unemployed or got into legal trouble, you would quite likely find yourself enlisted in the army.

The single largest source of revenue for the state was renting out soldiers as mercenaries. Like the British army, discipline was brutal and pay was terrible. But civilian pay for unskilled laborers in Hesse was even worse than military pay. Also, families of soldiers in Hesse got certain tax breaks and other benefits. These encouraged families to enlist some of their children in the army. The State also instilled the value of militarism in its people, who took pride in the state’s military reputation.

In November 1775, King George informed Lord North that he had contracted to have 4000 Hessians sent to America to supplement British troops. These were the first of nearly 30,000 Hessians and other German speaking mercenaries who would come to America over the course of the Revolution.

France Takes an Interest

With the Britain’s political dispute with the colonies erupting into all out war, the French government began to perk up and take notice. France was still smarting from its loss to Britain in the Seven Years War, just over a decade earlier, where among other things it lost Canada. France was still recovering from that war and was in no mood to start another one with Britain. At the same time, if France could do anything to make life more difficult for Britain and force the British to expend men and resources in America, France would be happy to facilitate that. It was not only payback, keeping one’s enemy weak helped to prevent that enemy from starting a future war against you.

|

| Charles Gravier, comte de Vergennes, (from Wikimedia) |

Bonvouloir made his way to Philadelphia. There he began to assess the state of the rebellion. He made contact with key members of Congress and hinted that France might be willing to provide some form of covert assistance. Bonvouloir’s reports to Paris created the opening that would eventually establish an alliance between France and America that was critical to winning the war.

Outwardly, France was making no moves that would incur British wrath. Paris issued a ban on the sale of any war munitions to American merchant vessels. Despite this ban, American merchants covertly purchased French munitions at the French colony of Hispaniola, what is today Haiti. By banning the trade and then turning a blind eye to violations of the ban, France could avoid war with Britain while still providing some assistance to the new rebellion.

Prohibitory Act

As 1775 came to an end, the North Ministry prepared to ship its armies off to America so that they would arrive in time for an early spring offensive.

Britain had already banned the colonies from trading with any entity other than Britain, and the colonies themselves had already imposed a trade ban on Britain in protest of the Coercive Acts. So effectively the two sides had already outlawed all trade. In December though, Parliament passed the Prohibitory Act, which barred all commerce and trade with the North American Colonies.

Unlike earlier trade restrictions, the new law authorized the navy to capture any colonial ship just as they would any ship belonging to a wartime enemy. Ships and cargo would be seized, taken to Admiralty Court, and if found to be involved in colonial trade, sold at auction. The ban also applied to ships of other countries that traded with the colonies. In essence, the British navy planned to blockade the entire coast of North America. So with all this in place, Britain prepared to start its war in earnest the following spring.

- - -

Next Episode 72 The Siege of St. Jean

Previous Episode 70: Ousted Governors and Bermuda Powder Raid

|

| Click here to donate |

Thanks,

Mike Troy

|

| Click here to see my Patreon Page |

Visit http://www.amrevpodcast.com for a list of all episodes.

Visit https://pod.amrevpodcast.com for free downloads of all podcast episodes.

Further Reading:

Websites

Proclamation of Rebellion Aug. 23, 1775: https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=818&pid=2

King’s address to Parliament, Oct. 26, 1775: https://www.ushistory.org/Paine/more/kingspeech.htm

George Germain: http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1754-1790/member/sackville-lord-george-1716-85

The Hessians: http://www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia/article/hessians

Rupper, Bob "Reconciliation No Longer an Option" Journal of the American Revolution, 2014: https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/11/reconciliation-no-longer-an-option

The unlikely Spy (Bonvouloir): http://www.ushistory.org/carpentershall/history/french.htm

Free eBooks

(from archive.org unless noted)

Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts Report on the manuscripts of Mrs. Stopford-Sackville, of Drayton House, Northamptonshire Vol. 2, Hereford: Hereford Press, 1910 (includes Germain’s correspondence related to America).

Cumberland, Richard Character of the late Lord Viscount Sackville, London: C. Dilly, 1785.

Donne, W. Bodham (ed) The correspondence of King George the Third with Lord North from 1768 to 1783, Vol 1, London: John Murray, 1867.

Force, Peter American Archives, Series 4, Vol 2, Washington: Clarke & Force, 1837.

Books Worth Buying

(links to Amazon.com unless otherwise noted)

Beck, Derek, Igniting the American Revolution 1773-1775, Naperville, Ill: Sourcebooks, 2015.

Beeman, Richard R. Our Lives, Our Fortunes and Our Sacred Honor: The Forging of American Independence, 1774-1776, New York: Basic Books, 2013.

Brown, Gerald Saxon The American secretary: The colonial policy of Lord George Germain, 1775-1778, Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan Press, 1963 (book recommendation of the week).

O’Shaughnessy, Andrew Jackson The Men Who Lost America, New Haven: Yale University Press, 201

Phillips, Kevin 1775: A Good Year for Revolution, New York: Penguin Books, 2012.

Watson J. Steven & George Clark The Reign of George III 1760-1815, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1960.

Whiteley, Peter Lord North: The Prime Minister Who Lost America, London: Hambledon Press, 2003.

No comments:

Post a Comment