Last week, we talked about the end of the the Seven Years war with the Treaty of Paris in 1763. With the war over, American colonists began paying more attention to domestic issues. Today I want to look at three issues that begin to define how the colonists were beginning to see their interests as separate from those of Britain.

The Parson’s Cause

The first, the Parson’s Cause, flared up in Virginia during the war. According to colonial law, the colonial government paid ministers (Church of England only, of course) with tax money. Because real gold and silver money was so hard to come by in the colonies, and paper money varied so much in value, payments to ministers came in a more stable currency, tobacco. The most recent law of 1748, passed by the Colonial legislature and approved by the King’s Privy Council, permitted each minister to be paid 16,000 pounds of tobacco annually. The minister could resell it locally, smoke it, or ship it off to London. In practice though, the Burgesses paid ministers the cash equivalent of 16,000 pounds of tobacco in Virginia currency.

While tobacco retained good value every year, like any commodity, its value also fluctuated greatly depending on supply and demand. In some years the price was so low, that the legislature had offered supplemental payments to ministers. In 1755, though, the price of tobacco soared and the ministers would have gotten quite a benefit. The price was also high because tobacco crops came in short that year, meaning the rich plantation owners were doing worse previous years. Since the House of Burgesses was run by plantation owners and not ministers, they found it quite reasonable to require ministers be paid that year in paper currency at 2 pence per pound of tobacco, well below market rates. For 16,000 pounds of tobacco, that would be about £133 in Virginia currency, which was worth less than British pounds sterling. The legislature wisely set the pay change to last only 10 months, which meant by the time any complaints reached London, and policies overridden and returned to Virginia, the period of change would be pretty much complete. As a result, the ministers grumbled but did nothing.

Then again in 1758, tobacco prices reached extreme highs, though this time there was no particular shortage, just high prices because of heavier demand. It should have been a good year for everyone. Still, though, the plantation owners saw no need to give the ministers a bonus and again offered £133 in Virginia currency for the year. Since paper was depreciating even faster this year, the ministers had an even worse deal than in 1755, and this law covered two full years.

This time, the ministers appealed to the governor, who passed the buck over to London. In response, the Privy Council in London sent back an opinion that essentially said: The law approved by the King guarantees the value of 16,000 pounds of tobacco. You cannot simply break that contract retroactively and pay less, especially through a law not approved by the King. With that ruling in hand, several ministers went to court in Virginia to get their money.

The local courts, however, did not agree with the Privy Council. Several local juries, in no hurry to give extra cash to ministers, simply found for the defendants and refused to award any damages. Everyone understood that more money to all the ministers only meant higher taxes for everyone else. Also, many Virginians were not even Anglicans in the first place, and objected to payments to Anglican ministers only. Therefore, local juries were not particularly inclined to hand over large awards in court, no matter what the law said.

|

| Patrick Henry by G. Matthews (From Wikipedia) |

They hired a new young lawyer who had been practicing for less time that this case had been in dispute. Patrick Henry became a lawyer in 1760, after spending several weeks reading legal cases at a Virginia law office. The case had taken years to reach this damages trial in 1763. Defendants hired Henry hoping he could work some magic, despite the facts and the law being on the plaintiff’s side.

The plaintiff’s attorney made the damages case short and simple. He put up two witnesses attesting to the value of 16,000 pounds of tobacco in 1758. Given that value, and subtracting what the ministers had already received, that was the damages. OK, now the Jury can see the math, render its decision, and we can all go to lunch.

Henry used a legal technique once described to me by a law school professor: if the law is not on your side, pound on the facts. If the facts are not on your side, pound on the law. If neither is on your side, just pound on the table. Henry simply ignored the facts and law of the case as they were clearly against him. Henry gave a long speech to the jury lasting several hours.

|

| The Parson's Cause, 1763 by George Cooke, 1834 (from Wikipedia) |

Although several judges on the panel thought his speech was treason, they did not cut off his argument. The jury, on the other hand, was much more disposed toward the argument and awarded the plaintiff one penny in damages. This case made Patrick Henry a local hero and sees his new practice grow rapidly.

