Despite the ongoing street riots in various colonies during 1768 and 1769, no one had been killed as a result. In 1770, that would change.

The Death of Christopher Seider

By the end of 1769, merchants began to waver in their resolve of the non-importation agreements. These were the agreements to to protest the Townshend acts, which had been in place for two years. The agreements were hurting merchants in Britain, but they were also hurting the colonials. Some had always cheated, and some loyalist merchants had refused to participate. As a result, the cheats and loyalists were benefiting at the expense of patriot merchants who upheld the agreements. Eventually, more and more merchants would have to give up their resolve and resume trade.

|

| Broadside attacking a Boston merchant for violating the non-importation agreement (from Mass. Historical Society) |

Eight prominent Boston merchants, however, refused to sign any extension. The eight holdouts found themselves named as traitors in a broadside published all over town. One tactic the Sons of Liberty used was to post signs in front of the stores that had refused, in order to keep customers away. On February 22, 1770 a group of boys posted a sign in front of one of the holdouts’ store. Another man, Ebenezer Richardson attempted to run over the sign with a horse and carriage he had borrowed.

Richardson already had a bad reputation. He had been a customs informer and was now working for the Customs Board. Many thought he had been the informant on Daniel Malcom that I discussed in Episode 25. Richardson immediately found himself a target as the boys pelted him with rocks and chased him into his house. They continued to throw rocks, smashing his windows and hitting people inside. The size of the mob increased as men joined the mob, threatening to kill Richardson.

Richard showed his face several times, threatening the growing mob. But that only seemed to enrage the mob even more. At some point, Richardson decided it was a good idea fire a musket full of bird shot into the assembled crowd in front of his home. His shot, and wounded two young boys. One of them, Christopher Seider (sometimes reported as Snider), a boy about 11 or 12 years old, died from his wounds later that evening. Some historians argue that Seider should be considered the first casualty of the American Revolution.

|

| Sketch of Richardson firing from his house into the crowd, killing Seider (from Boston 1775) |

The death of a child only made the situation worse. Christopher Seider’s funeral on February 26 drew thousands of mourners. It soon turned into a rally where Samuel Adams and others spoke to the crowds about British tyranny and the occupation by British Regulars.

Boston Fights with the Soldiers

This may be a good time to address the question, what the heck were the soldiers doing? Weren’t they supposed to be in Boston to maintain law and order? Why were mobs of thousands roaming the streets without military opposition?

Although soldiers were in Boston, they did not do law enforcement unless the Governor requested their help. Like his predecessor, Gov. Hutchinson feared the consequences of calling on the army to do anything. Even as his two sons, who were tea importers, suffered ruthless harassment throughout 1769, he knew that calling in soldiers would only enrage the people and probably lead to a mob trashing his house again, or perhaps worse.

The soldiers maintained a guard on the customs house. As we saw with the George Gailer tar and feather incident a couple of weeks ago, the soldiers did not get involved in violence even when it happened right in front of them.

|

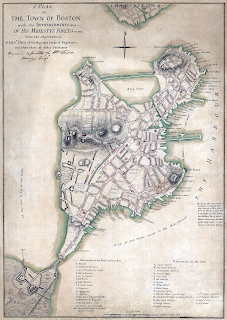

| Town of Boston, 1770s (from Wikimedia) |

The townspeople did their best to make the soldiers feel unwelcome, but typically limited attacks to name calling, or other minor incidences. There are a few reports of fights between off duty soldiers and locals. Newspapers exploited every minor incident they could find. One example from July 19, 1769 when a soldier named John Riley was being taunted by the local butcher. Riley knocked the man down. The butcher complained to to commanding officer who said he was glad Riley had taught him a lesson. The butcher then had Riley arrested, after which he was convicted of assault and fined. Riley then refused to pay the fine and attacked a constable who tried to arrest him.

Bostonians resented the British occupation for a whole range of reasons I already discussed. These included having to pay for the soldiers’ living costs and their use in enforcing the hated customs laws.

Beyond those reasons, there were the inevitable disputes related to almost any military occupation. Within weeks of arriving in Boston, dozens of soldiers deserted their posts and left to start a new life in the colonies. As a result, a big part of military duties involved posting guards to keep deserters from leaving Boston, and sending search parties into the countryside looking for deserters.

Of course, Bostonians did not like being stopped at military checkpoints all the time. After dark, drunken Bostonians, at times, assaulted guards at checkpoints. Similarly, many civilians filed complaints over overzealous guards who threatened or assaulted them.

