The war with the French in North America had pretty much ended with the fall of Montreal in 1760. War continued to rage in Europe, Africa, and Asia though. Having secured North America, and with the British Navy dominating the Atlantic, William Pitt decided to hit the French even harder in the West Indies. But before he could do that, the British discovered that even a French Free North America still required some military attention.

The Cherokee War

The Cherokee were a fairly large tribe in the south. Generally, they had had relatively friendly relations with South Carolina, as they sat on the western frontier of the colony. Problems began to grow after a large number of Cherokee traveled up to Pennsylvania in 1758 to help Gen. Forbes capture Fort Duquesne. Back in Episode 12, I mentioned that Forbes had treated the Cherokee poorly. They ended up ditching him and heading home with the arms and ammunition he had provided to them. On the way back home, settlers in western Virginia accused the Cherokee of raiding their farms and taking property. Virginia militia ended up tracking down and killing at least 30 Cherokee warriors, scalping the Indians to exchange for reward money in Williamsburg.

|

| Gov. Sir William Lyttelton (from Wikipedia) |

Frustrated by South Carolina’s refusal even to hold serious talks over incursions on their land, angry Cherokee warriors started attacking isolated cabins on the border of Cherokee lands, killing around 30 frontier settlers that summer. In response, Lyttelton cut off all gun powder sales to the Cherokee. Since powder was critical to the tribe’s ability to hunt, they were divided on whether to go to all out war, or seek an accommodation.

In the fall of 1759, another group of moderate Cherokee leaders returned to Charleston to meet with the Governor and see if they could work out an agreement. Lyttelton responded by locking up the delegation, holding them hostage until the Cherokee turned over the warriors who had killed settlers over the summer. This essentially guaranteed war since Lyttelton had locked up all the moderate Cherokee leaders, leaving the war faction leaders in charge.

The Governor sent a large contingent of militia, with the Cherokee hostages, to Fort Prince George in Cherokee country. He demanded the tribes turn over for trial anyone who had killed any colonists before he would release the hostages. This was not going to happen. Cherokee responded by attacking more settlers, killing or capturing more than 100 over the winter. By January 1760, the militia terms were up and smallpox was beginning to ravage the Fort. Most of the militia went home, leaving a small winter garrison, with the hostages at the Fort.

|

| Sketch of Cherokee Country (from missedinhistory.com) |

Seeing the situation beginning to spin out of control, Lyttelton called for raising more troops to crush the Cherokee uprising. Then, in March 1760, he got an appointment to be Governor of Jamaica and left the mess for someone else to fix.

The Cherokee continued in open warfare along the South Carolina frontier. In addition to Fort Prince George, Indian raids attacked Fort Ninety-Six, Fort Dobbs and Fort Loudoun.

|

| Archibald Montgomery (from Wikipedia) |

The Cherokee warriors, however, never got the memo that the British had won. From the Cherokee perspective, they had driven the British from their territory. The Cherokee were still very much at war. They had besieged Fort Loudoun deep in Cherokee territory, in what is today Tennessee. In August, just as Montgomery’s expedition was setting sail for New York, the soldiers at Fort Loudoun agreed to surrender the Fort in exchange for safe passage back to Fort Prince George. The Cherokee allowed them out, but did not so much grant safe passage as much as a head start. A day later, the Cherokee chased down the retreating garrison and attacked them. The Indians killed about 25 soldiers including the Fort commander, who they scalped while alive and tortured to death. The Cherokee took the surviving 200 men as prisoners.

Despite their military success, the Cherokee were running drastically short on food and supplies, particularly ammunition. They could not get any neighboring tribes to ally with them, as they became more isolated over the winter of 1760-61.

|

| James Grant (from Clan Grant Society) |

For the next few months, Grant’s plan was to make the Cherokee feel the full wrath of the British military. Grant’s men burned any crops or buildings they could find. They took no prisoners, immediately executing any Cherokee who fell into their hands. In total, Grant destroyed at least 15 villages, an estimated 15,000 acres of Cherokee crops and an unknown number of people.

|

| Three Cherokee in London 1762 (from Wikipedia) |

The British essentially won, but the Cherokee had reminded them that they were a force to be respected. They could make life miserable for the colonists if they were pushed too far. Unlike the French, they were not going anywhere.

War moves to the Caribbean

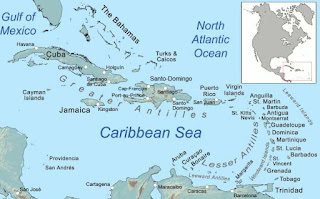

For the British, the Cherokee uprising was a minor distraction. Pitt wanted to put his focus on the West Indies, what we today call the Caribbean, where slave covered islands produced massive wealth in the form of sugar and spice. With the French Navy now in tatters, these French colonial islands made relatively easy targets.

