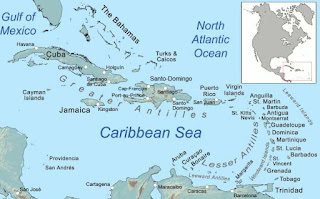

Last week, the British crushed the Cherokee uprising on the Carolina frontier. The new Bute Ministry also began picking off French and then Spanish colonies in the West Indies, all the while looking for some way to end the war before Britain drowned in debt.

Battle of Signal Hill

Although the war on the North American continent had essentially ended in 1760, Gen. Amherst would have one final tussle with the French in 1762.

With the French gone, other than small contingents in Louisiana and the Mississippi Valley, and with the British Navy preventing any cross Atlantic attacks, Amherst focused the bulk of his limited resources on the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes region, where Indians were likely to be his greatest problems. He also looked further west to Detroit and the Illinois valley, to make sure those western tribes were aware that France was gone forever and that they would be working with the British going forward.

As a result, a pacified region like Newfoundland had only a token force of about 300 regulars. In May 1762, a few French ships slipped past the British blockade. A force of about 800 French regulars landed on St. John’s in late June. The British garrison on the island was focused on preventing enemy ships from using the waters. When the French landed on the other side of the Island and attacked by land, they took the local garrison by surprise, and occupied Fort William relatively easily.

You may ask why the French bothered to land a few hundred troops without any support or hope of significant reinforcement given the continuing blockade. Certainly, 800 French troops were not going to retake Canada. Rather, the importance of holding the Island was to provide a basis for continuing to claim fishing rights in the North Atlantic. This was a major economic boon for France and one it did not want to relinquish when the war ended. The French realized they could not hold out if the British made any serious effort to reclaim the island. But if they continued to hold it when the treaty ending the war was signed, it would help to support their claim for fishing rights.

|

| Battle of Signal Hill (from Louvre Museum - Paris) |

Gen. Amherst’s own son Lt. Col. William Amherst led the British force, which landed in September. He was able to surprise the French by scaling cliffs on the seaward side of Signal Hill. A brief but bloody encounter ensued in what became known as the battle of Signal Hill. The British captured the high ground. From there, they began a bombardment of the Fort itself. The isolated French army surrendered after three days. The British once again held the island, captured the French force as prisoners, and eventually returned them to France.

This final battle with the French in North America was minor and the outcome virtually guaranteed. But the French incursion should have been a lesson about leaving small outposts who would be unable to defend themselves if trouble actually came.

The British Army Shrinks

After Gen. Jeffery Amherst’s armies had expelled the French from Montreal in 1760, he set about establishing military governments to maintain the newly conquered territories in Canada and the west. The British divided Canada into three military districts. Quebec remained under the command of Gen. James Murray, Trois-Rivières fell under the command of Col. Ralph Burdon. Montreal became command for Thomas Gage, who had been promoted to Brigadier General during the war.

In total, Amherst had about 16,000 regulars to maintain order in all of North America. In London, that seemed like too much. Almost immediately, London began reducing these numbers with instructions to deploy 2000 to the West Indies (the Caribbean) immediately and to plan for another 6000-7000 to be deployed in the fall for the planned invasion of Martinique. By the following year, cost cutting measures and demand for soldiers elsewhere, cut Amherst’s North American troop levels to below 8000 regulars. In order to maintain control of all the forts and outposts, Amherst would be forced to rely on colonial militia, which he had come to despise almost as much as the militia despised him.

|

| Gen. Jeffery Amherst (from Dictionary Canadian Biography) |

Another major problem was the supply of all the outposts. Military units from Pittsburgh to the Illinois Valley had to be supplied with food and other supplies. The cost of shipping that hundreds of miles was expensive. Amherst began permitting settlements around most of the forts and outposts. That way, local farmers and hunters could provide food to the outposts at more reasonable prices.

The settlements also provided an outlet for pressure in many colonies for western expansion. By controlling settlement to specific areas, Amherst hoped to avoid the problems of settlements popping up all over the place at random and causing problems. The settlements around forts provided crops and a local market for trade goods that benefited the garrisons. So, as long as everyone was satisfied with that and followed his orders, there would not be any problem, administrative costs would fall, and peace and order would prevail. Who thinks that’s going to happen?

Amherst continued to require more than 10,000 colonial militia to help maintain the forts and relieve regulars who were needed elsewhere in the Empire. Continued subsidies from London assured payment and the continued participation of militia in almost the numbers that Amherst requested. In both 1761 and 1762, the colonies, with the notable exceptions of Pennsylvania and Maryland, provided over 9000 men. Many served full year terms, allowing them to be used in fort garrisons far from home.

