When we last left the Howe brothers in Episode 150. They had loaded up their army aboard hundreds of ships and sailed off from New York out into the Atlantic Ocean in July 1777. For several weeks no one was quite sure where they were going until the British landed at Head of Elk, Maryland (today Elkton). To get there, the fleet had to sail to the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, past Norfolk Virginia, then back up through the bay, into the Elk River before finally landing. The fleet led by Admiral Richard Howe in the HMS Eagle, skipped the traditional landing areas, moving up muddy bottomed rivers, to find a remote site as far up the waters as the ships would go.

The Eagle Has Landed

In the very early pre-dawn hours of August 25, 1777 the British Army began to disembark at Head of Elk. In order to surprise the Americans, Howe had avoided the well-defended Delaware Bay. He had also avoided all of the established ports in the Chesapeake that would have made the landing much easier.

Head of Elk was a tiny hamlet without a large port. The water in the area was shallow and muddy. The British ships of the line could not simply pull up to a port and disembark their soldiers. The weary men, who had been stuck aboard ship for six weeks, had to climb down onto smaller boats to row ashore. Much of the army unloaded at Turkey Point, a small ferry on the Elk River. The process of moving more than fifteen thousand soldiers ashore, along with their equipment, was a slow and tedious process. The Howe brothers were fortunate that the Americans did not confront them at the landing site. Fighting a battle while disembarking could easily have become a nightmare for the British. The ships were also vulnerable with no room to maneuver.

|

| British Fleet offloads at Turkey Point |

By the end of the second day, Tuesday, most of the army had unloaded, including all the horses. More than half of the 320 horses that had been loaded onto ships in New York and died before the Maryland landing. Poor food and conditions made survival difficult. Many of the horses still alive would need time to recuperate. Many of the soldiers were not in much better shape. Twenty-seven soldiers had died during the six week voyage, and many more were sick. Even for those not bed-ridden, weeks of poor conditions below deck with meager rations meant that they needed time to recover. It would still be several more days before all the arms and equipment, including the tents for the soldiers, would be unloaded.

To make things worse for most of the soldiers, who did not yet have their tents, a terrible rain soaked the men. They had to scrambled to build crude shelters for themselves. A large amount of British gunpowder was also water damaged.

The trip to Maryland from New York had required the men to remain on board for as long as a typical cross Atlantic trip from Britain usually took. For all of that effort, the British army still faced about a fifty mile march to Philadelphia. Three months earlier, the British army had encamped in Brunswick, New Jersey, only sixty miles northeast of Philadelphia. When they were in New Brunswick, the Continental Army was behind them and nothing stood between the British and Philadelphia. Now that they had moved to Maryland, Washington had time to move his army into position to defend the city.

Americans Meet the Enemy

General Washington had received word that the British were in the Chesapeake preparing to land about two days before the actual landing. He had marched his Continental Army through Philadelphia on their way to the south in order to meet the enemy.

|

| British route of attack (from Brandywine Battlefield) |

That evening, Washington held a council of war with some of his top officers to decide whether they should attack the following day, or wait. Our source for the meeting comes from a British officer who got the information from an aide of another officer who had attended the meeting, so third-hand information. But according to that source, the French and German officers argued that they should strike right away while the British were still getting unloaded. The American officers counseled to wait. They needed to find out exactly what strength they were facing, continue to gather their own forces, and preferably force Howe to attack the Americans at a location of the American’s choosing.

Washington agreed to wait on any attack. The next morning, August 26, General Washington set out personally to reconnoiter the enemy. With him were General Greene, the Marquis de Lafayette, and a new brigadier general, George Weedon.

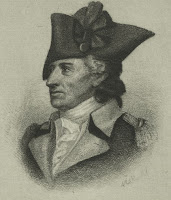

George Weedon

Back in Episode 131, I mentioned that congress had appointed a whole pack of new generals, including nine brigadiers in one day. One of those new appointees was George Weedon. Since this is the first time I’ve had cause to mention him, I’ll give him a short introduction.

|

| George Weedon (Wikimedia) |

Weedon was an outspoken patriot at his tavern. One English traveler noted that Weedon was “very active and zealous in blowing the seeds of sedition.” In 1774, he and Mercer formed an independent militia company of patriots. Once the war began, Weedon took a commission as a lieutenant colonel in the Third Virginia Regiment which soon was incorporated into the Continental Army. In the first year of the war, Weedon’s regiment remained in Virginia, defending attacks led by Royal Governor Lord Dunmore. When the Continentals moved to New York, Weedon’s regiment joined them.

