Recently I spoke with Andrew Roberts about his latest book on the life of King George III. Roberts is a bestselling author and well-known speaker and TV commentator. He is a Visiting Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, a Visiting Professor at the War Studies Department at King’s College, London, and the Lehrman Institute Lecturer at the New-York Historical Society. He also sits on the boards of a number of think-tanks.

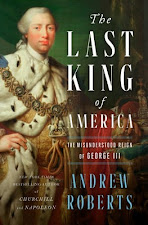

Roberts has written more than a dozen books, including biographies of Winston Churchill and Napoleon Bonaparte. He released his most recent book about King George III this year. The British release was under the title George III: The Life and Reign of Britain's Most Misunderstood Monarch. The US edition was released a few weeks later under the title The Last King of America: The Misunderstood Reign of George III.

I spoke with Dr. Roberts via Zoom in October 2021, shortly before the US release of his book about King George III.

Michael J Troy (MJT) Andrew Roberts, welcome to the American Revolution Podcast.

Andrew Roberts (AR) Thank you very much indeed, Mike. It's an honor to be on.

MJT Well, it's certainly our honor as well to have you. We're here today to discuss your new book, The Last King of America, which discusses the life of King George III. Personally, I have to say, I'm very pleased to see this book released. I've been looking for a good book that, not only covers the king, but the administration of the British government during this time period. So, the book, if anything, is a big help to me. But I wanted to ask you, why did you feel compelled to write this book?

And it struck me very strongly that, first of all, there was a huge gap in the market. I don't mind admitting I was quite cynical about this owing to the fact that there's only been one major biography of him in 50 years, and even that one was a thematic rather than a cradle to the grave life.

And secondly, I knew that there had been an awful lot of work that had been done in serious medical journals, which hadn't been picked up in the general academia, about how his mental illness was completely different from the one that we all assumed because of pictures like the madness of King George, and so on.

The third thing that came up with this was the de-stigmatization of mental illness over the last 10 years, which has been a big thing here in the United Kingdom. I know it is in America as well. And so no longer does anybody blame King George III for his mental illness. It wasn't a sort of moral failing in the way that 19th century and all too many 20th century historians made it out to be.

MJT In some ways, we in America may look at the king as - in almost in light of a parody as the evil person from whom we broke away. And of course, he's much more than that. He was a very long-serving king, almost 60 years, took Britain through a very crucial period of history.

AR I think so. And also, of course, it's perfectly understandable why Americans did have to make him out to be the cruel and despotic tyrant, not just because it's good political propaganda in a war, but also because your founding fathers were, and certainly saw themselves, as the inheritors of the mantle of the 1642 and the 1688 revolutions. That was a key part of their sense of self-worth, and understandably so. But the only drawback with that, is that you have to then make George III out to be a Stuart tyrant in the same way that the people who struggled in 1642 and 1688 did. But it was not the case, in my view at all, but a perfectly understandable, you know, human reaction.

MJT I'd like to start just briefly with George the man. Growing up, he was the first British king born in Britain in quite a few generations. George I and George II were both born and raised in Germany, spoke German primarily, took German wives. So George III was in, in many ways, a new generation of British kings. Can you speak briefly to his relationship with his father and grandfather, his grandfather and great grandfather, as well as his father who never became king?

|

| Andrew Roberts |

He fell out badly with his grandfather George II, and totally understandably so, because when his father died, George II refused to bury the body of his hated son for a fortnight, until it was literally decomposing. And poor old George III was sleeping in the room below where the putrefying corpse of his father was lying. George II also used to slap him and beat him and abuse him physically. So it's perfectly understandable that, by the time he got into his teenage years, George III really despised his grandfather, couldn't wait for him to die.

MJT That seems a lot of the relationship between George I and George II was a lot the same. There is not a love lost between that father and son. And obviously between George II, and George III 's father, as father and son never got along. And then apparently grandfather and son never got along much either.

AR And also, of course, George III, fell out with his son George IV. So this Hanovarian intergenerational hatred was a... The only people who sort of don't have it is George III and his father, Frederick, who were very close and loving. But then of course, Frederick died when George III was only 12 years old.

MJT Right? The cynic in me says, well, he never had to deal with George III as a teenager.

AR That's a very good point.

MJT But George had an interesting upbringing. In some ways. His mother reminded me in a little bit of ways of Princess Di, in that she wanted to keep him away from court and raise him separately from everything that was going on with the king and with the royal family. George was raised to be a bit of an introvert, to be somebody who was rather private, modest, simple in his life. Is that true?

AR Well, it's very true. Yes, absolutely. He didn't really have friends. And unfortunately, one of the friends he did have was Lord North. So that didn't end well either, as far as Britain is concerned, anyhow.

He was not, though, the idiot, the stupid, thick, young man and child that he's made out to be in so many biographies. You know, this is a chap who can read and write relatively early, who can write Latin, who speaks four languages, or at least understands and speaks four languages, who writes essays, very impressive, historical and constitutional essays, in his teenage years - especially once Lord Bute becomes his tutor. It's outrageous, really, the way the Whig historians, and indeed some modern American historians, still insist on him being intellectually weak. He simply wasn't.