Aside from introducing young Patrick Henry, who will play more of a role later in our story, this case also shows how colonists viewed the importance of juries in ensuring that laws were executed as the people saw fit, not as those in London many have wanted. It also served as an example to the British that American juries could not be trusted to enforce the law. Finally, it provides some insight into the growing American frustration with having to pay taxes to support ministers that they did not particularly like.

Old Church in New England

If the Parson’s Cause showed how much Virginians disliked excessive taxes, objected to interference from London in local affairs, and were not fans of the Church of England, you could probably multiply those sentiments several times over when it came to the colonists in New England.

The Puritans, of course, founded Massachusetts for the primary purpose of getting away from the Church of England. They wanted to practice their Congregationalist form of Protestant Christianity. Technically, the Puritans only wanted to “purify” the Church of England, also called the Anglican church and today called the Episcopal church. But in practical terms, the Congregationalism practiced in New England was entirely separate from the Anglican Church. Leaving aside the many doctrinal differences, one big structural difference was that they did not rely on Anglican Bishops to appoint ministers. Local parishes controlled hiring ministers and just about everything else related to the local church.

|

| King's Chapel - Boston (from Wikimedia) |

The Anglican Church had several mission churches in the colony, dedicated to converting local Indians to Christianity. The reality, though, is that almost no Anglicans nor Congregationalists put much effort into missions work by the 1700s. It probably did not help the cause that early conversions and creation of Indian “praying towns” ended up with the Christianized Indians eventually being killed or forced out of their lands. That seemed to put a damper on more Indians joining such towns.

In 1760 though, the Anglicans began work on Christ Church in Cambridge, right next to Harvard College. Christ Church was a mission church, seeking to bring people into the Anglican faith. But, there were no Indians anywhere near the Church, only good Congregationalists. While Congregationalists thought it was all well and good to convert heathens or Catholics to Anglicanism, it was not appropriate to drag pious Congregationalists back into Anglicanism.

In 1762, the colony created its own Mission Society for the Indians, working to convert them to the Congregationalist faith. Back in England, the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury opposed this and got the Privy Council in London to disallow the Act in 1763. The colonists took this as an affront to their religion, which many in Massachusetts saw as a fundamental cornerstone of their society. The Anglicans in London were preventing the Congregationalists in Massachusetts from bringing their own local Indians to Christianity.

Adding fire to this dispute, the Anglican minister at Christ Church, Rev. East Apthorpe, decided to publish a pamphlet in 1763 supporting the Anglican Society’s missionary work in the colony. This drew a response from Rev. Jonathan Mayhew, the Congregationalist minister of West Church in Boston, who attacked Apthorpe for his derisive comments about Congregationalist Churches and claimed that Anglicans ministers were in Massachusetts to “spy out our liberty” and “help bring us into bondage.”

|

| Archbishop Thomas Secker (from Wikipedia) |

Around this same time, Secker decided this would be a good time to foist an Anglican Bishop on Massachusetts, and force the colony to pay for it. He had been planning this for some time and discussed his plans with members of Parliament. Leaders in Parliament sensibly thought it foolish to throw another controversy into the debate and put off the suggestion. Despite not even bringing it to a vote, word of the attempt reached Massachusetts and set off another round of concerns about Parliament’s power to get involved in colonial affairs.

The people of Massachusetts and New England generally, which was almost entirely Congregationalists, saw Britain, not only attempting to foist more officials on the colonies that would require higher taxes, but were interfering with the practice of their religion. Years later, John Adams wrote that fear of the plan to install an Anglican Bishop in Massachusetts “contributed...as much as any other cause to arouse the attention not only of the inquiring mind, but of the common people, and urge them to close thinking on the Constitutional authority of Parliament over the colonies.”

Colonial Trade

While religion and taxes were always touchy issues, trade laws affected how most colonists made a living, either directly or indirectly. Much of New England made its livelihood from the trans-Atlantic trade. Other colonies had large trade economies as well. Much of this was deliberate. Britain benefitted greatly from the raw materials imported from the colonies. Britain did not want the colonies to develop local self sustaining industries and economies. Rather, it wanted colonists to supply raw materials to Britain and buy finished goods from Britain. This provided jobs for the British people and provided the government with some revenue, primarily extracted at the ports in England.