Weedon distinguished himself, participating in the crossing of the Delaware. Washington put him in command of moving the Hessian prisoners back to Pennsylvania after the battle of Trenton. As part of Congress’ plan to greatly enlarge the Continental Army following the Princeton victory, Weedon received his commission as brigadier general.

Scouting the British

Washington’s small company reached a hill about two miles from the enemy camp, where they could view the British. That afternoon, a terrible rain storm caused the generals to take shelter in a nearby farmhouse, where they spent the night. Everyone agreed that it was a great risk. If an informer word got back to the British that Washington was nearby without his army, it would have been an easy step to capture him, much like they had done to Charles Lee the previous year. Washington’s luck held out though. His small troop left at dawn the following morning and rode back to the American lines. Later that day, General Howe set up command in the same house. There is also a story that both General Howe and General Washington at one point spotted each other both on hills about one mile apart, both men carefully watching the other.

Over the next few days, both armies continued to consolidate and maneuver. The British and Hessian scouts scoured the area for supplies and friendly locals. General Washington continued to survey the land personally, looking for ground to set up a proper defense, as well as figure out exactly what path the British army might take.

|

| Village of Wilmington, DE (from Soc. of Cincinnati) |

Such a large scale raid across the farms and villages to the west of Philadelphia would have made the landing in the Chesapeake Bay much more sensible. Otherwise, why didn’t Howe simply march across New Jersey? That would have been much faster and forced the same sort of confrontation with Washington’s Continentals. Washington also feared a possibility that the British might try a two pronged attack, with Howe moving on Philadelphia from the south While General Henry Clinton marched a second British Army out of New York City to attack Philadelphia from New Jersey. It was even possible that General Burgoyne might march through New York in time to join up with a final three-pronged push on Philadelphia.

British Advance

In truth, the British did not even seem sure of exactly what they would do next. General Howe left a few regiments at Turkey Point to defend the fleet as it slowly made its way back out to the Chesapeake. General Howe and Admiral Howe agreed that the fleet would sail back to the Delaware Bay and up the Delaware River where the army and navy would meet again at New Castle, Delaware. But as we will see, that never happened. British officers complained that they had no maps of the area and no intelligence about the enemy or the locals. Since the few horses they had were too sick to ride, they had no cavalry to reconnoiter the area. Hopes of attracting many local loyalists to assist the army quickly faded.

Despite these setbacks, the British had no choice but to move forward. Even before the entire British Army had made it to land, the British began to explore the area around them. Some of the first troops off the ships were Howe’s best light infantry, grenadiers, and Hessian jaegers. The soldiers began to scout the area for miles around, looking for food and forage. They also prepared to meet with local Tories, who they were told were common in the area. However, they found most of the land abandoned. Much of the area was still an unsettled wilderness. Locals had largely abandoned the region, going into hiding.

General Howe had issued strict orders to prevent his soldiers from marauding the region. A key part of his plan was returning the King’s peace to the region and convincing people so disposed to support the regulars in their efforts to reclaim the region. On August 27, two days after the landing began, Howe published another one of his declarations offering pardon to any rebels who surrendered and took an oath to support the King.

Howe’s hungry soldiers were more concerned about finding food. They did capture some abandoned farm animals, and also hunted the abundant wildlife in the region. Some of the Hessian jaegers reported good hunting, but so much effort without rest after leaving the ships resulted in several of them dying from heatstroke.

They were also interested in plunder. As Captain John André put it, “There was a good deal of plunder committed by the Troops, notwithstanding the strictest prohibitions.” One soldier was accused of chopping off the fingers of a local woman in order to steal her rings. General Howe issued orders to execute any soldier found leaving camp without orders or found with plunder.

Howe’s orders to execute his own soldiers for plundering was not the only concern for British and Hessian soldiers. On August 31, one officer recorded that his men had found two regulars on the side of the road with their throats slit. Two other grenadiers were found hanged. In each of these cases the victims were believed to have been plundering people’s homes. None of this seemed to discourage continued attacks on whatever small villages or isolated farms that the armies could find. One British officer in a letter home noted the pervasive and shocking level of plundering. In his letter, he expressed concern that someday these lawless British soldiers might return home and be unleashed on the English countryside. Of course, plundering was not one-sided, on September 4, Washington included an angry rant about his own soldiers plundering local civilians, saying there would be no mercy for any offenders who were caught.