Even so, militia costs remained high. Without any immediate danger of invasion, most colonists wanted to get back to their lives, not perform garrison duty in some far off wilderness Fort.

Amherst continued to loathe the colonials. They rarely met enlistment quotas. They tended to show up late to relieve soldiers. They were, in his opinion, overpaid, and still managed to enrich themselves even more by embezzling supplies whenever given the chance. Even worse, colonial merchants continued to trade with the enemy. Trade with the French islands in the West Indies remained a profitable market for New England merchants. Amherst’s views were fairly common among British officers.

What the British never really appreciated was that colonists were not in the same desperate circumstances that many British peasants found themselves back in the British Isles. The abundance of land and rapidly growing number of towns and villages meant that most young men in America who were willing to make an effort could find themselves working their own farm or succeeding in some professional trade. In Britain, the lack of opportunity drove some young men to accept the miserable life of a professional soldier. Colonists had other options. If you wanted to enlist them, you needed to pay them enough to have recruits give up their other opportunities.

Treaty of Paris (1763)

Militia costs were only a small portion of the increasing war debt that drove the ministry to end the war as soon as possible. Despite the continuing British victories, Bute was determined to end the war. Throughout the spring and summer of 1762, Bute met secretly with the French Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Étienne-François de Choiseul, duke de Choiseul, offering quite generous terms to bring the war to an end. Only the King himself knew about the negotiations. When the negotiations became public, the rest of the government and the British public were outraged at how much Bute had offered to give away from the hard fought victories of the war.

|

| Duke de Choiseul (from Wikipedia) |

By November, 1762, Britain, France, and Spain had reached a preliminary treaty based on the Bute - Choiseul negotiations.

Britain had conquered the French colonies of Canada, Guadeloupe, Saint Lucia, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Tobago. It had also captured a number of the French trading posts in India, and along the African coast. It also captured the Spanish colonies of Manila (in the Philippines) and Havana (in Cuba).

France had captured the Island of Minorca in the Mediterranean as well as some British trading posts in Sumatra

Spain had captured the border fortress of Almeida in Portugal, and Portuguese colony: Colonia del Sacramento in modern day Uruguay.

|

| Changes in North American boarders - Treaty of Paris (from weebly) |

The Treaty permitted France to retain ownership of land claims west of the Mississippi. However, France had already ceded that territory to Spain in the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762. Even the French negotiators were unaware of the Treaty of Fontainebleau at the time they negotiated the Treaty of Paris. I’ve never read a definitive explanation as to why the French gave up that land. But maintaining a small strip between Spanish and English claims would be untenable and expensive in the long term, with no obvious economic benefit. Further, it may have been a continuing inducement to keep Spain in the war with England.

|

| Earl of Bute (from Wikipedia) |

Public opposition to the Treaty ran high in Britain. Bute was accused of giving away the hard won benefits of war. William Pitt had to be carried into the House of Commons on his sickbed to deliver a 3 ½ hour diatribe against the Treaty. Despite public opinion and Pitt’s opposition, the Treaty easily sailed through the House of Commons with 80% support and a voice vote in the House of Lords. The final Treaty went into effect in February 1763. A week later, Prussia and Austria entered their own treaty, which essentially gave each side what they had prior to the beginning of the war. So with all the paperwork done, what became known as the Seven Years War came to an end.

The Wilkes Affair

Before I end today, I want to touch on one final subject in England. It helps to underscore the deep divisions in England and introduces to a British radical who became a champion of in the Colonies during their fight for liberty.

As I mentioned, although the Treaty of Paris had swept through Parliament, it remained unpopular with the British public. It’s advocate Prime Minister Lord Bute also became the subject of public scorn. Still, the opposition needed a focal point from which to attack the ministry.

|

| Richard Grenville, Earl of Temple (from Wikipedia) |

After Pitt resigned from the ministry in 1761, his brother-in-law Richard Grenville, 2nd Earl Temple also resigned. Temple then decided to finance Wilkes as the editor of a newspaper called the North Briton. The newspaper was dedicated to attacking Bute personally, as well as all of his policies. In addition to its attacks on Treaty of Paris, the North Briton savaged Bute over his Cider Tax. This tax was a relatively minor but highly unpopular tax on cider production in England. Parliament had enacted it to help defray some costs of the war. But the public hated it, not only because of its cost, but because of the intrusion of tax collectors into their businesses.

Shortly after the Treaty of Paris concluded in 1763, Bute decided the public attacks, many of them from the North Briton, had become too much. He resigned as Prime Minister. The King, not happy about the resignation, grudgingly decided to make Temple’s brother, George Grenville, the next Prime Minister.

|

| The North Briton (from John Wilkes Club) |

The government brought charges of seditious libel against Wilkes and 48 co-conspirators, threw him in the Tower of London, and issued a general warrant to search for incriminating papers. Unlike a regular warrant, a general warrant permitted authorities to use their own discretion to decide who and what to search. There were virtually no limits to it. Overnight, Wilkes became a hero to the opposition condemning the attack on free speech, free press, and the use of general warrants.

