Following Yorktown the British maintained their occupied cities in New York, Charleston, and Savannah, as well the territories that today make up Canada and Florida. They no longer planned to go on the offensive. London made clear they would not provide more soldiers for any offensive. Britain did, however, provide support to any Indian tribes who wanted to continue to fight the Americans.

One region that was still under contention was what we know today as the state of Ohio. Britain occupied a stronghold at Detroit. The Continentals held Fort Pitt. The area in between was almost entirely Indian tribes. No settlers dared try to occupy that land. When a group of French speaking frontiersmen entered the territory in 1780, with hopes of taking Detroit from the British, they were massacred by Miami Indians led by Chief Little Turtle. Those frontiersmen not killed in battle suffered slow torturous deaths and the hand of their captors (see, Episode 271).The massacre was meant to send a message to stay out of Ohio, and for the most part, it worked. White settlers largely stayed out of Ohio.

Moravians

One exception to this were the Moravians. The religious group that traces its origins back to 1400s in what is today the Czech Republic. They came to America in the early 1700’s first trying to set up communities in Georgia and the West Indies, but eventually giving up on that and focusing on Pennsylvania. They named their first two communities in Pennsylvania after the biblical town of Bethlehem and Nazareth. From there, the members spread out across several colonies.

|

| Moravian Worship |

One of their leading clergymen was David Zeisberger. Born in Moravia, in 1721, Zeisberger came to Georgia with his family at the age of six. By age 18, he was a leading force in establishing the Moravian settlement in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Several years later, the young man went to live among the Mohawk and learn their language. He learned several native languages and began to focus on a life as a missionary to the Native Americans. He received ordination as a Moravian minister in 1749 and began working and living among the Lenape (also known as the Delaware) in Pennsylvania.

By 1772, Zeisberger had established a Moravian community made up of Delaware and Munsey families. They founded a town in Ohio along the Tuscarawas River which they called New Schoenbrunn (Fine Spring). Shortly thereafter, following more immigration from Delaware families from Pennsylvania, as well as more Delaware converts from tribes already in Ohio, the Moravians established a nearby town just downriver named Gnadenhutten.

By the time the Revolution began, Zeisberger, in his fifties, was well established in Ohio Country. In early 1776 he helped to establish a third community in Ohio called Lichtenau. Zeisberger and several other missionaries established new homes there. Zeisberger and his fellow clergy, as well as the natives with whom they lived, tried to live as pacifists who would not take sides in the war. They found this increasingly hard to do as both sides demanded they become an ally or be considered an enemy.

British in Detroit

In the early part of the war, Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton, among other things, served as an Indian agent in Detroit. He convinced many of the tribes around him to support the king against the American rebels. These tribes engaged in raiding parties in Western Pennsylvania and further south in what is today Kentucky.

|

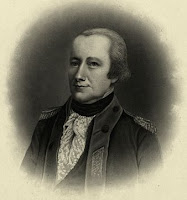

| Arent DePeyster |

As I described in an earlier episode, Virginia militia under George Rogers Clark captured Hamilton and carried him back to Virginia as a prisoner of war in 1779. After more than a year, Hamilton was paroled to British occupied New York. Once he was exchanged in 1781, he sailed for London. Although he returned to Quebec in 1782, he did not go back to take command of Detroit.

Instead, command in Detroit went to Arent Schuyler DePeyster, a loyalist from a Dutch New York family. DePeyster was a distant cousin of General Philip Schuyler, but the two men had gone in very different directions. DePeyster had received a commission the British army in 1755. During the French and Indian War he was taken prisoner and sent to France. After being exchanged, he continued to serve the British Army in Germany for the remainder of the Seven Years War. He remained a British regular, and returned to America only when his regiment was transferred to Canada. Just before the Revolution began, DePeyster became Commandant of Fort Michillmackinac in what is today Michigan. After Hamilton’s capture, Major DePeyster took command at Detroit..

As was the policy of his predecessors, DePeyster provided aid to tribes around the region of Detroit and encouraged them to attack rebel settlements to the south and east. He was known to buy prisoners from the Indians, which not only encouraged more attacks, it also encouraged the Indians to bring the prisoners back alive rather than simply killing them.

By late 1781, Detroit was holding hundreds of American prisoners. Given the poor state of Detroit’s defenses, DePeyster knew that his primary defense was primarily the hostile and active Native warriors between Detroit and the Americans in Kentucky and Pennsylvania.