MJT No, your book goes into great detail about a lot of his writings and especially his interest in history, and its importance in governing the country - came out very well. When I said "simple" earlier, I certainly didn't mean simple-minded. He was a man of simple tastes, though. I read somewhere else, I think, that he ate the same meal every single evening, a simple dish of mutton and vegetables.

AR Well, I'm not sure that we would have allowed that every single evening, but I do get into their diet at some stage and it's a little bit more varied than that. But he probably liked the same meal every single evening.

He dressed very soberly. He dressed as an English country gentleman, and this of course, at a time when over in France, the Bourbons at Versailles were, were dressing themselves up like Christmas trees every day.

He was frugal in his tastes. He didn't drink much alcohol. He took a lot of exercise. And he was financially prudent, certainly, unlike his son, George the fourth, who was the Imelda Marcos of the late 18th century. He had compulsive buying disorder and never asked the price of anything. At one point, his debts equal the amount that we were spending on the Royal Navy. In that sense, he has every right to continue this intergenerational strife in the Hanovarians.

MJT You report that he actually went out and just talked to people in plain clothing and they didn't even realize he was king until sometime later.

AR That's right - usually when he handed them a Guinea. That was the that was the point, which is that he probably wasn't just the normal English country gentleman.

MJT But he did seem to come across as a man of the people: thrifty, frugal, prudent, maybe the only Hanovarian and who never cheated on his wife.

AR Yeah. He loved his wife. He had a fantastic relationship with his wife, who he had married only six hours after meeting.

MJT It was an arranged marriage. She was a German princess.

AR It was entirely an arranged marriage in which he fell in love with her afterwards, and they had 15 children. It was a true love match until, of course, his malady in 1804 made it impossible because he came violence made it impossible for them to share a bed and tragically, they had to separate after that. But no, it was a true love match.

MJT You mentioned earlier, somebody who was very important in George's upbringing, John Stuart, the Earl of Bute. He was heavily criticized by the Whigs. Could you explain why that was?

AR Yes, the Whigs had essentially been in power since the 1680s, since the Great Revolution. And so both George and Bute felt that after 80 years of virtually complete oligarchic power, this sort of self-perpetuating oligarchy of Whig aristocrats, their grip on political power in in Britain needed to be broken, and other people needed to have a look in, like the Tories who looked to Lord Bollingbroke as their philosophical guide, and independents, and even Scots, like Lord Bute. Even though, of course, the Jacobite rebellion only been 15 years before the king came to the throne. So he was trying to get people from much more diverse backgrounds than the people who had ruled the country for so long. And of course, needless to say, that Whigs didn't like that one bit. And so, in a sense, you can see his reign as being 60 years, or at least 50 years before he went finally mad for the last time, of struggling against the Whig oligarchy.

MJT Maybe you could help me with this, because I've never really understood - there wasn't a strong party system in the 18th century. And the time of trying to put the Stuarts back on the throne was pretty much ended by this time. So what really was the political difference between a Whig and a Tory in the late 18th century?

AR It's a very good question. You're right. Really, the party system doesn't start until much later in the king's reign, because before that, you essentially have groups and factions around various individuals, usually great Whig aristocrats.

But there is an underlying difference in the attitude towards peace and war, the Whigs are much more pacific towards the continental commitment, the Whigs were much more pro-Hanovarian than the Tories. You know, the Tories couldn't really see why we spent a huge fortune in defending a tiny electorate, just simply because the king came from there. Or in this case, the King's great-grandfather came from there. And they looked much more to than a sort of open global Imperial Britain that was much more sort of buccaneering attitude towards the Empire and so on.

In terms of public expenditure, the Whigs were a bit more tight with money, they were concerned about money supply, and so on. So, whereas the Tories were a bit more freebooting, when it came to public expenditure if they could see an obvious advantage. But within that overall concept, there are an awful lot of individuals that would not fit into those broad categories.

MJT Right, as you said, there were no strict parties at this time, and people just tended to fall into groups where they found commonalities or had friendships or family relationships with other members of government.

George, of course, became king, near the end of the Seven Years War, about the time the French and Indian War in America ended. The Seven Years War went on for a few more years after that. He was what? About twenty years old when he became king?

AR Twenty-Two.

MJT Twenty-Two? Okay, and was married shortly after he became king to, as we said, an arranged marriage to a German Princess Charlotte, who was I think, what 16 or 17 years old at the time?

AR Yeah, yeah, very young. She was quite a feisty woman, you know. She crossed the North Sea, never having met her husband. Everybody else was seasick on the boat. She just learned English and played the harpsichord, learned how to play God Save the King, and just went straight into it. And because of her love of music, and her philanthropy and the good nature and so on, the king fell in love with that, which was not expected, frankly, and says a lot for both of them, I think,

MJT Was it primarily the king's mother who arranged the marriage, at least on the British end of things?

