I know I mentioned last week that I was going to cover the Penobscot Expedition this week. However, I’m going to push that off until next week so that I can cover this week, the story of Fort Laurens, which chronologically, I probably should have covered a few episodes back.

Fort Laurens was a western outpost, about 80 miles west of Pittsburgh, in modern-day Ohio. It was built as part of an effort to capture British-held Detroit.

Lachlan McIntosh

This effort was led by General Lachlan McIntosh, who I last talked about back in Episode 138. The general from Georgia had faced continual frustrations in his efforts against British-controlled East Florida. Much of his frustration came from the leaders of Georgia, and North and South Carolina, who refused to recognize Continental authority over State militia. As a result, McIntosh could never mount a successful military mission in the south.

The disputes with civilian leaders had boiled over in May of 1777 when Georgia President Button Gwinnett arrested McIntosh’s brother and tried to cut McIntosh out of the chain of command. McIntosh killed Gwinnett in a duel. Several months after that, General Washington transferred McIntosh up north, where he would not be subject to revenge attacks by other men in the Gwinnett faction.

McIntosh spent the winter at Valley Forge with the rest of the army. Washington then gave him an independent command in Pittsburgh. Initially his task was to launch an offensive against British-held Detroit. But rather quickly his task took a less ambitious goal of simply trying to keep the Indian tribes in the Ohio Valley from rising up against the Americans.

The Squaw Campaign

In the months before McIntosh’s arrival in Pittsburgh, the situation with the native tribes had taken a turn for the worse. That prior winter, Colonel Edward Hand had command of the small frontier force at Fort Pitt. In an attempt to quell a possible native attack being organized by British Governor Henry Hamilton in Detroit, Hand organized a group of several hundred militia. His goal was take out a cache of weapons provided to Seneca and Cayuga warriors for a spring campaign.

Since Hand did not have a significant force of Continentals, he had to raise a force of local militia. Hand wrote about his goals in a letter to Virginia Colonel William Crawford, who he hoped could help to raise soldiers for the campaign:

As I am credibly informed that the English have lodged a quantity of arms, ammunition, provision, and clothing at a small indian Town, about one hundred miles from Fort Pitt to support the savages in their excursions against the inhabitants of this and the adjacent counties, I ardently wish to collect as many brave, active lads as are willing to turn out, to destroy this magazine. Every man must be provided with a horse, and every article necessary to equip them for the expedition, except ammunition, which, with some arms, I can furnish.

Colonel Hand's recruitment efforts raised about 500 Pennsylvania and Virginia militia from the region . He set out after the enemy’s cache of arms. Rain and melting snow had flooded most of the area’s rivers, and had turned much of the land into a swampy mush. He marched his men about 40 or 50 miles up the Beaver River. The conditions made marching so slow that Hand quickly realized he would run out of supplies before they reached their target. He ended up calling off the mission, turned his men around and marched back toward Pittsburgh.

|

| Edward Hand |

On the return march, several scouts reported finding a small gathering of 50-60 Indians nearby. They reported that these were likely Cayuga warriors gathering for an attack on nearby settlements. The militia attacked the native camp.

As it turned out, they were not warriors preparing for an attack. They were not even members of a hostile tribe. They were members of the Lenape, also known as Delaware, tribe. The leader of the group was known only as “Pipe”. When the militia attacked, Pipe put up a defense, while telling his family, consisting of his wife, mother, and children to make a run for it. The militia killed Pipe, then chased down his family and massacred them as well. They interrogated several prisoners and learned of another Indian gathering a few miles away. The militia set out after that group, only to find about ten women and children collecting salt. Most of them scattered, but the militia managed to run down and kill several women and at least one child from that group as well.

The militia returned to Fort Pitt with the scalps of their victims, along with two female prisoners. Female Indians were known as squaws at the time, so that the mission became known as the squaw campaign. The campaign’s commander, Colonel Hand expressed “mortification” at the killing of women and children. The leadership considered the entire campaign to be an embarrassing failure.

For the local Delaware Indians though, this was more than an embarrassment. It was a massacre of innocent people just going about their lives. The most prominent Indian killed, Pipe, had been reputed to be friendly to the American cause and had been instrumental in keeping the Delaware neutral.

Following the killing of him and his family, the Delaware became decidedly more hostile, led by Pipe’s brother, known as Captain Pipe, or Hopocan.

