Over the last few episodes, we went through how Burgoyne’s army came down from Canada and took Fort Ticonderoga without even a fight. Many had called the fort the Gibraltar of North America because they had considered it invincible. British and German forces then chased the Americans out to Fort Ann and Hubbardton where clashes once again left the British victorious and the Americans running for their lives.

Britain Celebrates Ticonderoga

For the British, their plans seemed to be going amazingly well so far. When King George received word that Ticonderoga had fallen, he rushed to tell his wife, “I have beat them, beat all the Americans!” General Burgoyne became the toast of London, promoted to Lieutenant General and offered the Order of the Bath. For many officials and others in London, the fall of Fort Ticonderoga was supposed to be the hardest part of the campaign. All that was left was the victory march to Albany and then linking up with New York City.

|

| The Death of Jane McCrea,Vanderlyn 1804 (from Wikimedia) |

Even so, Burgoyne was optimistic. The capture of Ticonderoga would certainly be a blow to American morale. The Americans seemed to be scattering and deserting. Hopefully loyalist volunteers would turn out in greater numbers, as they had when Cornwallis took New Jersey a year earlier. Burgoyne’s local Tory advisor, Philip Skene, who had happily recovered his home at Skenesboro, assured Burgoyne that the population of upstate New York supported the King by about five to one.

Following the Battle of Hubbardton, General Burgoyne halted the British advance as he regrouped his forces at Skenesboro. This was at the bottom point where his larger ships would have to stop. Only smaller bateaux could navigate the creeks that flowed further south. Much of his army’s supplies, including most of his field artillery, were still at Fort Ticonderoga and needed to be brought to the army before they could continue.

|

| John Burgoyne (from Britannica) |

Burgoyne also considered the option of moving his army back up to Ticonderoga so that they could move down Lake George to Fort George. This would have allowed his army to have a shorter overland march to Fort Edward on the Hudson River, where the Americans were, by this time, congregating and organizing their resistance. There was also already a road between Fort George and Fort Edward, unlike the miles of wilderness between Skenesboro and Fort Edward. But Burgoyne believed that moving his entire force back north to Ticonderoga to then move down Lake George would have meant too much backtracking. Instead, he prepared his army for the overland march from Skenesborough to Fort Edward. It would take him more than two weeks to reorganize his army and collect the necessary supplies before he left Skenesboro. Once the British began moving, the column could move sometimes only a mile each day as soldiers had to cut a trail through the forest and drag cannons over mountains and across streams and swamps.

Americans in Disarray

During that same time, the American forces had scattered. General Philip Schuyler, who still had overall command of the theater for the Continentals, had already left Albany near the beginning of July to assume command at Fort Ticonderoga. When he received word that the fort had fallen, he directed the Americans to meet at Fort Edward, a small fort about fifty miles south of Fort Ticonderoga, and about 23 miles south of the British forces at Skenesboro.

It took General St. Clair nearly a week to get to Fort Edward with the 1500 men who had escaped Fort Ticonderoga and stayed with the army during the march. This, when combined with Schuyler’s army of nearly 2500, created an army of nearly 4000. Even so, that was not nearly enough to challenge Burgoyne’s army, estimated to be twice that size. Schuyler called on General Washington to send reinforcements. Washington, however, was still preparing to defend against whatever General Howe was going to do once he left New York City. He did not want to spare anyone. He only sent General Nixon from Peekskill with another 600 Continentals. He also sent Generals Benedict Arnold and Benjamin Lincoln in hopes that the popular New England officers would encourage militia volunteers to turn out.

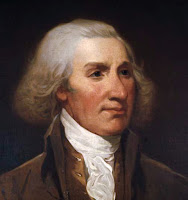

|

| Philip Schuyler (from Wikimedia) |

The militia forces were fading even faster. Thousands of militia had answered the call, but by the time of Schuyler’s July 27 letter, the General noted that of the Connecticut militia, all but seven officers and eleven men had deserted. Only 200 of 1200 militia from Berkshire County Massachusetts remained. Half of the 2100 Albany militia who had accompanied Schuyler less than a month earlier had already abandoned the army. A mere ten or twelve New Hampshire militiamen remained with the army around Fort Edward. When newly promoted General John Glover arrived in early August with a small brigade of Continentals, he described the army as “weak & shatter’d” with less than three thousand men, powerless to make a stand against an enemy advance.