AR And Bute as well, and also George himself. They had a list of eight German princesses who of course, all had to be Protestant, and they basically got down to Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, because the other seven - I go into what was wrong with my book, I don't think I want to spoil it - but they managed to find seven major reasons why not to marry any of the others. So she was the bottom of the list as well. You know, nobody knew where Mecklenburg-Strelitz was. It's the size of Sussex, one of England's counties. And so, she was very much chosen, because she was a German Protestant, but then that's why the Hanovarians were on the throne in the first place.

MJT One of the things that struck me when he was going through his list of possible brides was some of the princesses may have had some commoners in their ancestry. And I think that says something to how much breeding was considered really an important thing into what made the person and that maybe having some common blood in them was going to make them a problem.

AR That's right, exactly. I mean, it's almost exactly the opposite of what we feel today. The fact that it's a jolly good thing for the royals to have a bit of non-royal blood in their veins. It's one of the reasons that Kate Middleton was welcomed so much as Prince William's bride - you know was that she didn't come from the same kind of background. So our views on all of this has completely changed, of course, in the last 250 years.

MJT So we get to the end of the French and Indian war, end of the Seven Years War, and the British government is looking to raise revenue, because they've basically doubled the national debt during the war. They've incurred a lot of expenses in America, and they start turning to some ideas about taxing the Americas: the Sugar Tax, and the Stamp Tax were two of the early ones. How much of a role did the king have in those? Or was he mostly just watching this happen?

AR He had a very little role, indeed. This was very much the government's job. The king saw his role as putting in the right person as prime minister, which he wasn't very successful at doing, frankly. They had six of them in the first seven years of his reign, and then letting them get on with it. He did not consider it his duty to be interested in sugar taxes and stamp taxes and things like that, until of course, they became that, as in the case of the Stamp Tax, the most important political issue in Britain, as well as in America.

But he certainly went along with the government's attitudes, the Grenville government's attitude, that the Stamp Act was morally justified because any of it raised was going to be spent in America, protecting Americans on the western side of the 13 colonies from the Native Americans. So he couldn't see the problem, really, with doing that. He wanted, therefore, to save the money that would otherwise be spent on raising these battalions to not be spent by the British taxpayer.

The thing that the Grenville administration was very keen on is that the Stamp Act shouldn't be too expensive. It came to about two shillings and six pencs per American per year, which spread out over the 1.9 or so million white Americans who were paying tax. It was not a hugely onerous tax, but the trouble is, it did fall on the very people who could make the loudest noise about it. Especially, there's an old story, there's an old saying that you shouldn't pick an argument with people who buy ink by the barrel. That is very much what the both the journalists...

MJT Go after the newspaper editors and lawyers. That's never a good thing.

AR Exactly, yeah. And the Stamp Act was directed primarily against lawyers and newspaper editors.

MJT I get the feeling that the king kind of set the tone: that he wanted to reduce the debt, that he wanted to bring some more balance to the economy in Britain. But yeah, he left the details up to his ministers. However, when the Stamp Tax was repealed after American protest, he seemed to think that was a bad idea.

AR He thought it was a bad idea later, but actually, at the time, he brought his own pressure to bear with the King's party to support the Rockingham Ministry in repealing the Stamp Act. At the beginning he didn't really want to, he wanted to leave it up to various members of the House of Lords like Bute, who were opposed to repeal. But when he realized he was going to lose Rockingham as prime minister, unless he did, he came over and supported the repeal of the Stamp Act.

MJT And we go through a few more taxes over the next few years, the Townsend Acts, and eventually we're left primarily with the Tea Act, which of course caused some problems. As you say, this was not an onerous tax. And in fact, the cost of tea actually went down considerably, as a result of removing some taxes that had been living in Britain, and the lack of a need to run all the tea through Britain before it reached the colonies, greatly decreased the overall price, even with the small tax left on it.

AR Well, that was the problem you see, because so many Bostonian merchants, and frankly, the Venn diagram between Bostonian merchants and smugglers has a very large shaded area between the two. And of course, they didn't want to see the price of tea, essentially halved by this great glut of East India Company tea descending on the market. So very obviously, famously took it into their own hands to do something about it.

MJT The merchants very much opposed it for self-interested reasons. But when you tie self-interest to an ideological reason, it becomes much, much, so much more. And the essential reason, of course, was this was essentially a direct tax on the colonists, or at least a tariff for purposes of fundraising, which the colonists by this time had decided was unacceptable. And so we ended up with what we call today the Boston Tea Party, the destruction of a great deal of tea in Boston, which really outraged everybody in Britain and many in the colonies as well.

AR Including the King

MJT What was the reaction in London?

AR Well, it was more shock than anything else. I mean, that the anger came later, but it was a true sense of shock that quite so much tea. I mean, it was 9,000 pounds of it - was tons of the stuff, had been thrown in the harbor. One does wonder why on earth it wasn't being protected by anyone at all, why the Sons of Liberty are able to get on those ships quite so easily and start hacking them about their hatchets. But nonetheless, there was a serious shock.

Although some of the radical weeks tried to stick up for the Sons of Liberty, they were very, very few. And overall, it was considered to be a completely outrageous overreaction, essentially by the Bostonians.