Boston had its own civilian night watch. Night watchmen stopped anyone on the streets after dark. British officers and soldiers took offense at being stopped by civilians to answer their questions. Military protests that their people were above the law and did not have to answer to civilian law enforcement remained a continuing source of tension at night. Both night watchmen and soldiers were attacked and beaten on multiple occasions.

Soldiers tend to be young single men, who get into trouble with drinking and womanizing. Drunk soldiers frequently got into brawls with civilians in taverns. Soldiers would also hit on local women, or just make lewd comments at them. This also led to fights as local pounced to defend the honor of their women. There is one account of drunk officers encouraging slaves to rise up against their masters, telling them that the soldiers were there to bring them freedom if they would only fight for it. Encouraging slave insurrection, was of course a serious crime. So this incident got a fair amount of attention at the time. It’s not so much remembered now as later generations wanted to forget about Massachusetts’ history of slavery.

There were also accounts of soldiers committing petty crimes, burglarizing homes, stealing property at checkpoints, and other minor matters. Newspapers even reported an attempted rape, although this does not seem to be true.

Even when soldiers were doing their duty properly, they still managed to annoy the locals. Many complained about interruption of church services on Sunday as soldiers shouted out orders on the streets outside.

At the same time, civilians regularly picked fights with the soldiers, levied numerous complaints about exaggerated or even clearly invented wrongdoing. Soldiers on or off duty were regularly taunted. Children would often throw rocks or snowballs at soldiers and then run away.

Col. Dalrymple, commander of British troops in Boston put it this way: “I don’t suppose my Men are without fault, but twenty of them have been knocked down in the Streets and got up and scratched their heads and run to their Barracks and no more has been heard of it whereas if one of the Inhabitants meets with no more than a Kick for an Insult to a Soldier, the Town is immediately in an Alarm and not one word the Soldier says in his justification can gain any credence.”

Both sides developed a bunker mentality. Complaints against soldiers often went ignored or received extremely minor punishment. Similarly, legal actions in local courts by soldiers against civilians who wronged them, regularly found their cases dismissed, or summary findings for the defendant. Both sides came to realize that legal remedies were impossible. Only street justice would provide satisfaction for wrongs.

Workmen though, had yet another reason to dislike the soldiers. Many of the poorly paid soldiers took odd jobs while off duty. They were willing to work for lower rates, thus reducing wages for all laborers. So the competition for jobs increased rivalries and friction between soldiers and civilians.

The same week as Christopher Seider’s funeral on Feb. 22, Boston newspapers reported accounts of the Battle of Golden Hill in New York. This news only served to increas tensions on both sides. Everyone remained on edge, looking for a fight.

Rumbles with the Regulars

On March 2, Private Thomas Walker, a British regular walked down the street past John Gray’s Ropewalk, a rope making enterprise. A rope maker named William Green called out to Walker, asking if he wanted to work. Walker responded yes, to which Green retorted “then go and clean my shit house.” The exact wording of the retort is a matter of dispute, but it clearly angered Walker.

Exactly what happened next is also a matter of dispute. Walker claims that the workmen then jumped him and beat him up unprovoked. Green claimed that Walker came over and struck him, resulting in the fight that left Walker badly beaten. He also claimed Walker dropped a sword during the fight, which he kept.

A short time later Walker returned with 30 or 40 soldiers from his regiment, and called out Green and his fellow rope makers. Both sides were armed with nothing more than clubs or sticks, but a massive street brawl ensued. The soldiers quickly became outnumbered as more local workers joined the brawl. The soldiers eventually retreated. Several of them had to be hospitalized for their wounds. Fighting continued for the next two days with both soldiers and civilian workers attacking others on site. Fighting finally seemed to subside on Sunday March 4. Tension and ill-will between the two groups remained at an all time high.

The Massacre

Monday March 5, 1770 started out with this tense foreboding. Most of the day passed with little violence. However, large numbers of Bostonians roamed the streets. Rumors swirled that British soldiers might attempt to burn some buildings that evening. Both sides expected another street brawl. Gangs of armed civilians were alert and ready for action, just in case the soldiers decided to make more trouble.

Even after sundown, the frozen streets remained alive with activity. Boston did not yet have lighting for its streets, so groups of soldiers and civilians either had to carry a candle or make their way through the darkness.