Americans at Fort Pitt

The closest American base to this theater was the Continental garrison at Fort Pitt, at modern day Pittsburgh. When we last looked at Fort Pitt, Colonel Daniel Brodhead was commanding. You may recall that Brodhead grew up in eastern Pennsylvania. He was a committed patriot who received a commission as a lieutenant colonel in the Continental Army in 1776. He fought in the New York Campaign with distinction. After his regimental commander was killed, became colonel and led the 8th Pennsylvania Regiment through the Philadelphia Campaign of 1777. Following the winter at Valley Forge, Brodhead and his regiment were assigned to Fort Pitt in the summer of 1778. There, he served under several commanders. When General Lachlan McIntosh led a failed attack into the Ohio Territory in 1779, Brodhead was one of his regimental commanders. After McIntosh was recalled, Colonel Brodhead took command of Fort Pitt.

|

| Zeisberger preaching |

Shortly after his return from this campaign, Brodhead learned he was being replaced as commander of Fort Pitt. He had been accused of misuse of funds and he had to travel to Philadelphia to resolve the issue. After the matter was resolved in his favor, Brodhead returned to Fort Pitt in August. His second in command, Colonel John Gibson, had not received orders to return command to Brodhead and refused to do so. Brodhead had Gibson arrested. After a time, General Washington wrote to make clear that Brodhead did not have authority to retake command of Fort Pitt, and ordered him to return command to Gibson. At that point, Gibson had Brodhead arrested. Apparently nothing came of those charges since shortly afterward, Broadhead returned east and receive a brevet to brigadier general from General Washington

|

| William Irvine |

Irvine had grown up in what is today central Pennsylvania. He began the war as a colonel and regimental commander. His first mission was part of the Quebec campaign in early 1776. He was wounded and taken prisoner. He received parole and returned to his home in Carlisle. He would not be exchanged until the spring of 1778. He returned to service under General Anthony Wayne, and led his regiment at Monmouth. As an aside, Irvine commanded the Seventh Pennsylvania Regiment, which included Sergeant John Hays. Sergeant Hays’ wife was Mary Ludwig Hays, more commonly remembered as Molly Pitcher.

The following spring, Irvine received promotion to brigadier following the resignation of another Pennsylvania General, Thomas Mifflin. Irvine continued to serve on the Pennsylvania Line under General Wayne, but appears to have remained in New Jersey when General Wayne took much of the Pennsylvania Line to Virginia in 1781. It was around this time that Irvine received orders to go to Fort Pitt and take command of the Western Department.

So during the time of the events I’m about to discuss, Continental leadership in the west was in flux. We have the command fight between Colonels Brodhead and Gibson, then orders that Irvine is to take command, but Irvine doesn’t actually arrive at the fort until the end of this story. As a result, there was no active and unified Continental command.

The Neutral Threat

In between the British in Detroit and the Americans at Fort Pitt, the Moravians did what they could to maintain their neutrality and to let everyone know that their pacifism rendered them of no threat to anyone. Moravian leaders gladly signed agreements with the Americans that they would remain neutral. The British would not be content with their neutrality, but since they were much closer to the Americans, they hoped it would be enough.

Many other tribes were taking sides and expected their neighbors to stand by them in battle. By 1777, Moravian villages learned that many of the tribes who had allied themselves with the British would not accept neutrality. Failure to promise loyalty to Britain made one an enemy. Over the course of 1778 and 1778, most moravian communities abandoned their eastern communities and moved to the newer one further west at Lichtenau. This was farther away from either of the combatants, but much deeper into the central area of Delaware control.

Many other tribes were taking sides and expected their neighbors to stand by them in battle. By 1777, Moravian villages learned that many of the tribes who had allied themselves with the British would not accept neutrality. Failure to promise loyalty to Britain made one an enemy. Over the course of 1778 and 1778, most moravian communities abandoned their eastern communities and moved to the newer one further west at Lichtenau. This was farther away from either of the combatants, but much deeper into the central area of Delaware control.

In 1777 a group of Wyandot warriors came to Lichtenau with the intent of killing or kidnapping the Moaravian missionaries, in hopes of getting the Moravian Indians to join the war. The Moravian responded by providing a feast for the Wyandot. This seemed to appease the warriors who ended up leaving the community intact.

The Delaware chiefs signed a treaty with the Americans that promised continued neutrality, but even within the Delaware, many subgroups opposed this measure and wanted to pick a side. Many Wyandot and Mingo warriors marched through this area on the way to attack American frontier settlements. While the Moravians did not join them, they did nothing to stop them either. In fact, they regularly supplied war parties with food, shelter, and supplies, thus indirectly aiding attacks on settlements. In some instances the Moravians warned Americans of approaching war parties, but did nothing further to get involved.