That's why the government made one of the key bad decisions in this whole period, which was, of course, to impose, what you call the Intolerable Acts, we call the Coercive Acts, the four acts that brought down such hard retaliation against Boston, or indeed Massachusetts in general.

The king was very badly advised at this time by the royal governance, including the one in Massachusetts, that basically says that Massachusetts would be left hanging basically by the other 12 provinces, and that they weren't going to stick by Massachusetts. And this was truly a dreadful piece of advice, frankly, because obviously, they did sit by them very powerfully.

MJT Interestingly, George Washington expressed annoyance and anger at the Boston Tea Party as well. He did not want to be associated with these people that were destroying property. And it really was the British reaction of imposing the Coercive Acts, which closed Boston Harbor, took away many of the rights of self-government from the people of Massachusetts, and extended the influence of Quebec in the western territories, that really turned people like George Washington who may have said, I don't want to be associated with violent protesters to turn it around and saying, Well, I can't stand these actions being taken against my fellow colonists.

AR Yes. And it's very interesting. You mentioned the western colonies, because of course, with Washington having been interested, himself, in various land deals in the Ohio Valley, which were also, back in 1763, closed down by the Proclamation. Although again, the king wasn't primarily involved in that. It was done by a member of his government, I can see you've got Ron Chernow's Life of Washington behind you there. He makes a good deal of this.

As you said earlier, when ideology and financial interests come together, it becomes a very potent mix. A better, more sympathetic Prime Minister, one thinks of William Pitt the Elder, who becomes prime minister in 1766, should have been able to have dealt with this. But unfortunately, Pitt the Elder was suffering from the most terrible gout, which almost made him go mad. And he certainly sent him into a manic depression, where he essentially was a non-existent Prime Minister for two whole years. He didn't see the king for two years. He stayed in his house in North London, and basically became a hermit, which is an extraordinary thing. absolutely disastrous, of course, for the politics of Britain and America at this time.

MJT It really seems like there were two groups of people one in the colonies, one in Britain that had a great consensus about what was happening, but the two were very different and weren't talking to each other. The Americans seem to think if we just push hard enough, like what happened with the Stamp Tax, the understanding British leadership will back down and we'll get our way. The people in Britain, I think Gage was the one who said if we act like lambs, the colonists will act like lions, whereas if we act like lions, that the colonists will act like lambs, meaning that, if we just show a little push, the colonists will immediately back down.

AR That's very much the king's view, you know, in fact, he quoted that lambs-lions line to the Prime Minister. So this was something that he very much went along with. By this stage, of course, it's Lord North. from 1770 onwards, it's Lord North. Despite being the most disastrous Prime Minister we have in British history, in over, I think it's 57 Prime Ministers we've had, he clearly was the one who comes bottom, you know. He's up there with Neville Chamberlain and Anthony Eden frankly. But at the time, he was considered a charming, intelligent, good-natured master of the House of Commons. He'd been prime minister, well he was Prime Minister for twelve years ultimately, which was an extraordinary achievement, considering that they'd had six Prime Ministers in seven years, as I mentioned. One of the interesting and fun bits about writing this book is discovering things like that, but Nord North wasn't just the complete slithering idiot. But it was actually in his heyday, domestically-speaking, at least, an extremely effective Prime Minister, that has been one of the interesting and fun things about researching this book.

MJT Yeah, there did seem to be a consensus with it. It wasn't just the king or the Prime Minister pushing this agenda. There was really a consensus among all of the leadership or most of the leadership in London that what they were doing was the right thing. And they'd seen more than a decade of violent protests in the colonies. And I think there was an idea that, well you see it in some of the writings, where they're basically referring to the colonists as over-indulged children who are now throwing temper tantrums when they don't get their way. And what they really need is a spanking.

AR You're quite right. This parents-child analogy is constantly used in the American Revolution by the Brits at least, and really stupidly so. Because America has been a colony, or some parts of at least, for 150 years. There's no sense at all of them being children. They had a longer time as a colony than as an independent state up until the year 1945. So, it's shocking that they should have been quite so, I suppose, complacent as to think of themselves as parents with recalcitrant children.

MJT Yeah, I think to continue the analogy that the British didn't understand that their children were now 18 years old, over six feet tall, and we're not going to ever be spanked.

AR Yes, absolutely. Right. That's a very, that's a very good line. I might - don't be surprised if I shamelessly plagiarize that without attribution. Mike.

MJT Go for it!

/ /

MJT Anyway, the war breaks out. The British try to show that they're going to be tough and they get basically pushed back into Boston by the New England militia and are put under siege. We're really into an all out war at this point.

Even at this point, when the war has broken out, when there's active killing on both sides, the colonists are still looking to the king to broker a political settlement. They are referring to the army in New England as the Parliamentary Army or the Ministerial Army, harkening back to the English Civil War, when there was division between the King and Parliament, with the obviously implication being that the Continental Army was really the army of the King, which of course, the King would fight absurd. But that was the kind of the argument they were making.