Battle of Cooch’s Bridge

Plundering aside, Howe was eager to get his army on the move. He had tried to send out scouts almost as soon as the first soldiers had landed, but torrential rain and the condition of his soldiers delayed any large movements for several days. It would be more than a week before his army began to make any significant movements.

The scouts, mostly Hessians, who did venture out found a hostile welcome. Local militia fired on a Hessian advance force at Gilpin’s Bridge. The militia destroyed the bridge and pulled back. Militia did report capturing nearly 100 prisoners and deserters as they picked off small groups of foraging parties. Some smaller groups were not captured, but simply ambushed and killed.

To assist with the harassment of the British, Washington put together a temporary regiment of 700 riflemen, one hundred pulled from each of the seven Continental brigades. He put this special force under the command of General William Maxwell. Normally, this sort of duty would have been covered by Daniel Morgan’s riflemen, but Washington had dispatched Morgan to upstate New York to assist with the defense against General Burgoyne’s northern army, still on the march at this same time. The riflemen were supplemented by another three hundred militia to occupy Iron Hill, the high ground near Cooch’s Bridge in Delaware. This was about six miles northeast of the Head of Elk, and about fifteen miles south of Washington's main encampment in Wilmington, Delaware.

|

| Battle of Cooch's Bridge (from Delaware Way) |

On September 3, Hessian jaegers approached Iron Hill. While they were still miles away, they ran into an ambush. Skirmishers on both sides engaged in a running battle back to the hill, where the bulk of Maxwell’s Continentals had entrenched themselves for a defense. About 450 jaegers approached the roughly 1000 defenders. As the two sides fired on each other, another 1300 British grenadiers and other regulars marched up to support the jaegers.

The two sides engaged in a firefight lasting most of the day, about seven hours. There is sometimes a popular myth that the British always fought in lines and did not hide behind trees or other cover as the Americans did. In truth both sides used both traditional and nontraditional tactics as the circumstances dictated. Descriptions of the jaeger assault on Iron Hill have Hessian soldiers crawling on the bellies in the underbrush as they moved forward, taking shots at the enemy when the opportunity arose.

As the battle progressed, the British brought up three cannons to use against the Continentals. The Continentals had no artillery, but were able to keep the enemy at bay with their rifles. The Americans, however, did not carry extra ammunition, and over the course of the day simply ran out of bullets.

Later in the day, General Howe had personally joined the front lines. He ordered the Hessians to storm the hill and drive off the Americans. There is an account of some fierce hand to hand fighting on the hill, although the casualty rates for the day do not seem to suggest it. The Continentals held Cooch’s Bridge until the soldiers on Iron Hill had a chance to cross. The British then stormed the bridge, driving back the Continentals. According to British reports, the Americans fled back toward Wilmington in poor order, abandoning their wounded.

Casualties for what later became known as either the Battle of Cooch’s Bridge or the Battle of Iron Hill are, as usual, much in dispute. Some British accounts list only three killed and twenty wounded. Other accounts say as many as thirty were killed and a similar number wounded. One eyewitness says ten wagons full of wounded moved back to the main British camp. American reports say they had about twenty killed and another twenty wounded. But British reports state that they buried 41 American bodies.

Whatever the exact numbers, the fighting at Cooch’s Bridge would be the only battle to take place in Delaware during the course of the war. Washington braced for a British assault in Delaware on his lines near Red Clay Creek.

Instead, General Howe gave up on his plans to meet up with the British Navy at New Castle on the Delaware River. After taking Iron Hill, Howe remained in place for several days, using the hill to reconnoiter the region. The Americans sent skirmishers to harass British outposts over the next few days but made no attempt to retake the hill.

On September 8, before dawn, the British and Hessians packed up, marched through Newark, Delaware and continued north to Hockessin. This was around Washington’s right flank. At that point, the British could have chosen to assault the Americans and push them back against the Delaware River. Howe sent a force that came within two miles of Washington’s lines, giving the impression that might be the plan.