Colonial trade had long been a simmering issue between London and the Colonies. Although trade restrictions and customs duties had been in place for more than a century, most people traditionally ignored them. British customs agents often lived in England and collected their pay without even seeing the harbors they were supposed to administer. Those who were on location often took bribes that allowed merchants to avoid most or all duties, as well as ignore restrictions on trade with other countries. Any customs agent foolish enough to try to enforce the law, could find himself in court, with a hostile jury forcing him personally to pay monetary damages to merchant traders.

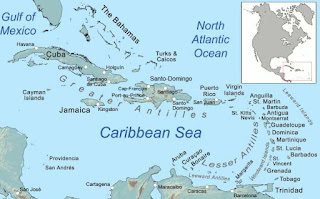

In the summer of 1760, Secretary of State William Pitt ordered colonial governors to crack down on trade with the enemy, which he saw as hampering the war effort. This was not just about tariffs going unpaid. This was more about New England ship captains engaging in trade with the same French colonies in the West Indies that the British were planning to invade. Such trade was giving direct aid and comfort to the enemy.

Outgoing Massachusetts Governor Thomas Pownall began to see his position as a career dead end. Getting the colonists to follow any British instructions seemed impossible. He left for England in June 1760 in pursuit of bigger and better jobs. Although he received an appointment to become Governor of South Carolina, he never went there, instead getting elected to a seat in Parliament. You may have already noticed this trend, but royal governors often had no specific affiliation with the colony the governed. It was quite common, even the norm, for royal governors to move from one colony to another and eventually back to England.

NJ Gov. Francis Bernard became the new Massachusetts Governor. Bernard decided to push Pitt’s initiative to crack down on illegal trade. It probably didn’t hurt that the Governor received a share of the proceeds of any ships seized in any smuggling. Even if Bernard had done everything else right, this highly unpopular enforcement of trade laws probably would have been enough to get the entire colony to hate him. But this was not his only misstep.

|

| Thomas Huthinson (from Wikipedia) |

Bernard probably thought he was giving a plumb job to a capable man who had been No. 2 for many years and was ready for advancement. Hutchinson came from a wealthy and prominent New England family. Improving relations with local colonial leaders helped make a royal governor more effective.

Hutchinson, though a capable politician, was not even a trained lawyer. More importantly, Governors Shirley and Pownall had both promised that the position of Chief Justice would go to James Otis, Sr. a prominent attorney who had served as the colony’s Attorney General and was a member of the Council of Massachusetts. When Bernard failed to follow through on the promises of his predecessors, James Otis, Jr. took Hutchinson’s appointment as a personal affront to his father.

Otis Jr., a lawyer in his own right, had been the Advocate General of the Admiralty Court, the prosecutor for cases involving smuggling, customs, and other trade violations. Otis immediately resigned his position and began representing merchants who were being prosecuted by the colony. Overnight, Otis went from being a member of the colonial establishment to one of its most outspoken opponents.

|

| James Otis, Jr. (from Wikipedia) |

In 1761, the Massachusetts surveyor general of customs applied for a routine renewal of his writs of assistance. These were general warrants that gave him the right to search any warehouses or homes for suspected smuggled goods. It was essentially a free pass to enter any private property and look for evidence of a crime, even without any suspicion that he would find anything. Otis opposed the writs in compelling arguments discussing the “natural rights of man” the tyranny and oppressive nature of such warrants, and how it was destroying their common law rights. His opposition received considerable publicity and made him a hero within the colony. It was enough for Chief Judge Hutchinson to write back to London for confirmation that such writs were legal. After receiving such confirmation, he issued the writs.

The people of Massachusetts, however, agreed with the arguments Otis had presented in opposition. Often goaded by merchants seeking to protect their goods, mobs formed to prevent customs officials from exercising their warrants. In an era when there were no police to back up officials and with no military around, customs officials had no choice but to back down.