And I think they were hoping that, not necessarily the King had just not noticed what was going on for the last decade, but that it was giving Britain a fig leaf. It was giving Britain away out by allowing the King to be the peacemaker, and to provide the colonies with the rights that they had been fighting for all along and basically tell parliament, no, you can't do that

AR I think that's fair. But it was also an attempt wasn't it? not to so disassociate themselves from the loyalists, who made up a good third or so of the American population at the time, that they realized that they needed to bring the loyalists along. And that was a good strategy to do that. And certainly didn't want to antagonize them at that stage at least.

But what it did do was to fundamentally misunderstand the nature of the King's constitutionalism, because there was simply no way that he was going to, he evered the British Constitution and the idea that he was going to use his powers, which were very much in abeyance, really. I mean, no king, or queen had overruled and vetoed an Act of Parliament since 1708, Queen Anne. So no, he very much was not about to use his vestigial powers to help the Americans and overall his own government can't be because he was this constitutionalist and partly because he agreed with the government.

MJT Right I think what the king saw his role as doing was supporting Parliament. He wasn't going to make the mistake of Charles the First, and pick a huge fight with Parliament. So yeah, right. He was a constitutionalist. He was backing the power of Parliament. Whereas the colonists did not see the Parliament as the ruler of the British Empire. They saw the British Parliament as ruling Britain and colonial legislatures as ruling the colonies, all under the authority of the king. And that was a very different view in the way government fundamentally worked that the two did not agree on.

AR That's right. And of course, you had had well over a century, as we were saying, the American legislatures of different forms, obviously, not with any kind of democratic mandate that we'd understand today. But they were consultative bodies. They had a royal governor that did have veto powers, but tended not to want to use them.

And this is one of the things that I very much argue in this book is that it was not an oppressive tyranny. You didn't have troops on the streets, except for Boston, from 1768 onwards. You didn't have American editors being arrested, and newspapers being closed, and that kind of thing. Didn't you certainly didn't have any of the kind of apparatus of tyranny, large bureaucracies and so on, that you see all across the continent at the time, the continent of Europe, let alone the violent aggression that's shown in Prussia and Austria and certainly Russia, and by the French, in in Corsica, and the Spanish in New Orleans, where their first action really was to be as violent as possible. Yes, there's the Boston Massacre in 1770. But to a large extent, that's a riot that goes wrong. Nobody in Britain wanted to kill any Bostonians, whereas Catherine the Great killed 50,000 Russians at the time of the Pugachev uprising. So you do have a King who's very conscious of the common law, of the British constitution, and all the things that go with it.

MJT Yeah, I don't think there's any way you can argue that the government was oppressive. In fact, colonists were actually paying less taxes than people in England were.

AR Much Less. I think it was Richard Brookhiser, who has just written a very good book, saying that America in the 1760s and early 1770s was amongst the freest societies in the world. I think that's right.

MJT I think what the protesters were getting at was not that they were living under an oppressive government, but that they were slowly seeing the beginnings of changes that would make the oppressive government more oppressive a generation or two later, that they were losing their powers of self government, that they were losing. Using a lot of the things, the right of taxation, with those precedents being said, even though they were very small at the moment, they can see how those would grow very large, and they could become the next Bengal or Ireland or something like that. And that's where they didn't want to go.

AR Well, the Queen has allowed us now to look at 100,000 pages of George III's papers, correspondence, all sorts of things, abdication letter, and all that kind of thing. And there isn't a single page, in that that implies at all, that there were any plans to try to extend parliamentary or royal powers in the 1760s or indeed the 1770s.

They were reacting to the sense that the Americans, quite rightly of course, were ready for self-government. By then, you know, you didn't have any French threat. After the Treaty of Paris, any closer than Haiti, you had two and a half million population, you had a burgeoning economy. You have more bookshops in Philadelphia than in any other city of the empire, apart from London. You were ready for statehood.

And so this push towards independence and sovereignty was a perfectly understandable response. And what I like to say about this book, in particular, is that it's a very pro-American Book, really, because although yes, it does say that George was not a tyrant. Actually, if you look in history, again, and again, you see people who escaped oppressive regimes and therefore become self-governing: the Israelites with the Egyptians, the Dutch with the Spanish, the Italians with the Austrians. You name it, there's any number of examples of it: the Greeks with the Turks. But actually what the Americans did was truly exceptional, which was to become independent and sovereign in rebellion against the country that was not oppressing it. It's truly exceptional, in my view.

MJT Yeah, I guess that's true. There wasn't immediate oppression, the Americans were seeing changes taking place that they thought would lead to oppression. From the British perspective, they were saying, well, these were powers we've always had, and you're just reacting to them differently now that you're powerful enough.

AR And the Quebec Act, of course, which you refer to earlier, the idea that that was some kind of template set up to try to impose a tougher royal rule on America is frankly not true. It was in order to try and reconcile the defeated French in Canada to British rule. Yes, there were sort of issues over the borders and so on. But the fact that the King allowed the Roman Catholic French to pursue their own civil, and especially religious, liberties was not intended in any way to infringe on American ones it was just to try and calm the French which he did absolutely superbly, because we don't get any actual French uprising against British rule in Canada at all for the next 200 plus years.