In 1759, the British attempted a half-hearted attack on the French island of Martinique in the Caribbean. Martinique remained in French control, but the British did capture the nearby island of Guadalupe. After the destruction of the French Navy at Quiberon Bay, the British Navy had the upper hand and in 1761 captured the small island of Dominica.

While the small French garrison put up resistance, the British quickly overran them and took control of the island. Once the British took control, the civilians seemed content with the relatively generous terms of surrender. The French speaking inhabitants could continue to live as they had, speaking French and practicing their Catholic religion. They just had to swear loyalty to King George. After that, trade actually improved as they got access to other British markets to sell produce from their coffee plantations.

|

| West Indies, 1750 (from Kronoskaf) |

Robert Monckton, his wounds from Quebec now healed, led a detachment of 8000 regulars and American militia to Martinique in January 1762. By early February, Monckton’s forces defeated the French garrison and secured the Island for Britain. Soon thereafter, the British took St. Lucia, St. Vincent, Tobago, and Grenada. In each case, the locals willingly accepted their new government and benefited from trade within the British mercantile system.

More Political Changes in London

Pitt, however, would not lead Britain for the final stage of the war. Pitt’s increasingly aggressive war policies were in clear conflict with those of King George III, who wanted to wrap up the war as quickly as possible. The King wanted his own man in government, a Tory leader named John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute. In 1755, Bute had become the tutor for the future George III. The two became close confidants and political allies. The King saw Pitt and Newcastle as his grandfather’s men still pushing his grandfather’s policies. He wanted to replace them, but could not simply remove them while they were winning a popular war.

|

| John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute (from Wikipedia) |

Supporting the King’s view that the war needed to be ended, not expanded, was the ever increasing concern of cost. The national debt had risen to over £130 million, nearly double what it was at the beginning of the war. By modern measure, the debt was more than 150% of the entire British GDP. Lenders were becoming more reluctant to finance the debt with the Bank of England, and were demanding higher interest rates. With the war still bleeding millions each year, Newcastle was concerned that the slightest financial panic could bring down the whole economy. Newcastle had developed a good working relationship with Pitt over the past few years. So when Newcastle opposed Pitt’s plan for war with Spain, Pitt decided he was too isolated. In October 1762, Pitt tendered his resignation to King George.

With Pitt’s departure, the ministry needed a new leader for the House of Commons. They settled on George Grenville. Because Grenville was a political ally and brother-in-law to Pitt, it would not be apparent to Britain’s enemies how much this leadership change indicated a change in British resolve to continue the war effort. The British needed to appear willing to continue the war in order to ensure good terms in a final treaty. Grenville, however, would be more focused on getting the deficit under control and looking for an opportunity to end the war, even as Britain continued to take more enemy territory and prosecute the war on the continent.

|

| George Grenville (from Wikipedia) |

Aside from being a Tory, Bute was an outsider to English politics. He was a Scot by birth and upbringing. His family was not closely tied into the London establishment. His only grasp on power was his close relationship with the King.

Nevertheless he shared the King’s view that Britain needed to wrap up the war and get its debt under control. Bute advised Prussian King Frederick (later called Frederick the Great) to wrap up his war with Russia and Austria as Britain wanted to close the spigot of military aid. Frederick essentially told him to buzz off, and this is literally what he said: “Learn your duty better, and take note that it is not your place to proffer me such foolish and impertinent advice.”

After that slam, Bute actually reached out to the enemy, the new Russian Czar Peter III, asking him to keep his troops in the field against Prussia in order to force Federick into peace negotiations. Peter, despite being at war with Prussia, was actually an admirer of Frederick. Peter ended up sending Bute’s note to Frederick who then had even more reason to loathe a supposed ally who was corresponding with the enemy against him. Any possibility there might have been for a working relationship between Bute and Frederick was now completely dead. Czar Peter’s Prussian fetish did not win him any friends at home though. A few months later his own wife, Catherine (later Catherine the Great) overthrew her husband and renewed Russia’s war against Prussia.

Despite having a King and a Prime Minister who wanted to end the war quickly, actually ending the war was proving impossible. Pitt’s policy of capturing more colonies around the world was rolling on its own momentum. It’s pretty hard politically to tell your armies and navies to stop winning so much. Other European powers now began to fear that the British Empire would soon come to dominate the continent.

Spain Joins the War

By this time, France knew it was in serious trouble of permanently losing valuable real estate around the world. King Louis finally convinced his cousin, King Charles III of Spain to enter what was called the “Family Compact” in August 1761 promising support for France in its war with Britain. While still officially neutral, Spain promised to enter the war if not over by May 1762.

As I mentioned, Pitt had gone nuts over this agreement and wanted to go to war in the fall of 1761. The government refused and he ended up resigning over the issue. Despite Pitt’s departure in October, by November the new administration sent an ultimatum to Spain demanding that Spain declare it would not ally itself with France in the war, or Britain would consider the two countries at war. Having heard nothing, Britain declared war on Spain on January 4, 1762. By the time Spain responded with its own declaration on Jan. 18, British ships were already en route to take Cuba, and London had sent orders to India to dispatch a British force to take the Philippines. So rather than wrapping up the war as hoped, the British added a new enemy combatant and opened up several more sections of the world for battle.