Over the course of the war, many Moravians returned to their original communities at New Schoenbrunn and Gnadenhutten, where they had homes and fields. Staying away from their farms created the risk of starvation. The larger Delaware rift grew more distinct. Many Delaware moved closer to Fort Pitt in hopes of receiving American protection from pro-British war parties. Some of these warriors even joined the Continental Army.

|

| David Zeisberger |

While clearing out hostile Indians, the Brodhead party marched to the Moravian community at Salem. Knowing they were pacifists, Brodhead sent a messenger asking the Moravian leaders to come to his camp. When one of the missionaries did so, Brodhead discussed his operations and asked for the locations of Moravians so he could avoid attacking them. The missionary complied. Brodhead managed to lead a successful raid against the Delaware town of Coshocton. He also managed to steer clear of the Moravian. Some of his militia, however, were not so concerned about which Indians were a threat and which were not. Colonel Broadhead had to place his Continentals in between several Moravian villages and militia who were bent on destroying them. Thanks to Brodhead’s firm action, the militia passed over the communities.

Later that summer, a rather large war party made up of Delaware and a few other western tribes came through the region under the direction of a British officer. The group tried to force the Moravian to move to Detroit, and sought to take the missionaries by force. They managed to Capture Zeiseberger, and at least one other missionary who were taken to Detroit. These warriors did what they could to encourage the Moravian Indians to leave, They destroyed crops, livestock and looted their homes. The pacifist Indians refused to fight back. Eventually most agreed to move further west into British territory.

Since they were removed in the fall, they had no opportunity to harvest crops. Many were on the verge of starvation. Although the British had promised to provide supplies, once they got their, they found that the British only wanted to provide supplies to the families of warriors willing to join British led war parties.

A short time after the British removal, American militia under Colonel David Williamson also raided the Moravian communities, with the intent of removing them back to Fort Pitt. The Americans were surprised to find the communities largely abandoned, and only captured a handful who had avoided the British dragnet. Over the course of the winter, many hungry Moravian Indians returned to their homes, hoping to harvest and store the corn that remained ungathered in their fields. They lived in the woods near town rather than in their homes in order to avoid being captured and removed again.

The Massacre

Also during the winter months, particularly in February, the British backed warriors conducted a great many raids on the frontier settlements and houses around Fort Pitt. They would often hit isolated farmhouses, murdering families and taking scalps. In an effort to intimidate, the raiding parties would often mutilate bodies. One war party returning from a raid passed through Gnadenhutten on their return. They informed some of the Moravian Indians that they had captured a woman and a child from a farm and impaled the two on stakes on the western side of the Ohio River. They gave this information to warn the Moravians that militia would likely be headed after them in a retaliatory raid.

|

| Gnadenhutten Massacre |

On March 4, 1782, a militia force of about 160 men under the command of Colonel Williamson mustered with the intent of eliminating the Moravian villages. Fort Pitt at this time was in a state of disarray from the change in commanders. It did not approve the raid, and did not send any soldiers. The fort commander tried to send a warning to the Moravian communities, but also did nothing to stop the militia or control them.

My March 6 6h4 militia had surrounded a Moravian communities and attacked from multiple sides. The Moravian villagers did not resist, and did not run either. They believed they were neutrals and would not be harmed.

That was not the case. The first Moravian they came across was Joseph Shabosh, a man of European descent. They murdered and scalped him. Next, they came upon a group of Indians working in the cornfields. They escorted them to town, saying that they would be taken to Fort Pitt as prisoners.

The militia killed several more individuals whom they encountered, but took the larger groups into the town of Gnaddenhutten where they took away any items that could be used as weapons, bound their prisoners, and put them in two houses: one for men, the other for women and children.

The militia also took the nearby town of Salem, capturing the Indians there, and removing those prisoners back to GnadenHutten as well. The militia continued to round up Moravian families, who seemed cooperative and still being told they were being removed to Fort Pitt. The indians who remained tied up inside the two houses remained compliant, sitting bound, praying and singing Christian hymns as the militia collected more work parties still out in distant fields.

As the militia secured the Moravians, they talked among themselves about the property they had confiscated from them, including farm equipment, cooking utensils, farm implements, horses, etc. Many of the militia were convinced that the only way they could have these things would be if they had participated in raids against the settlements.

The militia held some sort of sham trial where the Moravian Indians protested their innocence and made clear they had purchased what they owned just like any other people would over many years of working and farming.

The militia determined that all of their prisoners needed to die. The men voted, only 16 or 18 voted not to kill. Realizing they were in the minority, these men left.

The remainder then got to work. The first separated out a group of prisoners they believed to be warriors. These were marched out of town and executed.