MJT Right, and again, that's I think, a different viewpoint. The British saw this as being generous in offering the freedoms to the French. The American saw it as we just fought a huge French and Indian war over our right to get to those western lands and the British simply turn around and give it to the French Quebequois. So they were seeing this kind of a betrayal of what they had just fought for.

AR Yes, some of the low church. Protestants in the colonies definitely also saw it as the beginning of the sort of papalization of America. King George was portrayed by Paul Revere wearing a papal hat and this kind of thing, which absolutely... I mean, the man, it was the absolute personification of Anglicanism. He was the supreme governor of the church of England for God's sake,

MJT I think they use papal imagery as a metaphor for oppression. But yeah. So the king does come out very squarely and publicly in favor of Parliament's positions in his 1775 speech to the opening of Parliament, which pretty much kills any chance of any sort of political compromise.

AR Yeah.

MJT Actually, John Adams points out that probably that speech was the single most important factor in getting public opinion in favor of American independence.

AR That's right. And certainly George Washington felt the same way as well, that King George had done something extraordinary and outrageous, but when you read that speech, it just is absolutely part and parcel of his constitutional beliefs that he'd had ever since he was writing essays as Prince of Wales for Lord Bute in the 1750s. No, it's not a departure, as far as he was concerned, or Britain was concerned at all.

MJT For the king, there was a violent military rebellion going on, and we suppress military rebellions. That was his perspective. The American saw it as well, the king certainly not going to be our savior at this point. We're the ones doing the violent rebelling.

AR And it's also, I think, worthwhile to remember that nowhere in the world was a secessionist movement just allowed to go ahead and peacefully split off, until Norway and Sweden in 1905. I hardly need to tell an American what secessionist movements wind up doing to a country. But that was as true in 1775, as it was in 1861.

MJT Right. No government wants to give away power or land.

AR You'd be insane to start to do that. And no great empire has been given back, really, until the British in India in 1947.

MJT You go into a lot of talk in your book about the Declaration of Independence and the complaints that the colonists now raised against the King specifically. And you point out correctly, I think that the King individually wasn't responsible for many of these - that many of these have been practices that had been practiced by his grandfather and great grandfather. Many of them had been decisions made along the way. And then a lot of them were actions that were taken by his government once the fighting war had broken out.

AR That's my hope. Of the 28 charges. I only think that the ones that, charge number 17, about taxation and number 22, about Parliament's having the right of veto over American legislation are justified. However, those two charges in and of themselves do justify the American Revolution. The first third of the Declaration of Independence makes you proud to be a human being. It's the most beautiful language. It's sublime and Shakespearean. And it goes to the very heart of what liberty is all about. The next two thirds of it with its 28 charges, including some that are truly outrageous. He's accused of facilitating people being taken overseas to be tried and so on. Not a single person was taken overseas to be tried. I mean you know.

MJT They threatened to do it, but they never actually did it.

AR Yeah. And also, they have the right to do it, since Henry VIII's time. And as you say, you know, lots of this is ex post facto rationalization, explaining why you're revolting against somebody who has only done these things, because you've already revolted.

MJT Your point seems to be that we were no longer willing to be governed by Britain and Britain was acting in many of the normal processes of government to control a population.

AR Yeah, and wartime propaganda is extremely important. You've got to do it. And you think of some of the wartime propaganda that we came up with in the Second World War. It's an absolutely essential part of keeping your side together and bringing people over to you. And of course, as a result, it's entered, you know, holy writ in America almost, but I don't think that one needs necessarily to take it literally any longer, especially with regards to what it says about George III, the ad hominem attacks on on George III

MJT One of the criticisms of King George that you try to address in your book, and counter, is that he was responsible for the loss of the war.

AR Yes, when you've got such terrible generals as Howe, who veers off ignores the Germain plan, veers off to capture Philadelphia, or Burgoyne, who comes far too far down south and gets himself captured at Saratoga, or Cornwallis who comes up from Charleston, and then attaches himself into a undefensible peninsula at Yorktown. And there are various other admirals who cannot defeat the French, which is the sole job of the Royal Navy admiral. You have a prime minister also, some of the ministers, you have a prime minister like Lord North, who just hates everything to do with military matters. You've got Lord Sandwich who hates Lord Germain, the navy that think it should be a land war, and the army that think it should be a naval war. You've got to transport a third of a ton, per man, across 3000 miles. And you've also got a government back at home that doesn't want to put up taxes and won't enormously increase the armed forces necessary. And then after Saratoga, you have the French come in in February 1778. And then the next year the Spanish, next year the Dutch. The idea that this world war can be won, I think, is fanciful, and none of those things were king's fault. In fact, the poor old king - he concentrates on protecting Britain from invasion, a very real prospect of invasion in 1779.

MJT An outbreak of smallpox in the French fleet was about the only thing that saved Britain from invasion.

AR Literally the luckiest thing that happens to us in pretty much the whole of the 18th century apart from possibly the French putting their guns on the wrong side at the Battle of the Nile. That was up there too. But other than that, we thought a lot of things largely were responsible for, that poor old George III has been personally held responsible for the defeat in this war, which I don't think any serious military historian believes any longer. And so I think it's fine to say in a biography of him that this needs updating, really.