Around 8 PM, Captain John Goldfinch walked down King Street, near the Customs House. A young wig maker's apprentice named Edward Garrick, commented loudly to his friends that the officer was a deadbeat who had not paid his master for a hair treatment. His exact words, like much of the evening’s events, are a matter of dispute.

|

| State St., (formerly King St.) Boston, painting from 1801. The red building on the right is the Customs House, where the Massacre occurred. (from Rev. War and Beyond) |

He confronted the boy and said something about the officer being an honorable gentleman who paid his debts. Garrick then made some insulting comment directly at White. We don't know exactly what he said, but some accounts say it was something like there are no gentlemen in your regiment.

White approached Garrick and said “let me see your face”. Garrick stood up to him and said “I am not ashamed to show my face.” White then hit Garrick on the ear with the butt of his rifle, knocking him to the ground.

The boy's screams quickly caused a group of mostly boys and young men in the area to confront the lone sentry. Within minutes, White found at least a dozen apprentices, mostly teenagers, surrounding his post, calling him names and daring him to come fight them. Garrick's cries and the boys’ shouts only caused the crowd to grow quickly. Those roaming bands of civilians moved toward White’s guard house, surrounding him.

After a few more minutes, the crowd grew to over 50 people. Someone rang the bells in a nearby church (taken as an alarm bell) which drew even more people. Private White backed up to the top of the stairs in front of the Customs House so that he was elevated and no one could get behind him. He fixed the bayonet on his musket and loaded it.

There were several customs officials still in the Customs House. White banged on the door with the butt of his gun to be let in. No one dared open the locked door for him though. He remained alone on the stairs facing the mob in the dark.

A local bookseller named Henry Knox, who would go on to bigger things in the revolution, warned White not to fire on the crowd, or they would kill him. White responded angrily, “if they molest me, I will kill them.” The crowd began pelting White with snow and ice. Finally White yelled to “call out the guard.” The main guard was only about a block away from White and the Customs House.

At the same time, there were several other fights between soldiers and civilians around the town. The officers were making every effort to get the soldiers into barracks to prevent a fight. The soldiers were in no mood to retreat and wanted a confrontation. So getting them into barracks while mobs of men and boys harassed them remained difficult.

At the main guard. Captain Thomas Preston served as officer of the day. Civilians reported to him about White’s situation and the danger that the mob might carry him off. Preston delayed doing anything for about a half hour, perhaps hoping the mob would eventually disperse on its own. Taking more soldiers into the mob might only make things worse. Eventually he assembled a corporal and six privates to relieve Private White. The squad’s lieutenant, a twenty year old boy, could have led them, but Cap. Preston decided to lead the squad himself.

Preston marched the soldiers with fixed bayonets and unloaded muskets through the crowd to the Customs House. He ordered Private White to fall in with the squad and attempted to march everyone back to the main guard. However, the mob, now numbering in the hundreds by some accounts, pressed around the squad, preventing them from leaving.

The soldiers formed a defensive semi-circle line with Captain Preston in front of them. The mob continued to yell and throw snowballs, ice, and rocks, daring the soldiers to fire. Perhaps hoping to intimidate the mob, Preston ordered his men to load their muskets. This only seemed to enrage the crowd.

|

| The Boston Massacre by Paul Revere, 1770 (from Boston Discovery Guide) |

After the first shot, there were several seconds, some witnesses say a minute or two, as some in the crowd attempted to run, while others pressed forward. The others soldiers also fired their weapons into the crowd. Preston, having recovered from his fall, angrily asked why they had fired. They said they thought they had heard him order them to fire.

By this time the entire 29th Regiment was in formation under arms. They turned out in a defensive formation. A few hundred soldiers would not fare well against an angry and armed mob of thousands. Fortunately the mob opted not to wage a full scale attack against the regiment and retreated.

The situation remained tense though, until Gov. Hutchinson arrived on the scene. He promised that the soldiers responsible would be tried for murder. The soldiers returned to their barracks and the crowd dispersed. Groups of armed civilians, however, continued to patrol the streets.

The Casualties

As a result of the fire, three men died instantly. Crispus Attucks, a sailor of African and Native American descent, was in his late 40s and had been at the front of the mob taunting the soldiers. He had been active with the Sons of Liberty. Samuel Gray, age 52, a rope maker who had been involved the fights with soldiers over the previous few days, also died . James Caldwell, age 17, served as a sailor. He had no family in Boston so little is known of his background.

Eight others suffered wounds. One of them, Samuel Maverick, died the following morning. A 17 year old carpenter’s apprentice, Maverick had been at the front of the mob daring the soldiers to fire. The final fatality, Patrick Carr died nine days later. Carr was a 30 year old Irish immigrant. He had lived long enough to testify about the incident that night. Because he said the soldiers had shown great restraint and that he forgave them, the radicals tried to discount his testimony as that of a Papist who did not appreciate liberty.