The remaining prisoners, mostly women and children had their skulls bashed in with a mallet one by one. After they were killed each body was scalped. In all 96 men women and children were executed. The militia then burned the two houses with the bodies still in them.

The primary witnesses of events were two boys who survived the massacre. One had been scalped and left for dead, but managed to hide under a pile of bodies before escaping the house after dark, and before it was set on fire. Another boy managed to hide in a cellar of the home, then escaped through a window after the house was set on fire.

Aftermath

Word spread quickly of the massacre and many returned to the village to see the remains for themselves. Zeisberger was already on his way back to Detroit by the time he received word. He hoped that most of his people had been taken back to Fort Pitt, only to learn later that all of them had been killed.

The militia returned to Pennsylvania, along with the scalps and items they had looted from their victims. At Fort Pitt, there were no consequences. General Irvine appears not to have arrived at Fort Pitt to take command until late march of 1782, several weeks after the massacre. He seemed displeased with the massacre, but did nothing about it. He needed to rely on the militia for the defense of the fort. He noted that many of the militia wanted to kill Colonel Gibson, his predecessor, for being too friendly with the Indians.

Even after the militia killed two more friendly Delaware who had sought refuge near the fort, Irving did nothing. He simply reported the matter to General Washington without any recommendation for further action. For the Continental Army, the matter was best forgotten.

Next week, we head to the West Indies where British and French fleets once again pick up the fight over island colonies.

- - -

Next Episode 310 Gnadenhutten Massacre (Available May 5, 2024)

Previous Episode 308 Congress After Yorktown

|

| Click here to donate |

|

| Click here to see my Patreon Page |

An alternative to Patreon is SubscribeStar. For anyone who has problems with Patreon, you can get the same benefits by subscribing at SubscribeStar.

| Help Support this podcast on "BuyMeACoffee.com" |

Signup for the AmRev Podcast Mail List

Further Reading

Websites

Sterner, Eric “Moravians in the Middle: The Gnadenhutten Massacre” Journal of the American Revolution, Feb. 6, 2018. https://allthingsliberty.com/2018/02/moravians-middle-gnadenhutten-massacre

“To George Washington from William Irvine, 20 April 1782,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-08209

Journal of Moravian History: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/jmorahist.12.2.issue-2

Atwood, Craig d. “The Jesus Indians of Ohio” Plough Quarterly, June 1, 2016. https://www.plough.com/en/topics/faith/witness/jesus-indians-of-ohio

Free eBooks

(from archive.org unless noted)

A true history of the massacre of ninety-six Christian Indians, at Gnadenhuetten, Ohio, March 8th, 1782, New Philadelphia: Ohio Democrat, 1870.

De Schweinitz, Edmund The Life and Times of David Zeisberger, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1870.

Fisher, Kyle David Zeisberger and the Moravian Indian Mission in the old Northwest, 1782-1808, A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Church History, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, South Hamilton, MA, 2016.

Howells, William D. Three Villages, Boston: James R. Good and Co. 1884.

Martin, Harry E. The Tents of Grace: A Tragedy, Cincinatti: Jennings and Graham, 1910.

Rau, Robert Sketch of the History of the Moravian Congregation at Gnadenhutten on the Mahoning, Transactions of the Moravian Historical Society, 1886.

Rice, William H. David Zeisberger and his Brown Brethren, Bethlehem, PA: Moravian Publication Concern, 1908.

Stocker, Harry E. A History of the Moravian Mission Among the Indians on the White River in Indiana, Bethlehem, PA: Times Publishing Co. 1917.

Zeisberger, David Diary of David Zeisberger, a Moravian Missionary Among the Indians of Ohio, Vol. 1, Vol 2, Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co. 1885.

Zeisberger, David Grammar of the Language of the Lenni Lenape or Delaware Indians, Philadelphia: James Kay 1827.

Zeisberger, David Zeisberger’s Indian Dictionary, Cambridge: John Wilson and Son, 1887.

Books Worth Buying

(links to Amazon.com unless otherwise noted)*

Brusman, Denver and Joel Stone (eds) Revolutionary Detroit: Portraits in Political and Cultural Change, 1760-1805, Detroit Historical Society, 2009 (borrow on Archive.org).

Glickstein, Don After Yorktown: The Final Struggle for American Independence, Westholme Publishing, 2015.

Olmstead, Earl P. David Zeisberger: A Life Among the Indians, Kent State Univ. Press, 1997 (borrow on Archive.org).

Olmstead, Earl P. Blackcoats Among the Delaware: David Zeisberger on the Ohio Frontier, Kent State Univ. Press, 2002.

* As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.