MJT I mean, I think a lot of the British strategy that was made in London made sense, especially the attempt to bring a really large army into New York and shock and awe the colonists back in, made sense. But you had General Howe, who refused to deal any sort of deathblow to the Continental Army.

AR Yeah, yeah. Incredible, landing at Kips Bay there, after a perfectly good victory at Long Island. I mean, obviously, Washington was very fortunate with the fog getting over, but on three occasions, a really fast maneuver could have trapped Washington in the coffin-like Manhattan. And he didn't,

MJT Henry Clinton had been screaming till he was blue in the face to do that, and Howe just ignored him.

AR Yeah, well, actually, Clinton also wanted to stick to the Gemain plan, where you have Burgoyne coming down from Canada, and Howe going up the Hudson and meeting at Albany - splitting off the New England colonies from the rest of the colonies. And it's, you know, it's a workable plan. It's a problem, because you need to have three armies. And you also need coordination between them, which obviously, is very difficult over essentially enemy territory.

But you also probably needed a viceroy of some kind in New York, because to change any strategy took 65 days - if you're lucky with a wind behind you, assuming that government in London was agreed on the change of strategy. So really was a very difficult war to win.

I just two days ago, debated at the National Army Museum here in London with David Petraeus. And David was saying that the war was winnable by the British. And I was pretty much arguing that it wasn't. It was the opposite way that you'd imagine that an American and a Britain would debate it. We did go through some of the terrible logistical problems that Britain had over that campaign.

MJT America really had the home field advantage. And that's I think, what won the war for them, the ability to transport across the Atlantic, and also just the size of the playing field was so big that the army could not control enough territory,

AR Well especially, exactly, especially if you adopt, as you did say, rightly, the Fabian strategy of Not Giving back unless you are on to a winner. And obviously, that didn't mean that the Americans won more of the set piece battles than than the British. They didn't. But they only fought when they wanted to. And George Washington, you know, was an absolute giant, he really was when it came to a man who could instill a sense of leadership. There's just nothing like him. And you've got other individual generals like Nathanael Greene, and I dare say, Benedict Arnold very, extremely good battlefield commanders, Clinton, who was good as a strategist, but other than that, I think you out-generaled us.

MJT Yeah, I think there are a lot of good British generals. But for me, the war was almost lost for Britain before it was won, because the Americans had done such a good job of, for lack of a better word, winning the hearts and minds of the locals, suppressing any Tory views, and encouraging enough people to support their position. The whole British position really depended on raising a loyalist army in America of colonists. And they were never able to do that because the Americans had done such a good job, before the war even began,

AR Certainly by the time of the Battle of King's Mountain, so and then with the loyalists. We were expecting when Howe. and Burgoyne. and the others went out originally to Boston, they were expecting a really significant contribution from the loyalists. And maybe the strategy of withdrawing everybody in all of the provinces back to Boston and leaving royal governors like Dunmore completely unprotected was a bad one. Because, if you had stayed in-place and tried to fight everywhere, and maybe the Loyalists would have been able to produce more help. But you're right there, of course, absolutely right. The war was lost pretty much as soon as the first shot was fired at Lexington.

MJT A lot of the British leaders, I think, got bad advice. I mean, they were told in New England, as we talked before, if you behave like lions, they'll behave like lambs, that they could come in show some force and when New England when that didn't work, they're pretty much told the same thing in the middle colonies that if you go down there, there's a lot more Tories you'll be able to take the middle colonies and isolate New England. That didn't work either. Then, after 1778, they were told, well, the southern colonies, at least, you can raise a local loyalist army and of course... I think if they had gone into, say the south very early in the war, that might have been the case, but they were always, it seemed like, a few steps too late in implementing the proper strategy.

AR Yeah, no, I very much see that. And also when Cornwallis does go north, from Charleston, he has insurgencies behind him. That's not the sort of fight and hold strategy that we know that can win insurgency campaigns,

MJT Because they couldn't raise a loyalist army. I think one British Admiral put it it was like a ship going through the sea, it can pretty much go anywhere it wants. But once it's behind the wake closes in, and it's as if it was never there.

AR That's very good analogy. Exactly. So of course, he's going to get stuck at Yorktown. Although it's his own stupid fault for getting onto a peninsula. And you don't have control of the sea. De Grasse, you know, is on his way towards you.

MJT Yeah, he was certainly hoping that the British Navy would come bail him out.

AR That is its job.

MJT It was a confluence of events that didn't work out well. So, the war ends and the king is really one of the last people to give in. I think he saw his position as being - he had to be stalwart and always calling for continued fighting and not giving up, never surrendering. Even when everybody else in the ministry had pretty much given up, the King was still saying no, we should keep going forward.

AR Yes, that's right, he and Lord Sackville, by then Lord George Germain. But then after that, of course, you do have that marvelous moment in June 1785, when John Adams comes as ambassador to London. The King says, and I've got the quote here, “I will be very frank with you. I was the last to consent to the separation, that the separation having been made, and having become inevitable, I've always said, and I say now that I will be the first to meet the friendship of the United States as an independent power.” Then, of course, 15 years later, you describe George Washington as the greatest character of the age. And he buys biographies of George Washington and things like that for his library. So, he recognizes that it was the biggest disaster for Britain since the loss of the Anjou lands in the 15th century. But equally, he is ready to try and make the best of it.