Jane McCrea

The greatest source of concern for many locals was not the British or even the Germans. Those they feared most were the Indian allies. For several weeks, warriors had been all through the forest, attacking remote homes and villages, killing and scalping anyone they found. Many American soldiers wanted to be home to protect their families from such attacks. For the British, these Indian allies assured them that no Americans would be able to sneak up on them through the woods to set up an ambush. It allowed the regulars to cut a path through the wilderness without fear of attack. By July 26, General Burgoyne reached Fort Ann, about twelve miles from Fort Edward.

That evening, an Indian scouting party returned to the fort with several scalps. One of them was the long dark hair of a woman. Loyalists immediately recognized the scalp as that of Jane McCrea, a young woman in her early twenties who was the fiance of Lieutenant David Jones, an officer in the loyalist militia.

McCrea had been born in New Jersey, but had been living with her brother on a farm near Saratoga for some time. Her brothers were in the patriot militia, but as with the divisions in many families, Jane was engaged to a Tory officer. The Joneses and McCreas had been neighbors in New Jersey. The Jones family remained loyalist while the McCreas generally supported the patriots. Jane, however, still wanted the man she had known all her life and was not going to be dissuaded by the ideological differences between their families.

David Jones had fled to Quebec after being threatened for his Tory leanings. He had taken commission in a loyalist regiment and was now returning with Burgoyne’s army to retake his home for King and country. Jane had traveled north to meet up with Burgoyne’s army and reconnect with her fiance.

She had been staying at a cabin with an older woman named Sarah McNeil, who was a cousin of British General Simon Fraser. The apparent idea was that from there she would be able to get to the British Army, and reconnect with the love of her life. That was her apparent reason for remaining in this dangerous territory and away from her patriot family.

|

| Currier & Ives Print, 1846 (from Britannica) |

The Indians, who did not speak English, captured both women and were in the process of bringing them back to the British camp. They got into an argument. The details of the dispute are in question. By some accounts it was over which of them would get to keep McCrea for themselves. In other accounts, it was over which of them would collect a reward for taking her to the British camp.

As the dispute got heated, one of the warriors shot and killed the young woman. He then scalped her, stripped her, and, by some accounts, mutilated her body. The Indian accused of this act reported that she had been shot by Americans and he simply took the scalp from her dead body. But it does not appear that anyone believed that story. Jane and Sarah had been separated at the time of Jane’s death. One warrior had carried Jane away on his horse while Sarah had been forced to walk.

This was not the first Indian massacre of innocents. Since the campaign had begun weeks earlier reports from all over, as far north as the Canadian border, down to Albany, and even in western Massachusetts, Indian raids had struck, killing men, women, and children while also burning and looting property. There were also stories of rape and torture.

As bad as things got, they could have been worse. Most of the Indian raiders were a few hundred men from Canada, mostly members of the Ottawa, Wyandot, and other Algonquin tribes. The thousands of Iroquois living in upstate New York remained neutral thanks to the efforts of Indian agents sent by the Continental Congress, and through negotiation with General Schuyler. Most of the Iroquois who had joined the British were not out on their own, but were marching with Barry St. Leger’s army, a topic I’ll address in a couple of weeks. Two tribes, the Oneida and Tuscarora, which were part of the Iroquois Confederation, supported the patriots. So raiding parties, as terrifying as they were, usually remained rather small and could be defensible if the locals were organized and prepared for them.

This latest threat of Indian attacks had a long tradition going back through several wars when the French unleashed Indian allies on the colonial frontier. Older colonists had lived through these previous attacks. Younger ones had heard the horror stories.

Many frightened locals abandoned their homes and left for larger towns to stay with friends or family. In other cases, small communities all slept in one defensible home so that they could fight together if a night raid came. Farmers worked in the fields with a gun strapped to their backs. Women were left with firearms and knew how to use them. Local towns built lookout towers and used guard dogs as early warning systems against raiders. What became known as the Wilderness War of 1777 totaled dozens, if not hundreds of small raids and attacks. It is likely that patriot papers exaggerated some of the atrocities and their numbers, but there is no doubt it was happening and that Burgoyne knew about it and did nothing.