Treaty of Fort Pitt

General McIntosh arrived at Fort Pitt only a few months after the Squaw Campaign. It’s unclear if McIntosh replaced Colonel Hand because of the massacre. But Hand was never sanctioned for his actions and went on to be promoted to general later in the war. It seems more that McIntosh’s deployment was part of a larger effort to launch an offensive against British-held Detroit.

McIntosh had the difficult task of making peace with the Delaware Indians, who were related to the people who had been massacred only a few months earlier. Now you may ask, why would Indians whose relatives were just victims of a massacre be willing to work with those same people? Well, for one thing, the “people” had changed. Edward Hand was no longer in command, and the local militia were no longer the primary military force. General McIntosh had brought with him about a thousand Continental soldiers to support his offensive against Detroit.

|

| Fort Pitt |

Up until this time, the Delaware had remained neutral. Traditionally the Iroquois had negotiated treaties with the colonists on behalf of the Delaware. But the Iroquois Confederation was itself divided by this war and was no longer an effective body for diplomacy. The Delaware neutrality essentially meant that neither side would be permitted to enter their territory without being attacked. Since this area had not been a particularly contentious piece of real estate, that policy had not really been challenged up until this point. But since Gen. McIntosh was going to have to travel through Delaware territory to reach Detroit, he needed to reach an arrangement with the local tribes.

The native contingent that met with General McIntosh at Fort Pitt included three chiefs: White Eyes, John Killbuck, Jr., and Captain Pipe, whose mother and brother had been killed and scalped in the Squaw Campaign. These chiefs wanted assurances that if they permitted the Continental Army to march through their lands on the way to Detroit, that the army would protect the Delaware from any British reprisals, and that the army would also provide some law enforcement to prevent settlers or militia from attacking the Indians again.

The American negotiators agreed to these terms. They even discussed the idea of turning the Ohio Territory into a 14th state in the Union, with the Delaware as the leaders of that state. Of course, such a step would require the approval of the Continental Congress, but that might be possible.

The result of the negotiations was the Treaty of Fort Pitt in September, 1778, granting the Continental Army access to the Ohio Valley.

Simon Girty

Ironically, while the Delaware Indians made a deal with the same side that had just attacked and murdered their women and children, one of those attackers was moving in the other direction. A man by the name of Simon Girty had served as a scout and a translator on the Squaw Campaign.

|

| Simon Girty |

Although the family managed to make a living through farming and trading with local Indians, eastern land speculators claimed that Girty was illegally squatting on land that they owned. The agent for the land owners, George Croghan, burned the family farm, and had the sheriff throw the family into the street.

The end of Girty’s father is a matter of contention. One story says that Girty then fought a duel in which he was killed. Another says that an Indian killed Girty in a tomahawk attack. In either case, the elder Girty was killed, leaving young Simon without a home or a father at age nine.

His mother married a man named John Turner, who had established his own farm, and raised Girty and his brothers as their new stepfather. In the story where Girty was killed by an Indian, the story also says that Turner killed that Indian in revenge, before marrying Girty’s widow.

In 1754, when Girty was 13 years old, George Croghan, the same man who had the Girtys thrown off their farm, joined up with a Virginia militia colonel by the name of George Washington in the Ohio Valley. They killed some French soldiers there, starting a massive war. The French, and their Indian allies made war all along the colonial frontier, attacking settlements.

Turner took his family to Fort Granville for protection. He joined the local militia and served as a sergeant. In 1756, the fort commander went out on a patrol. The patrol was ambushed and killed by a group of about 50 French soldiers and 100 Delaware Indians. The French and Indian force then demanded the surrender of Fort Granville. Sergeant Turner, then the most senior official at the fort, agreed to surrender and opened the fort’s doors to the attackers.

The attackers burned the fort and took the inhabitants as prisoners. Sergeant Turner was condemned to be tortured and burned at the stake. The Delaware burned and cut him for over three hours before someone put a tomahawk into his skull, thus finally ending his misery. All of this was done with his wife and children, including Simon Girty, watching all of these events unfold.

The fifteen year old Girty was then separated from his mother and brothers, sent to live with the Mingo Chief Guyasuta. The Mingo were part of the larger Seneca tribe, then living in what is today western New York and Pennsylvania. Guyasuta was the head of a village near the current town of Erie, Pennsylvania. There, Girty became part of the tribe, learning the language and culture of the people who had adopted him.