MJT I think that was good. He didn't hold a grudge.

AR Yeah, he's very unfairly treated. Because when writers say that he did hold a grudge and talks about, you know, a few bloody noses and things like that. He only actually said that when he was certifiably insane, after he'd gone mad in 1789. You can't hold the ramblings and the ravings of a person who's got bipolar disorder, and is a manic depressive against him at the time of his worst bout of it. When he was sane, he never evinced those kinds of views.

MJT The end of the world was a very difficult time for the king. I mean, not only did the war go badly, but he lost two children in the space of about two years, right at the end of the war to smallpox inoculations. He ended up getting a series of ministers that he really didn't like or trust. I think that caused a lot of stress and problems for him. Do you think that in some way contributed to his mental illness problems?

AR No, I don't think so. No, they don't seem to have been connected to politics. For example, He was under much more pressure in 1782 and 1783. And then you had that huge issue with the East India Act and dismissing the Fox-North coalition and bringing in William Pitt the Younger. If stress was going to bring on his mental illness, then that was the time but actually, he's totally fine for another five years. And then when things are relatively plain sailing, he suddenly has another severe bout of what's called the king's malady, which in this book, I hope you'll agree I completely prove was not porphyria, the disease he's always credited with, but was in fact, manic depression.

MJT Right. I think you make a very good case for that in the book, and I urge people to read it. We've covered most of the revolution, which is what we in the American Revolution Podcast care about. But of course, the King also led Britain through most of the Napoleonic Wars, and relied very heavily on Pitt the Younger for that.

AR He did. And he, of course, learned from the American Revolution, a great deal. Don't trust the loyalists is one of the things so they'd never put terribly much hope in the French royalists causing any trouble for the French revolutionary and subsequently in Napoleonic forces. They tended to try to get... they certainly got the recruitment issue under control, which it certainly wasn't at all in the time of the American Revolution. They were willing to put up taxes. They, in fact, invented income tax in order to fight the French wars. They completely changed the system whereby about buying your Commissions.

That was a very important thing that we learned from the American Revolution, and the other one was just staying in it. When the Russians fought against France for 53 months and the Prussians for 55. And the Austrians for 108 months. We the British fought the French for 242 months, as much as the rest of them put together. That was largely down to the King and Pitt opposing these various peace operations and sticking to it.

He didn't recognize Nelson and Wellington terribly well early on. But once they won a few victories, you know, he was all in favor of them getting peerages and so on. But unfortunately, the poor man was completely deranged by the time of the Battle of Waterloo. So he never knew that Waterloo had been won and the Napoleonic wars that ended

MJT The end of King George's reign is a sad one.

AR It's pathos-ridden, isn't it? Poor man, he'd gone blind and deaf, and senile and of course, he was mad as well. So he just stayed in his apartment in Windsor Castle playing the harpsichord, which he couldn't even hear. His family gave up visiting him. They never saw him. No, it's a very sad final chapter, really.

MJT His son actually was regent of Britain for the last ten years of George's life, as I understand it.

AR That's right, yeah. And carried on spending and in his monumental way that he had. When he died, he was the most unpopular monarch that Britain had ever had. And the Times actually said, No man will cry at the news that the king is dead.

MJT So yes, as I said, very interesting book, covers a lot of interesting topics related to the American Revolution, not only the king, but how his ministry was operating, what they were thinking, what leaders of Parliament were thinking at the time. I absolutely loved it. And I heartily recommend it to anyone who's interested in understanding the British side of the American Revolution.

AR Well, Mike, thank you very much indeed. And yes, there is an argument know thine enemy has always been a good, good Maxim for warfare, isn't it?

MJT Now that you've completed this book, are you working on any new projects?

AR I am, yes. I'm writing a biography of Lord Northcliffe, who was the press owner who owned 40% of the British press at the time of the outbreak of the Great War. It's a much more British than American book for obvious reasons. But nonetheless, he was a tremendously powerful figure. He made and broke governments and was a highly controversial figure. As you can imagine.

The family has very generously given me complete access to the archives that have not been used for a biography for 50 years. So there's all sorts of interesting stuff in there and I'm having a great time.

MJT Well, that sounds like an interesting project. We look forward to it. Andrew Roberts, I thank you so much for joining us on the American Revolution podcast. I appreciate your time.

AR Thank you very much indeed Mike. I've much enjoyed it.

* * *

The Last King of America: The Misunderstood Reign of George III, 2021Buy at Bookshop.

More about Andrew Roberts: https://www.andrew-roberts.net

|

| Click here to donate |

|

| Click here to see my Patreon Page |

An alternative to Patreon is SubscribeStar. For anyone who has problems with Patreon, you can get the same benefits by subscribing at SubscribeStar.

| Help Support this podcast on "BuyMeACoffee.com" |

No comments:

Post a Comment