The issue actually cooled off in early 1762 when the British captured Martinique and most of the other French colonies in the Caribbean. Suddenly it became perfectly legal for merchants to trade with these now British colonies and the issue went onto the back burner. But political battle lines had been drawn, and would return in later years. Colonists were showing they would openly defy laws that that they considered unjust or even simply against their interests. British officials also seemed to give colonists the confidence that if they stood up to something, officials in London would usually back down.

Next Week, the other big colonial issue, western lands, moves back to the top of the list as most of the major Indian tribes unite against the flow of British colonists threatening their land.

Next Episode 18: Pontiac's War

Previous Episode 16: Treaty of Paris & Wilkes Affair

Visit the American Revolution Podcast (https://amrev.podbean.com).

|

| Click here to donate |

|

| Click here to see my Patreon Page |

An alternative to Patreon is SubscribeStar. For anyone who has problems with Patreon, you can get the same benefits by subscribing at SubscribeStar.

Click here to go to my SubscribeStar Page

Further Reading

Websites

The Parson’s Cause trial of 1763: http://www.encyclopedia.com/law/law-magazines/parsons-cause-trial-1763

Parson’s Cause Speech: https://www.redhill.org/speech/parsons-cause-speech

The Parson's Cause, by A. Shrady Hill from Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church Vol. 46, No. 1 (March, 1977), pp. 5-35: http://www.jstor.org/stable/42973539 (free to read online with site registration).

Free online video lecture: Parson’s Cause Background by John Ragosta, University of Virginia: https://www.coursera.org/learn/henry/lecture/rJlxq/the-parsons-cause-background

Another video lecture on whether the Parson’s Cause speech was treason: https://www.coursera.org/learn/henry/lecture/N5vPz/the-parsons-cause-treason

Observations on the charter and conduct of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts; designed to shew their non-conformity to each other with remarks on the mistakes of East Apthorp, M.A. missionary at Cambridge, in quoting, and representing the sense of said charter, &c., by Jonathan Mayhew (1763): https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=evans;idno=N07403.0001.001

The Bishop Controversy, the Imperial Crisis, and Religious Radicalism in New England, 1763-74, by Peter Walker (2016) (New England Quarterly): http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/tneq_a_00623

The Critical Turn: Jonathan Mayhew, the British Empire, and the Idea of Resistance in Mid-Eighteenth-Century Boston, by Chris Beneke Massachusetts Historical Review Vol. 10 (2008), pp. 23-56: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25478696 (free to read online with registration).

Why the Colonies’ Most Galvanizing Patriot Never Became a Founding Father, by Erick Trickey

(2017) (James Otis, Jr.): http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/transformative-patriot-who-didnt-become-founding-father-180963166

James Otis Jr. biography: http://www.celebrateboston.com/biography/james-otis.htm

Free eBooks

(links to Archive.org unless otherwise noted)

Considerations on the Institution and Conduct of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, by East Apthorp (1763) (from Google Books).

The Barrington-Bernard Correspondence, by Edward Channing (ed) (1912).

The Anglican Episcopate and the American Colonies, by Arthur Cross (1902) (See, Chap. 6).

James Otis's Speech on the Writs of Assistance, by Albert Bushnell Hart (ed) (1902).

The Life of Thomas Hutchinson, by James Hosmer (1896).

A History of Newfoundland from the English, colonial, and foreign records, by D. W. Prowse (1895).

James Otis, the Pre-revolutionist: A Brief Interpretation of the Life and Work of a Patriot, by John Clark Ridpath (1898).

The Life of James Otis, of Massachusetts, by William Tudor (1823).

An Answer to Dr. Mayhew's Observations, by Thomas Secker (1764) (from Google Books).

The Constitutional Aspects of the "Parson's Cause", by Arthur Scott, Political Science Quarterly (1916).

Patrick Henry, by Moses Coit Tyler (1898).

The Life of Patrick Henry, by William Wirt (1903).

Books Worth Buying

(links to Amazon.com unless otherwise noted)*

Anderson, Fred Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766, Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

Knollenberg, Bernard Growth of the American Revolution 1766-1775, Liberty Fund, 1975.

Kukla, Jon Patrick Henry: Champion of Liberty, W.W. Norton & Co. 2017.

* As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.