Guyasuta had actually accompanied George Washington on one of his early forays into the Ohio Valley. But once war broke out, Guyasuta sided decidedly with the French. It is believed that Guyasuta’s warriors played a role in attacking General Braddock’s forces on the Monongahela, and also took part in an attack on a British force led by General James Grant. Grant was part of the larger Forbes Expedition to capture Fort Duquesne, on the site of what became Pittsburgh. After the French gave up and left North America, Guyasuta continued the fight against the British, taking an active role in Pontiac’s War.

It is unclear if Girty was an active warrior, fighting under Guyasuta on these campaigns. He did not discuss this later in life. However, being a young man in this twenties, and an adopted member of the tribe, he very likely did participate. Following the end of Pontiac’s rebellion, the British demanded the return of all colonists held by the Indians. Girty had spent more than seven years with the Mingo, but was returned to the British as part of this agreement.

Girty’s familiarity with both colonial and Seneca culture served him well. He found work as a translator at the negotiations for the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768. Following the French and Indian War, Girty continued to live on the frontier, in what was official Indian territory, and in defiance of the British Proclamation of 1763. He mostly made a living as a fur trader. He was decidedly living with other colonists though, including men like George Rogers Clark, Daniel Boone, William Crawford, and Daniel Morgan.

During Lord Dunmore’s war, Girty served as a scout for the Virginians and received a commission as a lieutenant in the Virginia militia. Later, Girty served as a scout and a translator around Fort Pitt and joined what became the Squaw Campaign in that capacity.

During that campaign, the massacre of native women and children had a profound impact on Girty. He left the area shortly after the campaign ended. He traveled to Detroit and offered his services to the British.

Fort Laurens

Meanwhile back at Fort Pitt, General McIntosh, having completed his treaty with the Delaware, began to establish the Continental presence in the region. He first established Fort McIntosh, about 25 miles down the Ohio River, northwest of Fort Pitt.

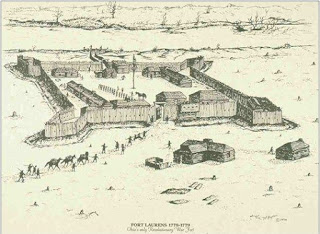

In late 1778, McIntosh built Fort Laurens, named after then-President of Congress Henry Laurens. The fort was about 80 miles west of Fort Pitt, in present-day Ohio. By December, the log fort was completed enough for winter quarters. Because of the difficulties in getting supplies to the fort, McIntosh took the bulk of his army back to Fort Pitt and Fort McIntosh for the winter. He left Continental Colonel John Gibson, commanding a garrison at Fort Laurens of less than 200 men.

McIntosh realized over the winter that marching a large force through hundreds of miles of wilderness was going to be difficult, to say the least. He needed more than safe passage from the local Indians. He needed their active support on the campaign. He called on the Delaware to join the campaign against Detroit, and threatened them with loss of land if they refused to help. If the tribes complained that that was not part of their deal in the treaty, I think McIntosh’s response was something like I am altering the deal, pray I do not alter it further. This turned the local tribes against the Americans, and made them more disposed to favor the British.

|

| Fort Laurens |

In January, 1779, Simon Girty returned to help coordinate these attacks. After hitting several supply wagons, Girty returned to Detroit for more reinforcements. On February 22, he returned with enough men to begin a full siege of the fort. It began when the fort garrison sent out a work detail of 19 men to collect firewood. The loyalist and Indian force ambushed the work detail, then executed and scalped all of the men in view of the fort walls.

Over the next month, the garrison began to freeze and starve as they could not collect wood or food. Back at Fort Pitt, McIntosh got word of the attack and assembled a force of 500 soldiers to relieve the fort and to wipe out the attackers. The relief force arrived on March 23. On seeing their arrival, the garrison fired their guns in celebration. The gunfire managed to spook the horses carrying supplies, causing them to run off into the woods just as it was getting dark. As a result, the relief column lost most of its own food supplies.

Without sufficient food, McIntosh thought that he could not continue the winter campaign against a foe who would simply hide in the woods and ambush at will. McIntosh opted to return to Fort Pitt, leaving a new garrison of just over 100 men, along with sufficient supplies for the next few months so they would not have to leave the fort. The Indians kept up their attacks on anyone trying to leave or approach the fort.