The defenses that locals had organized were not just for Indians. British and German foraging parties also had to secure food since supply lines back to Canada were becoming increasingly long and difficult. Many locals hid their food and prepared to defend whatever they had. Some foraging parties not only came back empty, but also with wagons full of casualties, the result of firefights with locals. The region was both armed and hostile to the invading army. This meant that Burgoyne relied on his Indian allies to keep the locals from organizing against the British. He could also pay for horses and other items of value that Indian raiders brought back to camp.

|

| Jane McCrea, 1912 (from JSTOR) |

Burgoyne held an inquest into McCrea’s murder. The British determined that the Wyandot had murdered McCrea and that he should be punished accordingly. Bugoyne summoned the chiefs and ordered that the murderer be given up for punishment. After considerable discussion, Indian agents warned that punishing the killer would result in a mass desertion of Indians.

In the end, Burgoyne relented on trying to punish the killer and instead ordered that a British officer accompany all raiding parties going forward.

The native warriors responded to the incident with a common response: screw you guys, I’m going home! Over the next couple of days, most of the native allies deserted the army and returned to Canada. Most of them already had more booty than they could carry. Additional restrictions and other limitations on their movements meant this was a good time as any to call it quits and return home. In addition, several loyalist officers, including McCrea’s fiancee, also attempted to resign their commissions, and when refused, also deserted.

McCrea’s death also became a rallying cry for the Americans. Newspapers up and down the continent carried exaggerated stories about her death. It played into the story that the British were unleashing savages who were killing anyone, loyalist and patriot alike, as part of the British plan to crush the spirit of the people. American General Horatio Gates would later write a letter to Burgoyne complaining about her murder, to which Burgoyne responded. The letters were published across the continent in newspapers, spreading the story of how the British unleashed savages on the Americans, killing anyone who fell into their hands. While some of these stories were certainly one sided and often exaggerated, they had the intended effect of increasing public support against the British invaders.

Meanwhile locals began hunting down Tories and native warriors in the woods and shooting them down. For years afterward people would find these bodies, left to rot where they fell. In some cases, the killers left a note attached to the body saying something to the effect of in memory of Jane Mccrea.

British Advance

About this same time, Burgoyne finally received word from General Howe in New York City. Burgoyne expected some of Howe’s army to be pushing up the Hudson Valley to meet up with Burgoyne. Instead, Howe informed Burgoyne that he intended to take his army south to take Philadelphia. Howe expected Burgoyne to defeat the Americans in New York on his own.

Despite the loss of his Indian allies, and despite the fact that Howe had apparently abandoned the northern army to fight on its own, Burgoyne pushed forward. The British found that the Americans had felled large trees and redirected creeks and rivers to make the route even more difficult. But such measures only slowed the British progress. They could not stop it.

|

| Burgoyne's March (from Rev War US) |

By July 29th Fraser’s advance force reached Fort Edward, or at least the burned out remains of where Fort Edward once stood. The Americans had completely destroyed the fort before abandoning it. They were camped about four miles further south at a place called Moses Kill. The British confirmed the American position, but were in no condition to attack until they had consolidated their forces and had time to rest.

The British had reached the Hudson River and planned to continue down river toward Albany and eventually New York City. That was the goal anyway. But reaching the river did not make marching any easier. The British could not carry their ships from Lake Champlain. They would still have to march through hostile land that was mostly wilderness.

General Burgoyne found himself in a situation that should have been more of a concern. He was mostly cut off from his supply lines. General Howe had abandoned him. He had lost most of his Indian auxiliaries. He had failed to recruit many loyalists. He faced another fifty miles of wilderness marching before he reached Albany. He had failed to capture significant prisoners or discourage the growing militia armies preparing to meet him.

Despite these concerns, Burgoyne believed that his mission was a success so far. His army was advancing and the rebels had shown no ability to stop him. He would continue his advance toward Albany.

Next week: a young and idealistic teenager arrives from France to participate in the American cause, the Marquis de Lafayette.

- - -

Next Episode 149 Lafayette in America

Previous Episode 147 Kidnapping General Prescott

|

| Click here to donate |

|

| Click here to see my Patreon Page |

An alternative to Patreon is SubscribeStar. For anyone who has problems with Patreon, you can get the same benefits by subscribing at SubscribeStar.