Wilkes’ real saving grace though was that he was still a Member of Parliament. Members could only be prosecuted for a few limited crimes, such as treason. Seditious libel was not among them. After a week in the Tower, the court released Wilkes, who promptly brought a legal action for trespass against the Secretary of State, the Earl of Halifax, for issuing the general warrants.

However, the government was not done with Wilkes. Among the papers seized at his home was a work entitled “Essay on Woman” an obscene parody of Alexander Pope’s “Essay on Man.” Accused of blasphemy and pornography, Parliament began an action to expel Wilkes from his seat, after which time he could be prosecuted for his crimes. Wilkes fled to Paris before Parliament could complete the expulsion.

|

| John Wilkes (from Wikipedia) |

In 1768, he would return from exile, and was almost immediately reelected to Parliament. Still, eager to resolve the legal actions against him, Wilkes waived parliamentary immunity and was sentenced to two years and a £1000 fine. He then submitted a petition to the Commons complaining of illegality in the proceedings against him. On Feb. 3, 1769, the House of Commons expelled him once again, only to see him re-elected again on Feb. 15. The House then expelled him again, along with a resolution stating that he could not serve if elected again. Once again, voters elected him, but the House seated his opponent, being the candidate with the most votes who was eligible to serve in Parliament.

Wilkes continued to be involved in radical politics for decades, He was elected to numerous other offices, including Lord Mayor of London, where he played a minor role in publicizing the battles of Lexington and Concord, which I will discuss in a future episode. In 1774, he won another seat in Parliament, which finally decided to allow him to take his seat.

Wilkes became a hero to radical Whigs in Britain for his stand for free speech, against general warrants, and for the idea that voters should be permitted to choose their own representatives. His politics played particularly well in America where many of his positions, became political fodder for independence and eventually found their way into the US Bill of Rights.

Next week, I want to introduce three topics, the Parson’s Cause, where we first meet a young Lawyer named Patrick Henry, the Bishop’s controversy, where New England Puritans continuing dislike of the Church of England flares up, and growing colonial concerns over Britain’s renewed interest in enforcing trade tariffs.

Next Episode 17: Parsons Cause, Bishops, and Trade

Previous Episode 15: Anglo-Cherokee War, West Indies, and Spain

Visit the American Revolution Podcast (https://amrev.podbean.com).

|

| Click here to donate |

|

| Click here to see my Patreon Page |

An alternative to Patreon is SubscribeStar. For anyone who has problems with Patreon, you can get the same benefits by subscribing at SubscribeStar.

Click here to go to my SubscribeStar Page

Further Reading

Websites

Battle of Signal Hill: http://www.freedomsystem.org/battle-of-signal-hill

A contemporary account by Adm. Colville of the recapture of St. John’s. http://ngb.chebucto.org/Articles/colville-1762.shtml

Treaty of Paris, 1763 (full text): http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/paris763.asp

Milestones, Treaty of Paris 1763: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1750-1775/treaty-of-paris

The Treaty of Peace: https://www.britannica.com/event/Seven-Years-War/The-treaties-of-peace

John Wilkes: http://spartacus-educational.com/PRwilkes.htm

John Wilkes (1725-1798): http://www.historyhome.co.uk/people/wilkes.htm

The North Briton, Issue 45: http://www.constitution.org/cmt/wilkes/north_briton_45.html

Free eBooks:

(links to archive.org unless otherwise noted)

A Letter from a member of the opposition to Lord B------, (1763).

Reflections on the Terms of Peace, (1763).

Life of John Wilkes, by Horace Bleackley (1917).

Correspondence of William Pitt, Vol. 2, by William Taylor & John Pringle (eds) (1838).

Wilkes and the City, by Sir William Treloar (1917).

Biographies of John Wilkes and William Cobbett, by J.S. Watson (1870).

The North Briton, by John Wilkes (1764) (all issues of the paper in one bound volume).

The Life of William Pitt, Earl of Chatham Vol. 2, by Basil Williams (1914)

Books Worth Buying

(links to Amazon.com unless otherwise noted)*

Anderson, Fred Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766, Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

Cash, Arthur John Wilkes: The Scandalous Father of Civil Liberty, Yale Univ. Press, 2006.

Jennings, Francis Empire Of Fortune: Crowns, Colonies & Tribes in the Seven Years War in America, W.W. Norton & Co. 1988.

* As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.