At the same time, larger events were favoring the Americans. Over that same winter, George Rogers Clark asserted American control of the Kentucky and Illinois territories and even captured the British Governor Henry Hamilton, who had left his headquarters at Detroit. In New York, the Americans were beginning the Sullivan Campaign, which I will discuss in a few weeks, which would cripple the pro-British Iroquois as a major threat.

By the summer of 1779, McIntosh requested to be transferred back south, to take part in the fight to recapture Georgia from British occupation. Colonel Daniel Brodhead took command of the forces at Fort Pitt. Broadhead decided that Fort Laurens was only a liability. He took a large column to relieve the garrison and return all the men back to Fort Pitt. In August, the Continental finally abandoned Fort Laurens, and marched back to Fort Pitt, suffering several minor Indian attacks on their return back to Pittsburgh - just to remind them they were not welcome there. That was the end of Fort Laurens.

Aftermath

Simon Girty and several of his companions were labelled as traitors and had rewards put on their heads for their capture. Girty would continue to fight for the British for the remainder of the war. In October of 1779, he led a raid into what is today Kentucky. There, he ambushed a group of Continental soldiers under the command of Colonel David Rogers, killing or capturing almost the entire 70 man unit.

While the Americans would make more minor forays into what is today Ohio, Fort Laurens was the only attempt to create a permanent presence in that region. The area would remain under the control of the British-allied Delaware Indians through the end of the war.

- - -

Next Episode 228 Penobscot Expedition

|

| Click here to donate |

|

| Click here to see my Patreon Page |

An alternative to Patreon is SubscribeStar. For anyone who has problems with Patreon, you can get the same benefits by subscribing at SubscribeStar.

| Help Support this podcast on "BuyMeACoffee.com" |

Signup for the AmRev Podcast Mail List

Further Reading

Websites

“From George Washington to Brigadier General Lachlan McIntosh, 26 May 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-15-02-0230

“To George Washington from Brigadier General Lachlan McIntosh, 7 June 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-15-02-0358

General Edward Hand: The Squaw Campaign https://emergingrevolutionarywar.org/2018/03/09/general-edward-hand-the-squaw-campaign

Life and Myth of Simon Girty https://www.heinzhistorycenter.org/blog/fort-pitt-museum/life-myth-simon-girty

Simon Girty: http://friendsofthefrontier.org/page/Simon-Girty.aspx

Simon Girty: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/girty_simon_5E.html

Burke, Mike The Delaware Treaty of 1778, Sept. 26, 2018 https://www.heinzhistorycenter.org/blog/fort-pitt-museum/delaware-treaty-1778

Sterner, Eric “The Siege of Fort Laurens” Journal of the American Revolution, Dec. 17, 2019 https://allthingsliberty.com/2019/12/the-siege-of-fort-laurens-1778-1779

Fort Lauren Museum: https://www.fortlaurensmuseum.org/ourhistory.html

Simon Girty War Party: https://www.nkytribune.com/2016/02/our-rich-history-revolutionary-war-forces-suffered-defeat-in-nky-thanks-to-simon-girtys-war-party

Free eBooks

(from archive.org unless noted)

Boyd, Thomas Simon Girty, The White Savage, New York: Minton, Balch & Co. 1928.

Butterfield, Consul Willshire History of the Girtys : being a concise account of the Girty brothers--Thomas, Simon, James and George, and of their half-brother John Turner, Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co. 1890 (1950 reprint).

McKnight, Charles Simon Girty : "The White Savage"; A Romance of the Border, Philadelphia: J. C. McCurdy & Co. 1880.

Ranck, George Washington Girty, the White Indian, Fort Wayne: Prepared by the staff of the Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen County, 1955.

Thwaites, Reuben Gold (ed) Frontier defense on the upper Ohio, 1777-1778, Madison, Wisconsin historical society, 1912.

Books Worth Buying

(links to Amazon.com unless otherwise noted)*

Butts, Edward Simon Girty: Wilderness Warrior, ReadHowYouWant, 2017

Gidney, James B. & Thomas I. Pieper Fort Laurens, 1778-1779: The Revolutionary War in Ohio, Kent State Univ. Press, 1976. Also read on archive.org.

Hoffman, Phillip W. Simon Girty Turncoat Hero, American History Press, 2008.

* As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

No comments:

Post a Comment