Click here to go to my SubscribeStar Page

Further Reading

Websites

Edgerton, Samuel Y. “The Murder of Jane McCrea: The Tragedy of an American Tableau D'Histoire.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 47, no. 4, 1965, pp. 481–492. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3048306

Engels, Jeremy, and Greg Goodale. “‘Our Battle Cry Will Be: Remember Jenny McCrea!" A Précis on the Rhetoric of Revenge.” American Quarterly, vol. 61, no. 1, 2009, pp. 93–112. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27734977

Holden, James Austin. “INFLUENCE OF DEATH OF JANE McCREA ON BURGOYNE CAMPAIGN.” Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association, vol. 12, 1913, pp. 249–310. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27734977

Stites, Karen A. “Murder Most Foul” in the North Country: The Legend of Jane McCrea

https://www.suncommunitynews.com/articles/ncl-magazine/%E2%80%9Cmurder-most-foul%E2%80%9D%C2%A0in-the-north-country-%C2%A0the-legend-of-jane-

Letter from Gates to Burgoyne re: McCrea, and Burgoyne's reply.

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1KkK2TxZRQdVQvDEvPlLiQ9xApKH6V8H3zkGLKMJs5yI

Free eBooks

(from archive.org unless noted)

Anbury, Thomas Travel through Various Parts of North America, Vol. 1, William Lane, 1789.

Bird, Harrison March To Saratoga General Burgoyne And The American Campaign 1777,

Oxford Univ. Press, 1963

Brandow, John H. The Story of Old Saratoga; the Burgoyne Campaign, to which is added New York's share in the revolution, Brandow Printing, 1919.

Clay, Steven E. Staff Ride Handbook for the Saratoga Campaign, 13 June to 8 November 1777, Combat Studies Institute Press, 2018 (US Army Website):

Digby, William The British Invasion from the North: The Campaigns of Generals Carleton and Burgoyne from Canada, Joel Munsell’s Sons, 1887.

Eelking, Max von, (translated by Stone, William L.) Memoirs of Major General Riedesel, Vol. 1, J. Munsell, 1868.

Hadden, James Hadden's Journal and Orderly Books, Joel Munsell’s Sons, 1884.

Hudleston, Francis J. Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne: Misadventures of an English General in the Revolution, Bobbs-Merrill Co. 1927.

Luzader, John Decision on the Hudson, National Park Service, 1975.

Nickerson, Hoffman The Turning Point of the Revolution; or, Burgoyne in America, (Houghton-Mifflin Co. 1928 (Hathitrust.org).

Riedesel, Friederike Charlotte Luise, Freifrau von Letters and journals relating to the war of the American Revolution, and the capture of the German troops at Saratoga, Joel Munsell, 1867.

Stone, William Leete, The Campaign of Lieut. Gen. John Burgoyne and the expedition of Lieut. Col. Barry St. Leger, Albany, NY: Joel Munsell, 1877.

Walworth, Ellen H. Battles of Saratoga, 1777; the Saratoga Monument Association, 1856-1891, Joel Munsell’s Sons, 1891.

Wilson, David The Life of Jane McCrea: With an Account of Burgoyne's Expedition in 1777, Baker, Godwin & Co. 1853.

Books Worth Buying

(links to Amazon.com unless otherwise noted)*

Furneaux, Rupert The Battle of Saratoga, Stein and Day 1971.

Ketchum, Richard M. Saratoga, Turning Point of America’s Revolutionary War, Henry Holt & Co, 1997.

Logusz, Michael O. With Musket and Tomahawk, The Saratoga Campaign and the Wilderness War of 1777, Casemate Publishing, 2010.

Luzader, John F. Saratoga: A Military History of the Decisive Campaign of the American Revolution, Casemate Publishers, 2008

Mintz, Max M. The Generals of Saratoga: John Burgoyne and Horatio Gates, Yale Univ. Press, 1990.

Taylor, Alan The Divided Ground: Indians, Settlers, and the Northern Borderland of the American Revolution, Alfred A. Knopf, 2006 (book recommendation of the week).

Troiani, Don and Schnitzer, Eric Campaign to Saratoga - 1777: The Turning Point of the Revolutionary War in Paintings, Artifacts, and Historical Narrative, Stackpole Books, 2019.

Ventor, Bruce M. The Battle of Hubbardton: The Rear Guard Action That Saved America, Arcadia Publishing, 2015.

* As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

No comments:

Post a Comment