Spain invaded Portugal in May, obliging the British to provide troops for its ally’s defense. A British force in Portugal led by Lord Loudoun, who had failed in North America years before, led an effective defense against the Spanish assault on Lisbon. A daring young Brigadier named John Burgoyne helped by destroying several Spanish supply bases. Burgoyne had the capable assistance of a highly effective newly promoted Lt. Col. named Charles Lee, who had fought at Fort Carillon a few years earlier. Remember both of those names as we will see them again in a few years.

While the British fought Spain to a stalemate in Portugal, another force of 12,000 descended on Havana Cuba. Havana was the hub of the Spanish colonial system in America. Britain controlled the Atlantic, but the fortress defenses to Havana Harbor were impregnable to any fleet. As a result, the British force had to land several miles away, and assault Havana by land.

|

| The Capture of Havana 1762 (from Wikimedia) |

By late July, 4000 more reinforcements arrived from North America. About half were regular army and half were colonial militia. By mid-August, Havana had fallen to the siege. But the tropical diseases continued to take their toll. Nearly half of the invading British force succumbed to disease. Fortunately for the British, Cuban civilians accepted the new government under generous surrender terms that allowed them to carry on with their lives as before, and to take advantage of new access to British trading partners. It appeared that Britain had put another large and valuable colony into its empire.

Next week: Britain finally ends the war with the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

Next Episode 16: Treaty of Paris & Wilkes Affair

Previous Episode 14: Canada Becomes British & Britain Gets King George III

Visit the American Revolution Podcast (https://amrev.podbean.com).

|

| Click here to donate |

|

| Click here to see my Patreon Page |

An alternative to Patreon is SubscribeStar. For anyone who has problems with Patreon, you can get the same benefits by subscribing at SubscribeStar.

Click here to go to my SubscribeStar Page

Further Reading

Websites

The Cherokee War: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/America/United_States/North_Carolina/_Texts/LEEIWNC/12*.html

French and Indian War in the Carolinas: http://www.carolana.com/NC/Royal_Colony/french_indian_war.html

Outacite Ostenaco and the Cherokee-Virginia Alliance in the French and Indian War, by Douglas Wood: https://textbooks.lib.wvu.edu/wvhistory/files/html/02_wv_history_reader_wood

Fort Prince George: https://sites.google.com/site/pickenscountyhistoricalsociety/fort-prince-george

British Expedition against the Cherokee, 1760: http://www.kronoskaf.com/syw/index.php?title=1760_-_British_expedition_against_the_Cherokee_Indians

British Expedition against the Cherokee, 1761:

http://www.kronoskaf.com/syw/index.php?title=1761_-_British_expedition_against_the_Cherokee_Indians

The Two Battles of Echete Pass, by Richard Thornton (2017): https://peopleofonefire.com/the-two-battles-of-echete-pass-forgotten-but-dramatic-events-during-the-french-and-indian-war.html

Seven Years War in the Caribbean: http://caribya.com/caribbean/history/seven.years.war

British Expedition against Domenica, 1761: http://www.kronoskaf.com/syw/index.php?title=1761_-_British_expedition_against_Dominica

British Expedition against Martinique, 1762:

http://www.kronoskaf.com/syw/index.php?title=1762_-_British_expedition_against_Martinique

British Expedition against Cuba, 1762: http://www.kronoskaf.com/syw/index.php?title=1762_-_British_expedition_against_Cuba

Pitt the Elder Resigns: http://www.historytoday.com/richard-cavendish/pitt-elder-resigns

Free eBooks:

(links to archive.org unless otherwise noted)

The Cambridge Modern History, Vol 6, by John Acton, et al (1902) (discusses Pitt’s departure from office, Spain’s entry into the war, and other details of the Seven Years War).

William Pitt Earl Of Chatham, by Arthur Innes (1907).

Some Observations on the Two Campaigns Against the Cherokee Indians, in 1760 and 1761, by Philopatrios (1762).

Books Worth Buying

(links to Amazon.com unless otherwise noted)*

Anderson, Fred Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766, Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

Greentree, David A Far-Flung Gamble: Havana 1762, Osprey Publishing, 2010.

Hatley, Tom

The Dividing Paths: Cherokees and South Carolinians Through the Era of Revolution, Oxford Univ. Press, 1993.

Jennings, Francis Empire Of Fortune: Crowns, Colonies & Tribes in the Seven Years War in America, W.W. Norton & Co. 1988.

Oliphant, John Stuart

Peace and War on the Anglo-Cherokee Frontier, 1756-63, LSU Press, 2001.Tortora, Daniel J. Carolina in Crisis: Cherokees, Colonists, and Slaves in the American Southeast, 1756-1763, Univ. of NC Press, 2015.

* As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

No comments:

Post a Comment