However, Howe had no intention of attacking Washington on the ground of Washington’s choosing. Instead, Howe turned his army northwest, moving into Pennsylvania. By avoiding a battle, Howe could have simply marched miles to the west, and then north toward Philadelphia. The Continentals had no real defenses along this route.

In order to avoid this, Washington had to march his soldiers west, taking up a position along the Brandywine River. That is where the Continentals made their new plan to make a stand against the British Army.

- - -

Next Episode 158 Battle of Brandywine

Previous Episode 156 The Siege of Fort Henry

|

| Click here to donate |

|

| Click here to see my Patreon Page |

An alternative to Patreon is SubscribeStar. For anyone who has problems with Patreon, you can get the same benefits by subscribing at SubscribeStar.

Click here to go to my SubscribeStar Page

Further Reading

Websites

Virtual Marching Tour of the American Revolutionary War, The Philadelphia Campaign 1777:

https://www.ushistory.org/march/phila/elk.htm

George Weedon: https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/george-weedon

George Weedon: https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/george-weedon

Howe Declaration Aug. 27, 1777: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/rbc/rbpe/rbpe10/rbpe109/1090320a/1090320a.pdf

Delaware in the American Revolution:

https://societyofthecincinnati.org/pdf/downloads/exhibition_Delaware.pdf

Ecelbarger, Gary "George Washington's 1777 Wilmington, Delaware, Headquarters: Insights to an Unmarked Site" Journal of the American Revolution, https://allthingsliberty.com/2020/05/george-washingtons-1777-wilmington-delaware-headquarters-insights-to-an-unmarked-site

The Battle of Cooch’s Bridge: https://revolutionarywar.us/year-1777/battle-coochs-bridge

The Battle of Cooch’s Bridge: https://www.myrevolutionarywar.com/battles/770903-coochs-bridge

Letter from George Washington to Major General John Armstrong, Sr., 25 August 1777, Founders Online, National Archives https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0057

Letter from George Washington to John Hancock, 25 August 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0061

Sullivan, Thomas. “Before and after the Battle of Brandy-Wine. Extracts from the Journal of Sergeant Thomas Sullivan of H.M. Forty-Ninth Regiment of Foot.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 31, no. 4, 1907, pp. 406–418. www.jstor.org/stable/20085398

Baurmeister, Carl, et al. “Letters of Major Baurmeister during the Philadelphia Campaign, 1777-1778.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 59, no. 4, 1935, pp. 392–419. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20086940

W. H. Moomaw. “The Denouement of General Howe's Campaign of 1777.” The English Historical Review, vol. 79, no. 312, 1964, pp. 498–512. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/560990

Ecelbarger, Gary “Washington’s Head of Elk Reconnaissance: A New Letter (and an Old Receipt)”

Journal of the American Revolution, April 16, 2020: https://allthingsliberty.com/2020/04/washingtons-head-of-elk-reconnaissance-a-new-letter-and-and-old-receipt

Free eBooks

(from archive.org unless noted)

Proceedings at the unveiling of the monument at Cooch's Bridge, Historical Society of Delaware, 1902.

Hooton, Francis C.The Battle of Brandywine with its lines of battle, Wm. Stanley Ray, 1900.

Kauffman, Gerald J. and Michael R. Gallagher The British Invasion of Delaware, Aug-Sep 1777, lulu.com, 2013 (Univ. Del. website).

Reed, John Ford Campaign to Valley Forge, July 1, 1777-December 19, 1777, Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 1965 (borrow only)

Books Worth Buying

(links to Amazon.com unless otherwise noted)*

Harris, Michael C. Brandywine: A Military History of the Battle that Lost Philadelphia but Saved America, September 11, 1777, Savis Beatie, 2014.

Kauffman, Gerald J. and Michael R. Gallagher The British Invasion of Delaware, Aug-Sep 1777, lulu.com, 2013 (book recommendation of the week).

McGuire, Thomas J. The Philadelphia Campaign Vol. 1, Stackpole Books, 2006.

Mowday, Bruce September 11, 1777: Washington's Defeat at Brandywine Dooms Philadelphia, White Mane, 2002.

Reed, John Ford Campaign to Valley Forge, July 1, 1777-December 19, 1777, Pioneer Press, 1980 (orig. Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 1965).

Taaffe, Stephen R. The Philadelphia Campaign, 1777-1778, Univ. Press of Kansas, 2003

* As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

No comments:

Post a Comment