Next Week: we will discuss the fallout from the Massacre, as well as the long awaited repeal of most of most of the Townshend Duties.

Next Episode 34: Massacre Fallout & Townshend Acts Repealed

Previous Episode 32: The Battle of Golden Hill

Visit the American Revolution Podcast (https://amrev.podbean.com) for free downloads of all podcast episodes.

Further Reading:

Web Sites

Christopher Seider (aka Snider) murder:

http://www.celebrateboston.com/biography/christopher-snider-murder.htm

More on Christopher Seider (aka Snider):

http://boston1775.blogspot.com/2006/05/christopher-seider-shooting-victim.html

(You may want to explore this blog further. Lots of good articles on Boston just before the Revolution).

A traitor in my family tree (Ebenezer Macintosh) https://nutfieldgenealogy.blogspot.com/2018/02/a-traitor-in-my-family-tree.html

Two good blog articles on the March 2, encounter that led to fighting between the soldiers and citizens of Boston:

http://boston1775.blogspot.com/2007/03/brawl-at-grays-ropewalks.html

http://boston1775.blogspot.com/2006/11/colonial-boston-vocabulary-little.html

Scene of the Boston Massacre: http://boston1775.blogspot.com/2013/03/charles-bahne-on-scene-of-massacre.html

The Boston Massacre

https://historicaldigression.com/2010/10/26/pvt-hugh-white-and-the-boston-massacre

To learn more about how Boston expanded its land mass, check out this HUBhistory podcast episode: http://www.hubhistory.com/episodes/episode-61-annexation-making-boston-bigger-150-years

Tour guide covering key historical and other sites in Massaschusetts:

https://www.your-rv-lifestyle.com/best-things-to-do-in-massachusetts

Free eBooks

(from archive.org unless noted)

A Fair account of the late unhappy disturbance at Boston in New England, London: B. White, 1770 Loyalist account of the Boston Massacre, written in the days following the event.

Boston Registry Dept. Records Relating to the Early History of Boston, Vol. 18, Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, 1887.

Orations, delivered at the request of the inhabitants of the town of Boston, to commemorate the evening of the fifth of March, 1770, Boston: Wm. T. Clapp, 1807 (collection of annual speeches remembering the Massacre on its Anniversary, 1771-1783)

Bowdoin, James; Warren, Joseph; & Pemberton, Samuel A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston, New York: John Doggett, Jr., 1849 (this is a reprint of the original 1770 pamphlet produced in London by Patriot citizens of Boston).

Chandler, Peleg W. American criminal trials, Vol. 1, Boston: Charles Little & James Brown, 1844 (Boston Massacre Trials).

Hosmer, James Samuel Adams, Boston: Houghton-Mifflin Co. 1913.

Hutchinson, Thomas & Hutchinson, John (ed) The History of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, from 1749 to 1774, London: John Murray 1828 (This book was edited and published using Gov. Thomas Hutchinson’s personal papers. The editor was his grandson).

Hutchinson, Thomas & Hutchinson, Peter Orlando (ed) The Diary and Letters of His Excellency Thomas Hutchinson, Boston: Houghton-Mifflin Co. 1884 (Editor is Thomas Hutchinson’s great-grandson).

Kidder, Frederic History of the Boston Massacre, March 5, 1770, Albany: Joel Munsell, 1870.

Books Worth Buying

(links to Amazon.com unless otherwise noted)*

Archer, Richard As If an Enemy's Country: The British Occupation of Boston and the Origins of Revolution, Oxford: Oxford Univserity Press 2010.

Fowler, William The Baron of Beacon Hill: A Biography of John Hancock, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. 1980.

Knollenberg, Bernhard Growth of the American Revolution 1766-1775, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund 1975.

Miller, John Origins of the American Revolution, Stanford, Stanford University Press (1943) (also available as a free eBook, see above).

Smith, Page A New Age Now Begins, Vol. 1, New York: McGraw-Hill 1976.

Zobel, Hiller The Boston Massacre, New York: WW Norton & Co. 1970.

* (Book links to Amazon.com are for convenience. They are not an endorsement of Amazon, nor does this site receive any compensation for any links).

This is all very interesting. I'm enjoying listening to several podcasts a day. It's too bad women didn't exist in the 1700's though.

ReplyDeleteNot an attempt to rewrite history just looking for the other half

Delete